American and Arab Cultural Lenses

Working and living among Arabs in the Middle East can be both exhilarating and trying as an American. The heat, the smells, and the sounds are enough to cause culture shock, let alone trying to figure out appropriate ways to behave and interact with the locals. Having spent over two years on the Arabian peninsula, I have experienced everything from: business shutting down in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia during prayer time; exploding bombs in Baghdad, Iraq; eating mansef goat grab with the correct (right and clean) hand in Amman, Jordan; and a most unpleasant souvenir, which I brought home in my intestines! The Middle East is an exciting place but can be very confusing to a cultural outsider. It is easy to look at things ethnocentrically and assume our way is right and others are wrong. It is important to better understand ourselves and clean our cultural lens in order to understand other’s cultural differences and nuances. This is similar to Jesus telling us to examine our own sin before we point it out in others. Jesus encouraged us to, “… first take the plank out of you own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye” (Mat 7:5, NIV).

On the surface, there seems to be a large divide between American and Arab societies. The United States is a democracy that promotes capitalism. There is a large middle class, where anyone can strive to achieve success – life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness (or property). America has a Judeo-Christian heritage. Different from this is the Middle East. Gulf Arab states are characterized by authoritarian forms of governments that include monarchies and dictatorships. The experiment of democracy in Iraq is still in its infancy. There is a wide gap between rich and poor in Arab countries. A few families control the oil and are extremely wealthy. Arab nations are predominantly Muslim (over 90%)i. With these apparent extremes, it would seem there are wide differences in culture. However, I believe common ground exists for motivating people, helping them fulfill their goals, and making them more productive. Several models are useful in exploring cultural differences and how they affect leadership. Edward T. Hall, Geert Hofstede, and the GLOBE project provide complimentary methods to analyze culture.

Edward T. Hall’s Communication and Time Dimensions

Edward T. Hall proffers two main cultural dimensions centered on communication and time. He calls these high/low-context and mono/poly-chronic.ii Table-1 defines these terms. In Beyond Culture, Hall says culture is learned, it has interrelated facets, and is shared between people groups that define their boundaries from one another.iii It is

“…what gives man his identity no matter where he is born – is his culture, the total communication framework: words, actions, postures, gestures, tones of voice, facial expressions, the way he handles time, space, and materials, and the new way he works, plays, makes love, and defends himself.”iv

Culture is a lens that gives context, structure, and meaning to how people perceive, interpret, and understand information and make sense of their world.v

Table-1

Hall’s Cultural Dimensions

| Dimension | Definition |

| High Context Communication | “…most of the information is either in the physical context or internalized in the person, while very little in the coded, explicit, transmitted part of the message.”vi |

| Low Context Communication | Information is “…vested in the explicit code”vii and the transmitted message. People in low-context cultures will seem to talk around a subject or not be specific because many things are implicitly understood and don’t need to actually be said.viii |

| Monochronic Time | “…emphasizes schedules, segmentation, and promptness…”ix Appointments are important and time is linear and compartmentalized. Monochronic people focus on one thing at a time which can deny context. Time is an asset to be used or wasted.x |

| Polychronic Time | “…stress[es] involvement of people and completion of transactions rather than adherence to strict schedules.”xi Future plans are not firm.xii |

Hall specifically aligns high-context with polychronic. According to Hall, Western European culture tends to be low-context and monochronic while Latin American, Asia, Middle Eastern, and to a lesser extent Latin European cultures tend to be high-context and polychronic. These two ways of interaction often clash; as Hall says like “oil and water”.xiii While in Saudi Arabia, two America colleagues and I were trying to get some computer equipment through customs at the airport in Riyadh. We made an appointment with the appropriate Saudi bureaucrat. We waited what seemed like an inordinate amount of time, probably only 30 minutes, while we were served tea and had to wait to see the Saudi official in his outer chambers. Once in his office, we tried to get straight to the point of why the Saudi’s would not release our computer equipment. The Saudi gentleman seemed distracted and tended to other things as we talked. He had us see other people and fill out many forms in order to get the equipment. He never would get to the point as to why we couldn’t just take our equipment. Looking back, I see that he was perhaps telling us no, without having us lose face. Eventually we did get the equipment after several more trips to the airport and paperwork. With our American low-context communication and monochronic time orientation, we could not comprehend the Saudi’s talking around the subject and from our perspective, lateness and distractedness. We could not grasp the Arab high-context and polychronic mindsets.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

Geert Hofstede consulted for IBM in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He surveyed 116,000 people in 72 different countries in 1968 and 1972. From this, he derived four different cultural dimensions, later expanded to five from another survey in 1985.xiv IBM unfortunately lost or inadvertently destroyed data on seven Middle Eastern nations (Egypt, Lebanon, Libya, Kuwait, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE).xv Hofstede retained only consolidated information from these countries and thus created his Arab World category. The five different cultural dimensions are summarized in Table-2.

Table-2

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

| Dimension | Definition |

| Power Distance (PDI) | The “…extent to which the less powerful members of institutions and organizations within a country expect and accept that power is distributed unequally.”xvi |

| Individualism vs. Collectivism (IDV) | “Individualism pertains to societies in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after himself or herself and his or her immediate family.”xvii Collectivism “…pertains to societies in which people from birth onward are integrated into strong, cohesive in-groups, which throughout people’s lifetimes continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty”.xviii |

| Masculinity vs. Femininity (MAS) | Societies are categorized as Masculine “…when emotional gender roles are clearly distinct: men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success, whereas women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with quality of life”.xix Societies are categorized as Feminine “when emotional gender roles overlap: both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with quality of life”.xx |

| Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI) | The “…extent to which members of a culture feel threatened by ambiguous or unknown situations”.xxi |

| Long-Term vs. Short- Term Orientation (LTO) | Long-Term Orientation is “…the fostering of virtues oriented towards future rewards – in particular, perseverance and thrift”.xxii Short-Term Orientation is “…the fostering of virtues related to past and present – in particular, respect for tradition, preservation of “face,” and fulfilling social obligation”.xxiii |

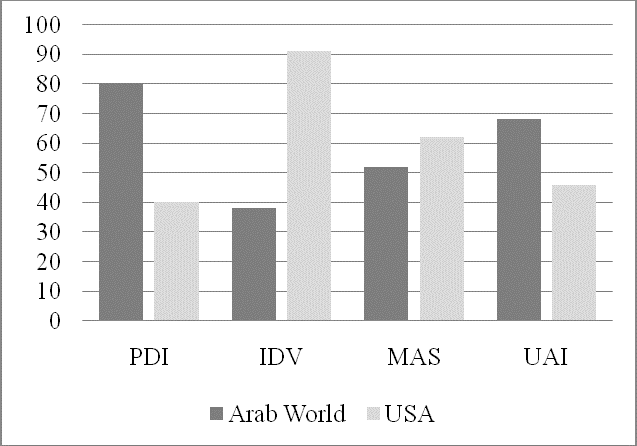

The Arab countries were not included in Hofstede’s 1985 analysis on Long and Short Term Orientation, thus only the original four dimensions are included. Figure-1 and Table-3 compare the four cultural dimensions for the Arab World and the USA. Cultural dimensions range from zero to 120. Higher numbers represent the society being more like the cultural dimension’s definition. Table-3 includes a comparison of the Arab World and the USA to mean values, rating them approximately at the mean (M), lower (L), higher (H), significantly lower (L*), and significantly higher (H*) in respective areas. Significantly higher and lower are defined as more than one standard deviation (STDEV) away from the mean to show the greater magnitude of separation and extent of the differences.

Figure-1

Arab World and USA Hofstede cultural dimensionsxxiv

Table-3

Arab World and USA Hofstede cultural dimensionsxxv

| PDI | IDV | MAS | UAI | |

| Arab World | 80 | 38 | 52 | 68 |

| USA | 40 | 91 | 62 | 46 |

| High | 104 | 91 | 110 | 112 |

| Mean | 59 | 44 | 51 | 66 |

| Low | 11 | 6 | 5 | 8 |

| STDEV | 22 | 24 | 19 | 24 |

| Arab World | H* | L | M | M |

| USA | L | H* | H | L* |

GLOBE Project Cultural Dimensions

The Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness GLOBE project is an ongoing ambitious study of culture and leadership across global cultures. It has nine cultural dimensions, summarized in Table-4, derived from an extensive survey from 1994-1997 of “…about 17,000 managers from 951 organizations…” within 62 societies.xxvi Respondents were managers in food processing, financial services, and telecommunications industries.xxvii Each cultural dimension has a value from one to seven. Higher numbers represent the society being more like the cultural dimension’s definition.

Table-4

GLOBE nine cultural dimensionsxxviii

| Dimension | Definition | |

| 1. Performance Orientation | Level at which a society values and rewards individual performance and excellence. | |

| 2. Future Orientation | Level at which a society values planning for and investing in the future, and delaying gratification. | |

| 3. Gender Egalitarianism | Level at which a society values gender equality and lessens role differences based gender. | |

| 4. Assertiveness Orientation | Level at which a society values aggressiveness, assertiveness, and confrontation. | |

| 5. Institutional Collectivism | Level at which a society values and rewards “collective action and resource distribution. | |

| 6. In-Group Collectivism | Level at which a society values cohesiveness, loyalty, and pride, in their families and organizations. | |

| 7. Power Distance | Level at which a society values stratification and concentration of power at higher levels in government and organizations. | |

| 8. Humane Orientation | Level at which a society values and rewards altruism, caring, fairness, friendliness, generosity, and kindness. | |

| 9. Uncertainty Avoidance | Level at which a society values established bureaucratic practices, norms, and rituals in order to avoid uncertainty. |

The cultural value dimensions are subdivided into values and practices. Value data comes from answers to survey questions that ask “what should be.” Practice data comes from answers to survey questions that ask “what is (or are).”xxix The GLOBE authors recognize that the idealized cultural (values) and what actually happens (practices) do not always correspond, however,

(a) values and practices both serve to differentiate between societies and organizations; (b) the values and practices each account for unique variance; (c) the values and practices scales interact; and (d) the dimension of values and practices can be meaningfully applied at both levels [societal and organizational].xxx

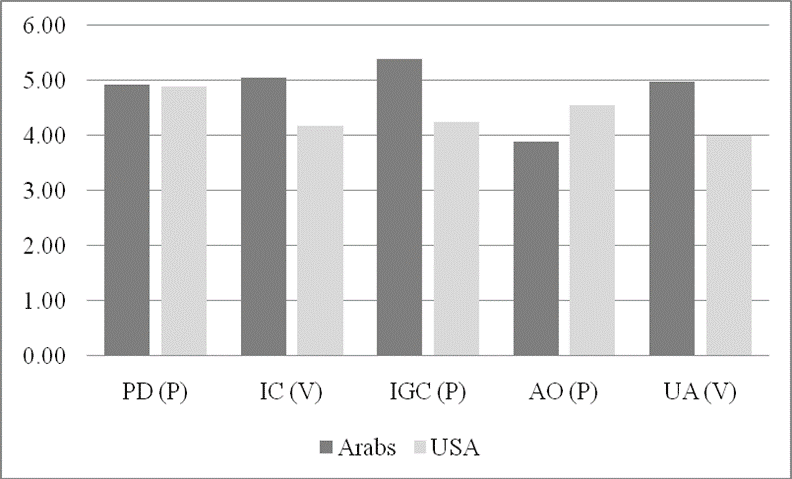

The GLOBE project studied five Middle Eastern countries (Egypt, Kuwait, Morocco, Turkey, and Qatar).xxxi Two of the countries (Egypt and Kuwait) are the same as the Hofstede Arab World countries. Both include one country from the North African Maghreb (Morocco and Libya). The GLOBE study also includes the non-Arab Turkey. For the purpose of this study, I will compare only Egypt, Kuwait, and Qatar as the closest to the Hofstede Arab World set. Using the GLOBE data, one can compare Arab (Egyptian, Kuwaiti, and Qatari) and American cultural dimensions. Figure-2 and Table-5 compare the five of nine cultural dimension practices and values that correlate to the Hofstede dimensions for the Egypt, Kuwait, and Qatar with the USA. For this comparison, I took the average of each cultural dimension between the three countries. Similar to the Hofstede dimensions in Table-2, Table-4 includes a comparison of these Arab countries and the USA to mean values, rating them approximately at the mean (M), lower (L), higher (H), significantly lower (L*), and significantly higher (H*) in respective areas.

Figure-2

Arab and American GLOBE cultural dimensionsxxxii

Table-5

Arab and American GLOBE cultural dimensions xxxiii

| PD (P) | IC (V) | IGC (P) | AO (P) | UA (V) | |

| Arab | 4.92 | 5.04 | 5.38 | 3.88 | 4.98 |

| USA | 4.88 | 4.17 | 4.25 | 4.55 | 4.00 |

| Mean | 5.17 | 4.73 | 5.13 | 4.14 | 4.62 |

| Low | 3.89 | 3.83 | 3.25 | 3.38 | 3.16 |

| High | 5.80 | 5.65 | 6.36 | 4.89 | 5.61 |

| STDEV | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.73 | 0.37 | 0.61 |

| Arab | L | H | H | L | H |

| USA | L | L | L* | H* | L* |

Figure 2 and Table 5 yield similar results to the Hofstede dimensions. The USA is on the high side and the Arab countries on the low side of Assertiveness Orientation (AO) practice. The Arab countries are on the high side and the USA on the low side of Power Distance (PD) practice, Individual Collectivism (IC) value, In- Group Collectivism (IGC) practice, Uncertainty Avoidance (UA) value. Americans value aggressiveness, assertiveness, and confrontation more than the Arabs who have a lower AO score.

Comparisons between Hofstede and GLOBE

There is much debate on the appropriateness and validity of Hofstede’s and the GLOBE project’s cultural value dimensions. In their seminal work; Culture, Leadership, and Organizations; House et al. comment on the correlation between their and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions.xxxiv Hofstede believes that values differentiate societies and practices differentiate organizations. But he then mixes both in his cultural dimensions and doesn’t distinguish between societies and organizations.xxxv The GLOBE authors say that values and practices can exist at both the societal and organizational level.xxxvi This can cause some confusion when comparing the two. The GLOBE authors analyzed Hofstede’s original four dimensions and found that Individualism and Masculinity seem to be related more to values. Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance are mixed. The GLOBE authors further discovered that Hofstede’s Power Distance dimension is positively correlated with their Power Distance practice and Hofstede’s Uncertainty Avoidance is positively correlated with their Uncertainty Avoidance value.xxxvii The GLOBE authors use two dimensions (Institutional Collectivism and In-Group Collectivism) that cover aspects of Hofstede’s Individualism dimension. Hofstede’s Individualism is negatively correlated to GLOBE’s Institutional Collectivism value dimension and In-Group Collectivism practice dimension.xxxviii The GLOBE authors also use two dimensions (Gender Egalitarianism and Assertiveness) that cover aspects of Hofstede’s Masculinity dimension. Hofstede’s Masculinity is positively correlated to GLOBE’s Assertiveness practice dimension.xxxix Gender Egalitarianism was not however correlated to Hofstede’s Masculinity dimension. GLOBE’s Performance, Future, and Humane Orientations are not directly correlated to Hofstede’s cultural dimensions.

The November, 2006 issue of the Journal of International Business Studies contains an interesting exchange and debate between Hofstede and the GLOBE authors (Javidan et al.) regarding the veracity of their models.xl Both sides take issue with the other’s methodology. Hofstede complains about the GLOBE project only surveying managers, making distinctions between values and practices, and having too many dimensions to be useful.xli Javidan et al. defend their more complex model and point to its more thorough empirical research.xlii Cross-cultural organizational psychologist, Peter B. Smith, points out strengths and weaknesses of both models and questions how many cultural dimensions are necessary and useful in understanding other cultures. He argues that individualism/collectivism and power distance are the most common dimension studied by others.xliii P. Christopher Early, another expert in cross-cultural organizational psychology, concurs with Smith and argues that the GLOBE study is perhaps too wieldy and scholars should focus on studying and understanding smaller cultural groups as opposed to making overarching models.xliv I tend to agree that fewer dimensions are generally easier to grasp.

Interpreting Common Cultural Dimensions

Using just four cultural dimensions, here labeled: Power Distance (PDI and PD), Individualism/Collectivism (IDV and IC/IGC), Assertiveness (MAS and AO), and Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI and UA); yields the following analysis. Americans rate as one of the highest of any country in the area of Individualism. Arabs tend to be more Collectivistic. As an individualistic culture, Americans value completion and reward personal performance. Arabs on the other hand, value teamwork and collaboration more. They are less likely to act independently or allow themselves to stand out from others. Thinking back to my times working with the Jordanian military reinforces this point. Everything was very group oriented; the meetings, the planning sessions, the decision making, and even the social festivities after work. We had big feasts with our Jordanian hosts, to include the mansef and drinking smoke, as they say, through hookah pipes.

The USA rates higher in Assertiveness than the Arabs. Americans are more assertive, tough, and task oriented, while Arabs are more modest, tender, and concerned with relationships. Similar to my American low- context communication and monochronic time vs. the Arab high-context and polychronic orientations, I experienced the differences in assertiveness dealing with the Saudi airport official. We were very direct and to the point about getting our computer equipment. The Saudi gentleman was more concerned with getting to know us and tending to other people.

Arabs rate higher than the USA in the area of Power Distance. Arabs respect positions of power and people in authority more than in the USA. There is more formality between leaders and followers. Arab leaders are expected to have privileges that others may not. Leaders are seen as knowledgeable and strong and are depended on to make decisions. I collect coins and found a shop in the souk in Doha, Qatar that sold foreign coins. They even had a pack of US coins with a penny, nickel, dime, and quarter. The listed price was about $5 equivalent! I figured if the pack of US coins wasn’t worth $5, then the packs of other foreign coins were not either. I had several US coins in my pocket to include various state quarters. I asked the clerk in the area of the store if I could trade some of my quarters for some foreign coins. He said he had to get his supervisor. Another man came over and I explained the experienced once again that I would like to exchange my US quarters for some foreign coins. He disappeared for a while and returned to say that we must go see the store owner. We went upstairs in the building and I entered an office with three older Arab men. I believe the first two gentlemen were from South Asia, perhaps Pakistan. I explained for a third time that I wanted to trade US quarters for foreign coins. The owner said he was a coin collector too and had a number of US state quarters. We eventually made a deal and I traded some US quarters for several packs of foreign coins. As an American, I did not understand high power distance. I understood that maybe the clerk couldn’t make a deal but was surprised when his supervisor had to defer to the store owner to make a decision. In my US culture, I was more accustomed to managers empowered to make decisions.

Perhaps less risk-adverse than Americans, Arabs rate higher in Uncertainty Avoidance. Entrepreneurship and innovation seem to be valued less than maintaining the status quo. Maintaining tradition is more important than change. Although I know that Arabs are very concerned about holding onto their cultural and religious traditions, this doesn’t mean that they are not very shrewd shop owners and entrepreneurs. These cultural dimensions coupled with personal and societal experience, create what anthropologist and sociologist, Glen Fisher calls a cultural mindset that is used as a lens through which people view events and each other.xlv Table-6 depicts America and Arab lenses with the combined Hofstede/GLOBE and Hall cultural dimensions.

Table-6

America and Arab Cultural Lenses

| American | Arab | |

| Individualism/Collectivism | Individualistic | Collectivistic |

| Assertiveness | High | Low |

| Power Distance | Low | High |

| Uncertainty Avoidance | Low | High |

| Communication Context | Low | High |

| Time Orientation | Monochronic | Polychronic |

Conclusion

In order to communicate, work, and live with people in other cultures, it is important to understand one’s own ethnocentric lens before one can begin to interpret others. Hall, Hofstede, and the GLOBE project authors provide useful dimensions to compare and better understand the differences. These cultural dimension models are helpful for making broad generalizations. Yet I have met many Americans that fit the Arab cultural profile; thus the challenge of broad categories. French sociologist, Raymond Boudon advises, “…try to find the simple reasons behind the individual actions before sketching more complicated conjectures.”xlvi Therefore it is paramount to get to know people as individuals and not stereotype them based on these one-size-fits-all models. Doing this is a great way to open communication as Jesus commissions us to be His, “…witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth” (Acts 1:8, NIV). Christians are called to share the Gospel in their city, country, national, and globally. Making a commitment to continue learning about Arab culture is important for Americans that wish to live, work, and ultimately fulfill the Great Commission in the Middle East.

About the author

Fredric W. Rohm, Jr. retired from the Army as a Lieutenant Colonel on 1 November 2007. During his 20-year career, he served in Infantry, Ordnance, and Psychological Operations branches. His last job on active duty was with U.S. Special Operations Command. He spent a year and a half total time in several Middle East countries: Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. Currently, he is an Assistant Professor and the MBA Program Coordinator at Southeastern University in Lakeland, Florida. He holds a BS in Mathematics from Penn State University, an MBA from Hawaii Pacific University, an MS in International Relations from Troy University, and is currently a Ph.D. student in Organizational Leadership at Regent University.

Notes

i http://www.state.gov/p/nea/ci/index.htm.

ii Edward T. Hall (1914-2009) was a pioneering anthropologist in cross-cultural communication (http://www.edwardthall.com).

iii Edward T. Hall, Beyond Culture (New York, NY: Anchor Books, 1976): 16.

iv Ibid, 42.

v Ibid, 85-88.

vi Ibid, 91

vii Ibid

viii Ibid, 91, 101, 113.

ix Ibid, 17.

x Ibid, 18-19.

xi Ibid, 17.

xii Ibid, 19.

xiii Ibid, 91, 150.

xiv Geert Hofstede, Culture’s Consequences, Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations (2nd ed.) (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001), xix and 351.

xv Ibid, 52. This data came from a total of 141 respondents 79 in 1969 and 62 in 1972.

xvi Ibid, 46.

xvii Ibid, 76.

xviii Ibid.

xix Ibid, 120.

xx Ibid.

xxi Ibid, 167.

xxii Ibid, 210.

xxiii Ibid.

xxiv Derived from: Geert Hofstede, Culture’s Consequences, Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations (2nd ed.) (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2001).

xxv Ibid.

xxvi Robert. J. House, Paul J. Hanes, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, & Vipin Gupta, Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: the GLOBE Study of 62 Societies (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004), 3.

xxvii Geert Hofstede, “What did GLOBE really measure? Researchers’ minds versus respondents’ minds.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6, (2006, November 1): 882-896, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.regent.edu.

xxviii Robert. J. House, Paul J. Hanes, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, & Vipin Gupta, Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: the GLOBE Study of 62 Societies (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004), 11-13

xxix Ibid, 16.

xxx Ibid, 75.

xxxi Robert. J. House, Paul J. Hanes, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, & Vipin Gupta, Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: the GLOBE Study of 62 Societies (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004), 190.

xxxii Derived from: Robert. J. House, Paul J. Hanes, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, & Vipin Gupta, Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: the GLOBE Study of 62 Societies (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2004).

xxxiii Ibid.

xxxiv Ibid, 138-41.

xxxv Ibid, 75.

xxxvi Ibid.

xxxvii Ibid, 139-140.

xxxviii Ibid.

xl Geert Hofstede, “What did GLOBE really measure? Researchers’ minds versus respondents’ minds.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6, (2006, November 1): 882-896, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.regent.edu. and

Mansour Javidan, Robert J. House, Peter W. Dorfman, Paul J. Hanges, and Mary Sully de Luque, “Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: a comparative review of GLOBE’s and Hofstede’s approaches.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6, (2006, November 1): 897-914, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.regent.edu.

xli Geert Hofstede, “What did GLOBE really measure? Researchers’ minds versus respondents’ minds.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6, (2006, November 1): 882-896, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.regent.edu.

xlii Mansour Javidan, Robert J. House, Peter W. Dorfman, Paul J. Hanges, and Mary Sully de Luque, “Conceptualizing and measuring

cultures and their consequences: a comparative review of GLOBE’s and Hofstede’s approaches.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6, (2006, November 1): 897-914, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.regent.edu.

xliii Peter B. Smith, “When elephants fight, the grass gets trampled: the GLOBE and Hofstede projects.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6, (2006, November 1): 915-921, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.regent.edu.

xliv P. Christopher Earley, “Leading cultural research in the future: a matter of paradigms and taste.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6, (2006, November 1): 922-931, http://0-www.proquest.com.library.regent.edu.

xlv Glen Fisher, Mindsets, The Role of Culture and Perception in International Relations (2nd ed.) (Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press, 1997).

xlvi Raymond Boudon, The Origin of Values: Sociology and Philosophy of Beliefs (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2001).

References

Department of State Country Notes.

Earley, P. Christopher. 2006. “Leading cultural research in the future: a matter of paradigms and taste.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6, (November 1): 922-931.

Fisher, Glen. 1997. Mindsets, The Role of Culture and Perception in International Relations (2nd ed.). Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Guideline for the use of GLOBE cultural and leadership scales (2006, August 1). Glendale, AZ: Thunderbird School of Global Management.

Hall, Edward T. 1976. Beyond Culture. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture’s Consequences, Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, Geert. 2006. “What did GLOBE really measure? Researchers’ minds versus respondents’ minds.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6,

(November 1): 882-896. Hofstede, Geert & Gert J. Hofstede. 2005. Cultures and Organizations, Software of the Mind. New York, NY. McGraw Hill.

House, Robert. J., Paul J. Hanes, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, & Vipin Gupta. 2004. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: the GLOBE Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Javidan, Mansour, Robert J. House, Peter W. Dorfman, Paul J. Hanges, and Mary Sully de Luque. 2006. “Conceptualizing and measuring cultures and their consequences: a comparative review of GLOBE’s and Hofstede’s approaches.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6, (November 1): 897-914.

Boudon, Raymond. 2001. The Origin of Values: Sociology and Philosophy of Beliefs. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Smith, Peter B. 2006. “When elephants fight, the grass gets trampled: the GLOBE and Hofstede projects.” Journal of International Business Studies 37, no. 6, (November 1): 915-921.