Group Type Differences and the Dimensions of Group Cohesion

Group cohesion has four dimensions that assess how individuals feel about their role in a group socially and their role in accomplishing the group’s task (Carron et al., 2002). Arrow et al. (2000) found that groups form differently based on the forces which drive group formation. Externally driven groups generally have a task focus, while internally driven groups typically focus on the group members’ needs. Previous researchers have treated both types of groups as equivalent in their group cohesion studies (CaseyCampbell & Martens, 2009). The literature review also suggested that group tenure may play a part in group cohesion. Using an adapted version of Carron et al.’s (2002) Group Environment Questionnaire, 257 adults based in the United States shared their views about a group to which they belonged. I conducted an ANCOVA with group type as the dependent variable and group tenure as the covariate for each of Carron et al.’s (2002) four group cohesion dimensions. The results found group type did not affect the levels of Carron et al.’s group cohesion dimensions.

Keywords: group environment questionnaire, work group, club, social group

Introduction

Organizational researchers frequently study group cohesiveness. Carron et al. (2002) conceptualized group cohesion as a multi-dimensional construct, which led individuals to be attracted to groups (p. 10). Carron et al. (2002) found that group cohesion works at the individual level, with group members feeling both a social and task pull (p. 10). However, Carron et al. did not explain why different people felt attached to groups across each dimension. Arrow et al. (2008) theorized that different types of groups emerged from various forces acting on them. Those forces manifest themselves in a group’s focus on a task and personal needs. While all groups exhibit group cohesion in both task and social dimensions, Arrow et al.’s work suggested different group types may experience the dimensions of group cohesion in different ways. Conducting a quantitative study to determine if group type affects Carron et al.’s dimensions of group cohesion could inform future group cohesion research and the potential need to account for group type as researchers examine group cohesion.

Research Problem

Research on group cohesion is hindered by a lack of a standardized conceptualization of group cohesion. Many researchers developed their own definitions and measures of group cohesiveness, leading to inconsistent application across research and context. Specifically, researchers have found that group cohesion exists in social and work settings (e.g., Caperchione et al., 2011; Durneac, 2012) but have failed to distinguish if the difference in settings affects group cohesion. Instead, research has treated different types of groups as equivalent. This leads to confusion about whether different studies examine the same aspects of group cohesion and limits contextual analysis. Hence, the research problem is: Are the experiences of group cohesion distinguishable across different types of groups?

Literature Review

High group cohesion is a vital facet of group success, but group cohesion lacks a broadly accepted definition (Carless & De Paola, 2000, p. 71; Drescher et al., 2002, p. 663). Lewin’s (1943) field theory led early researchers to describe group cohesion as a uni-dimensional construct consisting of “the total field of forces that act on members to remain in the group” (Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009, p. 230). Other uni-dimensional group cohesion definitions include Spink and Carron’s (1994) definition of group cohesion as a group member’s “potential to remain in, or leave, the group” (as cited in Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009, p. 238). Carron et al. (1998) defined group cohesion as “a dynamic process that is reflected in the tendency for a group to stick together and remain united in the pursuit of its instrumental objectives and/or for the satisfaction of member affective needs” (p. 213). Casey-Campbell & Martens (2009) defined cohesion as “the group members’ inclinations to forge social bonds, resulting in the group sticking together and remaining united” (p. 223).

Later conceptual models shifted to treat group cohesion as a multi-dimensional construct. Carron and Brawley (2012) found that group cohesion operates with two distinct components: group integration and individual (p. 727). The group integration component is “the individual’s perceptions about what the group believes about its closeness, similarity, and bonding as a whole and the degree of unification of the group field” (p. 727). The individual component measures the group member’s desire to remain in the group and how they feel about belonging to the group (p. 727). Groups that more effectively meet the needs of their members have higher group cohesion (p. 727). As researchers who study group cohesion came from many backgrounds, they sometimes failed to consider how other disciplines conceptualize group cohesion (Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009, p. 224). These varied backgrounds provide a potential explanation for the lack of a consensus on a standard conceptualization of group cohesion (Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009, p. 224).

The disparate definitions of group cohesion limit researchers’ ability to study group cohesion across contexts. However, there are similar themes across the conceptualizations of group cohesion. First, a force acts on the group. The force may arise from an internal actor, or the force may come from an external actor (Carron et al., 1998, p. 213; Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009, p. 230). Second, the force holds individuals together for a purpose (Carron et al., 1998, p. 213; Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009, p. 223). However, the different definitions highlight differences in group cohesion’s operationalized conceptualizations. Researchers disagree on whether group cohesion’s forces act on the individuals within the group or the group as a whole (Keyton, 2000, p. 390). Some argue that the forces act only on the individual, and others claim it acts only on the group (Carron et al., 2002, p. 10). Other researchers argue that group cohesion’s forces act on both the individual and the group (Carron et al., 2002, p. 10).

Effects of Group Cohesion

Group cohesion is a “critical attribute” of group success (Abuke et al., 2014, p. 149). While researchers conceptualize group cohesion differently, most found it to have a positive effect on groups. Increased group cohesion led to increased group performance (Durneac, 2012, p. 38). Group members’ alignment with group objectives also comes from group cohesion (Cartwright & Zander, 1968, as cited in Abuke et al., 2014, p. 150). Group cohesion also leads to group members conforming to the group’s norms (Durneac, 2012, p. 33). Group cohesion’s task and social dimensions independently positively correlated with group performance (Casey-Campbell and Martens, 2009, p. 241). Casey-Campbell and Martens’ (2009) meta-analysis found significant group cohesion levels led to increased perceptions of a group’s effectiveness and increased task commitment (Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009, p. 227). Increased group cohesion also led to lower work-related stress levels and reduced absenteeism (Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009, p. 226).

Antecedents of Group Cohesion

Conceptualizing group cohesion as a field of forces led researchers to focus on its outcomes rather than its antecedents (Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009, p. 225). Similar to the multiple definitions of group cohesion, there is no consensus on group cohesion’s antecedents. Casey-Campbell and Martens’ (2009) meta-analysis found that one major challenge in understanding group cohesion’s antecedents was separating the definition of group cohesion from its antecedents (p. 225). Some identified antecedents of group cohesion include an individual’s intention to remain and interpersonal ties (Cartwright, 1968; Lott & Lott, 1965). Group identification and group homogeneity also appear to be antecedents of group cohesion (Hogg, 1992; van Knippenberg & Schippers, 2007).

Dimensions of Group Cohesion

While early theorists did not reach an agreement, a consensus emerged with later researchers that group cohesion is a multi-dimensional construct (Carless & De Paola, 2000, p. 72). However, researchers still tend to find that the dimensions of group cohesion align with their definition of group cohesion. For example, a researcher who viewed group cohesion as a measure of an individual’s attraction to a group found an individual’s level of attraction to the group was a significant factor in that group’s cohesiveness (Carless & De Paola, 2000, p. 73). Researchers focusing on the group as a whole found the group’s collective feelings lead to group cohesiveness (Carron et al., 2002., pp. 9-10). Additionally, interpersonal cohesion and task cohesion appears in many theorists’ group cohesion constructs (Abuke et al., 2014, p. 150).

Carron et al.’s (2002) definition of group cohesion incorporates many of the themes other researchers found. Carron et al.’s (2002) model conceptualized group cohesion as a group property measurable by the perceptions of the group’s members (p. 9). Individuals observe the group’s properties and use those observations to make decisions about the group and their desire to belong to the group (p. 9). They also examine the group’s structure and dynamics as a whole (p. 9). The group members then process their observations into social and task dimensions (p. 10).

Carron et al. (2002) also developed a validated psychometric instrument, the Group Environment Questionnaire. Carron et al.’s (2002) Group Environment Questionnaire conceptualized group cohesion as a four-construct model (p. 10). They found group integration-task addresses how individual team members felt about how the group bonded as a whole around the group’s task. Group integration-social examined how individuals felt about how the group connected as a whole socially. Individual attractions to the group-task were the individual’s feelings about her involvement in the group’s “task, productivity, and goals and objectives” (p. 10). Individual attractions to the group-social were the individual’s feelings about her level of “personal acceptance” and interactions with the group (p. 10).

Group Cohesion Differences by Type of Group

Arrow et al. (2000) developed a typology that classified group formation based on whether internal or external factors drove the group’s formation. In groups with external drivers, such as work groups, the “primary issue” is conforming to the external actor’s demands (p. 66). For groups created by internal factors, the “primary issue” is how members “coordinate and integrate their own goals, intentions, and expectations” (p. 67). Even so, according to Durneac (2012), a group should promote both the group’s task and the development of the group’s members (p. 34).

Arrow et al. (2000) defined affective integration as the emotional ties which bring people together (p. 71). Groups with internal formation drivers lead to groups with affective integration (Arrow et al., 2000, p. 71). These groups will develop shared values and suppress minority views (Arrow et al., 2008, p. 71). Ultimately those groups become part of their individual members’ “social identity” (Arrow et al., 2000, p. 72). Arrow et al.’s (2000) typology defines these groups as clubs since their primary purpose is meeting their members’ needs (p. 79). When the group meets the members’ needs, they remain in the group. When the group does not meet the members’ needs, the members leave the group. The projects accomplished by clubs serve as vehicles to meet the members’ needs (Arrow et al., 2008, p. 85).

Externally driven group formation focuses on assembling an appropriate mix of group members to accomplish the group’s tasks (Arrow et al., 2008, p. 72). In task-oriented groups, which specific individual accomplishes the task is not important, as long as they possess the appropriate skills and training to do the tasks (Arrow et al., 2008, p. 73). Arrow et al.’s (2000) typology defines these groups as work groups since their primary purpose is “completing collective projects” (p. 79).

Group members remain in groups that accomplish their reason for belonging to the group (Lawler et al., 2001, pp. 618-620). Members of task-oriented groups will remain in the group if the group is accomplishing the task, even if they do not feel strong social bonds with the other group members (Arrow et al., 2000, pp. 82-85; Lawler et al., 2001, p. 619). Similarly, a social group or club member will remain in the group if it meets their social needs (Lawler et al., 2001, p. 619). Work groups still need to provide some social support, and social groups still need to give a sense of task accomplishment, but these aspects are not the driving force behind group membership (Lawler et al., 2001, pp. 620-621). Without all types of groups providing some level of social bond and task accomplishment, the specific group will terminate (Lawler et al., 2001, p. 623).

Integrating Carron et al.’s and Arrow et al.’s Perspectives

Arrow et al.’s (2000) two types of groups, work group and club, arise from the differences in group formation and group purpose. Both group types meet group members’ task and social needs (Arrow et al., 2000). Clubs prioritize meeting members’ social needs, while work groups prioritize meeting members’ task needs (Arrow et al.). Carron et al.’s (2012) four dimensions of group cohesion differentiate how groups meet members’ task and social needs (p. 10). The four dimensions examine the social and task needs from the group members’ perspectives at the group and individual level (p. 10). Arrow et al.’s differentiation by group type suggests there may be a difference in

Carron et al.’s dimensions of group cohesion based on the type of group: work group or club.

Group Cohesion Changes Over Time

Bostrom et al. (1993, as cited in Steen et al., 2014, p. 252) found that groups’ social aspects increased over time. Arrow et al. (2000) found people in groups that met their needs were unlikely to join new groups (p. 69). When needs are unmet, individuals seek new groups to meet their needs (p. 70). If people remain in groups that meet their needs, it stands to reason group cohesion should increase over time. Some researchers found group cohesion did increase over time. For example, Oh et al. (2018) found group cohesion increased over time in experiential growth groups. Kivlighan et al. (2019) found group cohesion increased in counselor trainees as they trained together (pp. 7071). However, Steen et al. (2014) found group cohesion decreased over time (p. 250). All three of these small sample studies addressed groups that existed for a few months rather than a year or more. Additionally, all the groups studied were externally formed groups whose primary purpose was performing or learning about counseling and are therefore not a generalizable sample.

Harrison et al. (1998) found work groups with similarities in values and attitudes grew more cohesive over time (pp. 103-104). While their research was a snapshot study, it examined groups where the average tenure was four to five years, suggesting group cohesion may continue increasing beyond one year. Even though the evidence is ambiguous, group cohesion appears to increase over time, as indicated by group cohesion theory.

Theoretical Model

The literature suggests that group cohesion has both task and social dimensions, both of which operate at the individual and group levels (Carron et al., 2002). Based on how a group forms, the groups will primarily focus on task accomplishment or member development (Arrow et al., 2000). These concepts suggest groups may experience the dimensions of group cohesion differently. Groups formed by external forces — work groups — are task focused suggesting the task dimensions of group cohesion should appear more strongly than the social dimensions. Conversely, groups formed by internal forces — clubs — are focused on members’ needs suggesting the social dimensions of group cohesion should appear more strongly than the task dimensions. The literature does not indicate whether a work group or club will have greater group cohesion levels at the individual or group levels.

Time also plays a factor in group cohesion. Groups that meet their members’ task and social needs retain members and increase in group cohesion. This increased group cohesion showed in both work groups and clubs. This leads to a theoretical model of how group type leads to group cohesion. Arrow et al.’s (2000) conceptualization of group type is the independent variable and each of the four dimensions of Carron et al.’s (2002) group dimension theory are the dependent variables. Group tenure functions as a covariate.

Research Question

The probable but unestablished relationship between group type and group cohesion leads to the research question (RQ). When using a standard operationalized group cohesion model, does the group cohesion dimension vary by type of group?

Demonstrating whether the group types lead to differences in group cohesion enables researchers to proceed with more focused contextual studies. Previous studies lacked a standard operationalized model for group cohesion and therefore limited generalizability outside the group studied.

Hypotheses

As Carron et al.’s (2002) definition of group cohesion has four dimensions, it leads to four research hypotheses. Each hypothesis predicts a difference in a dimension of group cohesion based on the type of group. Each hypothesis will also have a corresponding null hypothesis that theorizes no difference in each dimension of group cohesion based on the group type. In all cases, the research hypotheses control for group tenure. The four research hypotheses appear below:

- RH1: When controlling for group tenure, there is a difference in Group Integration – Task by group type.

- RH2: When controlling for group tenure, there is a difference in Group Integration – Social by group type.

- RH3: When controlling for group tenure, there is a difference in Individual Attractions to the Group – Task by group type.

- RH4: When controlling for group tenure, there is a difference in Individual Attractions to the Group – Social group type.

Method

I conducted a convenience sample of 257 group members located in the United States using the Amazon Mechanical Turk platform.

Instrumentation

The survey respondents completed a modified version of the Group Environment Questionnaire (GEQ) developed by Carron et al. (2002) and two demographic questions. The GEQ measures Carron et al.’s four-dimensional model of group cohesion: (a) Group Integration – Task (GI-T), (b) Group Integration – Social (GI-S), (c) Individual Attractions to the Group – Task (ATG-T), and (d) Individual Attractions to the Group – Social (ATG-S) (p. 10). Respondents answered 18 questions concerning their feelings about a group they belong to (p. 17). ATG-S and GI-T each have five items, while ATG-T and GI-S have four items (p. 17). Respondents select along a 9-point Likert scale ranging from 1 – strongly disagree to 9 – strongly agree (p. 17).

Carron et al. (2002) found all of the individual dimensions of the GEQ except ATG-S had Cronbach’s alphas equal to or greater than 0.70 (p. 26). ATG-S has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.64 (p. 26). Carron et al. found the GEQ had construct and factor validity (pp. 30 & 35). They also found the GEQ a useful instrument for predicting behaviors that indicate group cohesiveness, i.e., the group remains together (p. 31). Therefore, Carron et al. determined the GEQ is a valid instrument (p. 31).

Carron et al. (2002) designed and validated the GEQ in a North American sports team context. Therefore, all the items refer to a sports team. Carron and Brawley (2012) argued the GEQ’s conceptual model could apply to other settings if certain assumptions were valid (p. 731). The assumptions for the model include: (a) the group in which cohesiveness is measured must be an actual group and not an aggregate of individuals with a shared characteristic, (b) the group members are interdependent, and (c) consider themselves part of a group (Carron & Brawley, 2012, p. 731). Carron et al. recognized researchers would like to use the GEQ outside the context of North American sports teams and provided guidance on modifying the questionnaire (pp. 3941). Minor wording changes to fit the new context generally returned acceptable results when the context still included North American participants (p. 39). Outside the North American context, the psychometric properties did not hold (p. 39). Carron et al.

recommend researchers wishing to use the GEQ in a new setting “revise the wording on any item that appears to be useful, but contains language, terminology, or a situational reference not characteristic of the group(s) under focus” (pp. 40-41). The revision requires the replacement of references to “sport” and “team” with “group” and words like “game” and “practice” with “events.” For example, “Our team is united in trying to reach its goals for performance” becomes “Our group is united in trying to reach its goals for performance.” These GEQ modifications are consistent with Carron et al.’s guidance.

The demographic questions covered the group member’s type of group and length of tenure in the group. These data items were self-reported. Arrow et al.’s (2000) work group and club definitions do not directly correspond to the English language terms’ general usage. For example, Arrow et al. (2000) defined a sports team as a work group because it is externally formed to accomplish a task (p. 85). A pilot study revealed respondents had difficulty selecting the correct group type if they were given Arrows et al.’s two group types. For example, pilot study survey respondents did not know how to correctly select the type of group for religious organizations or self-help groups.

Misclassifying the type of group would be detrimental to the purpose of this study. Instead, the group type demographic question asked the respondent to select from seven different types of groups, with a free text response option if they did not feel their group matched one of the provided options. I mapped the respondents’ selected group type to Arrow et al.’s theoretical model. The group types from the demographic questions which mapped to work group were: (a) sports team and (b) work or occupational group. The group types from the demographic questions which mapped to club were: (a) community service-oriented group, (b) political or advocacy-oriented group, (c) religious or spiritual group, (d) self-help or self-development group, and (e) social club or group. The open-ended response allowed respondents to enter a free text response for group type.

Sample

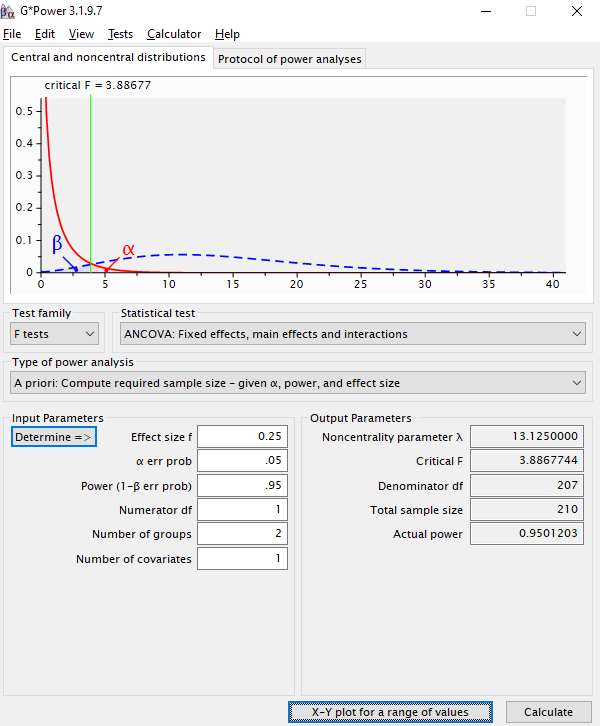

An ANCOVA design is appropriate because the research used one categorical independent variable, with one covariate, and continuous dependent variables. Faul et al. (2007) found that the G*Power 3 statistical package can determine the sample size needed in an ANCOVA design to achieve a statistical power of .95 with a 95% confidence interval. The model has one degree of freedom in the numerator, with two groups, and one covariate. Finding a medium effect required a sample size of 210, see Figure 1 (Butcher et al., 2020).

I conducted the survey using the Amazon Mechanical Turk Platform. The respondent criteria consisted of being located in the United States and having completed one previous task. The Mechanical Turk platform provided a link to the instrument and demographic questions hosted on the Survey Monkey platform. After acknowledging informed consent, the respondents completed the survey. After all the respondents completed the survey, I exported the data into Microsoft Excel to validate the data for completeness and the attention check. One survey was missing two items on a scale and was discarded for incomplete data. Thirty-one surveys failed the attention check and were discarded. Three free-text responses for group type were given. Two of the freetext responses were variations of occupational groups and mapped to work group. The third free text response was family. Arrow et al.’s (2000) theory does not provide clear guidance on considering families as clubs or work groups. This response was discarded for having an unclear group type. Of the 224 remaining valid responses, 99 respondents belonged to clubs, and 125 belonged to work groups. The minimum group tenure was one month and the maximum was 747 months, M = 62.1, SD = 70.2. The next longest tenure was 486 months.

Figure 1

G*Power 3 Inputs and Outputs Showing the Required Sample Size for the Proposed Study

Results

The study addressed how group type affects the different dimensions of Carron et al.’s (2002) model of group cohesion while controlling for tenure. The four group cohesion dimensions, ATG-S, ATG-T, GI-S, and GI-T, are the dependent variables. There was one categorical independent variable: group type. There was one metric covariate: group tenure. A one-way ANCOVA was the appropriate statistical test to examine the four hypotheses. The data were imported into SPSS Version 27 for statistical analysis. Before conducting the ANCOVA, I tested the data for the homogeneity-of-slopes assumption for each dependent variable. For each of the dependent variables, the interaction was group type with group tenure. For ATG-S the interaction was significant, F(2, 220) = 4.68, MSE = 2.18, p = .01, partial η2 = .04. For ATG-T the interaction was not significant, F(2, 220) = 2.18, MSE = 6.01, p = .12 > .05, partial η2 = .02. For GI-S the interaction was not significant, F(2, 220) = 1.60, MSE = 2.62, p = .21 > .05, partial η2 = .01. For GI-T the interaction was significant, F(2, 220) = 6.22, MSE = 1.53, p = .02, partial η2 = .05. Significant interactions mean the relationship between the dependent variable and covariate has significant differences as a function of the independent variable. This means ATG-S and GI-T failed the homogeneity-of-slopes assumption, and an ANCOVA should not be conducted for the dependent variables (Green & Salkand, 2017, p. 155). However, a visual inspection of the covariate was sufficient to establish normality with a positive skew, and an ANCOVA analysis could proceed (M. Bocarnea, personal communication, 29 October 2020). ATG-T and GI-S met the homogeneity-of-slopes assumption, and an ANCOVA was conducted.

For ATG-S, the ANCOVA was significant, F(1, 220) = 6.77, MSE = 2.20, p = .01. However, the relationship between the group type and ATG-S was very weak, with a partial η2 = .03, holding constant the length of the group tenure. Therefore, RH 1 is accepted. This means group type very weakly explained the level of ATG-S, holding group tenure constant. For ATG-T, the ANCOVA was not significant, F(1, 220) = 2.87, MSE = 6.05, p = .09 > .05. Therefore RH 2 was not supported. There was no difference in ATG-T based on group type when holding group tenure constant. For GI-S, the

ANCOVA was not significant, F(1, 220) = 1.59, MSE = 2.64, p = .21 > .05. This means RH 3 was not supported. There was no difference in GI-S based on group type when holding group tenure constant. For GI-T, the ANCOVA was not significant, F(1, 220) = 3.23, MSE = 1.55, p = .07 > .05. Therefore RH 4 was not supported. There was no difference in GI-T based on group type when holding group tenure constant.

Discussion

Carron et al. (2002) found group cohesion had four dimensions. The four dimensions addressed how group members felt about their groups, as individuals and the group as a whole, socially, and about the group’s task (Carron et al., 2002, p. 10). Arrow et al.’s (2000) work showed two major types of groups, work groups, and clubs that vary primarily in the way forces act to form the groups (Arrow et al., 2000, pp. 66-67). The two group types develop different foci in their efforts; work groups focus on fulfilling tasks, and clubs focus on the needs of the members (Arrow et al., 2000, pp. 66-67). The literature suggested the way forces organize groups, and the differing foci should affect how the groups experienced group cohesion. However, since R2, R3, and R4 were not supported and the only accepted research hypothesis, R1, accounted for 3% of the difference in ATG-S the results showed this is not the case. In addition, R1 did not meet the homogeneity-of-slopes assumption and would require additional post-hoc analysis to validate if the difference in ATG-S by group type exists.

While the findings contradict the anticipated results, they provide tangential support for previous researchers’ work to compare group cohesion across contexts (CaseyCampbell & Martins, 2009). The ability to compare group cohesion findings across contexts allows researchers to move forward with greater efficiency as group cohesion theories will not require contextual testing each time. Also, demonstrating group type does not affect group cohesion development suggests a universal process for how group cohesion develops. Many different theories for how group cohesion forms exist (Casey-Campbell & Martins, 2009). Future research may more confidently conduct experimental interventions to examine its development.

Limitations

Any use of the Mechanical Turk platform must acknowledge the potential to gather poor data (Ho et al., 2019). Ho et al. (2019) found pencil and paper and online nonMechanical Turk respondents had lower attention check failure rates or internally contradictory responses than Mechanical Turk respondents. The survey included an attention check, which resulted in 12 percent of responses being excluded from the study. Additionally, some of the retained results showed internal logical inconsistencies. For example, some respondents responded to regularly coded and reverse coded items with similar extreme values, e.g., both regular and reverse coded items scored 7, 8, or 9. While this is potentially a valid response, Carron et al.’s (2002) instrument development and validation process minimize its likelihood.

Arrow et al.’s (2002) group typology includes three subtypes for each group. Work groups can be formed for projects, specific tasks, or function as long-term teams (p. 83). Clubs can be created for economic, social, or activity reasons (p. 86). These subtypes exhibit task and social variation within their broader group classification. For example, activity clubs should show higher task focus than social clubs (pp. 87-88). The survey sample could have been overweighted with one subtype, which affected the outcome.

Recommendations for Future Research

Future research should perform a confirmatory examination of these results. The confirmatory research should also address this study’s primary limitation and avoid using the Mechanical Turk platform. Achieving similar results with a non-incentivized sample will complement the findings that there is no difference in group cohesion based on the group type.

Conclusion

The study found three of the four Carron et al.’s (2002) dimensions of group cohesion do not differ by group type. While ATG-S varied by group type, group type only accounted for 3% of group cohesion variation. This suggests group type does not have a large effect on how group cohesion forms or operates in a group. Researchers can more confidently generalize group cohesion findings across group type.

About the Author

Matthew Thrift is a Ph.D. candidate in Organizational Leadership at Regent University. He serves as an Assistant Professor at the Joint Forces Staff College in Norfolk, VA. He received his bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering from the United States Air Force Academy and his master’s degree in Aeronautical Science from Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. His interests include transformational leadership, small group dynamics, and strategic foresight. He can be contacted at mbthrift@yahoo.com.

References

Abuke, F., Wöber, K., Scott, N., & Baggio, R. (2014). Knowledge sharing in revenue management teams: Antecedents and consequences of group cohesion.

International Journal of Hospitality Management, 41(1), 149-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.05.010

Arrow, H., McGrath, J. R., & Berdahl, J. L. (2000). Small Groups as Complex Systems: Formation, Coordination, Development, and Adaptation. Sage.

Butcher, A., Erdfelder, E., Faul, F., & Long, A.G. (2020). G*Power (Version 3.1.9.7) [Computer Software]. Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf. https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower

Caperchione, C., Mummery, W. K., & Duncan, M. (2011). Investigating the relationship between leader behaviors and group cohesion within women’s walking groups. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 14(4), 325-330). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2011.03.005

Carless, S. A. & De Paola, C. (2000). The measurement of cohesion in work teams. Small Group Research, 31(1), 71-88.

Carron, A. V. & Brawley, L. (2012). Cohesion: Conceptual and measurement issues. Small Group Research, 43(6), 726-743. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/1046496412468072

Carron, A. V., Brawley, L., & Widmeyer, N. W. (2000). The measurement of cohesiveness in sports groups. In Joan L. Duda (Ed.), Advances in Sport and Exercise Psychology Measurement (2nd ed., pp. 213-226). Fitness Information Technology.

Carron, A. V., Brawley, L. R., & Windmeyer, N. W. (2002). The Group Environmental Questionnaire Test Manual. Fitness Information Technology.

Carron, A. V., Windmeyer, N. W., & Brawley, L. R. (1988). Group cohesion and individual adherence to physical activity. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10(2), 119-126).

Cartwright, D. (1968). The nature of group cohesiveness. In Cartwright, D. and Zander, A. (Eds.), Group dynamics: Research and theory (3rd ed., pp. 91–109). Harper and Row.

Casey-Campbell, M. & Martens, M. L. (2009). Sticking it all together: A critical assessment of the group cohesion-performance literature. International Journal of

Management Reviews, 11(2), 223-246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14682370.2008.00239.x

Drescher, S., Burlingame, G., & Fuhriman, A. (2012). Cohesion: An odyssey in empirical understanding. Small Group Research, 43(6), 662-689. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496412468073

Durneac, C. P. (2012). Group cohesion and performance: A bank analysis. Acta Universitatis Danubius, 8(4), 32-40.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175-191.

Green, S. B. & Salkind, N. J. (2017). Using SPSS for windows and macintosh: Analyzing and understanding the data (8th ed.). Pearson.

Harrison, D. A., Price, K. H., Bell. M. P. (1998). Beyond relational demography: Time and the effects of surface- and deep-level diversity on work group cohesion.

Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 96-107.

Ho, H., Browne, B. L., Jurs, B., Flint, E, & McCutcheon, L. E. (2019). How serious is the ‘carelessness’ problem on Mechanical Turk. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 22(5), 411-449. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/13645579.2018.1563966

Hogg, M.A. (1992). The social psychology of group cohesiveness. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Keyton, J. (2000). Introduction: The relational side of groups. Small Group Research, 31(4), 387-396.

Kivlighan III, D. M., Adams, M. C., Obrecht, A., Kim, J. Y. C., Ward, B. & Latino, C. A. (2019). Group therapy trainees’ social learning and interpersonal awareness: The role of cohesion in training groups. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 44(1), 62-76. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2018.1561777

Lawler, E. J., Thye, S. R., & Yoon, J. (2000). Emotion and group cohesion in productive exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 106(3), 616-657.

Lewin, K. (1943). Defining the field at a given time. Psychological Review, 50(3), 292-310. https://doi.org/2048/10.1037/h0062738

Lott, A.J. & Lott, B.E. (1965). Group cohesiveness as interpersonal attraction: a review of relationships with antecedents and consequent variables. Psychological Bulletin, 64(4), 269–309.

Oh, S., Mitchell, M. D., Bennett, C. M., Finnell, L. R., Saliba, Y., Heard, N. J., Pennock, E., R. (2018). Journal sharing on group cohesion and goal attainment in experiential growth groups. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 43(3), 206-229. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2018.1484541

Steen, S., Vasserman-Stokes, E., & Vannatta, R. (2014). Group cohesion in experiential growth groups. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 39(3), 236-256. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2014.924343

Van Knippenberg, D. & Schippers, M.C. (2007). Work group diversity. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 515–541.