Effects of Servant Leadership on Satisfaction with Leaders: Inclusion of Situational Variables

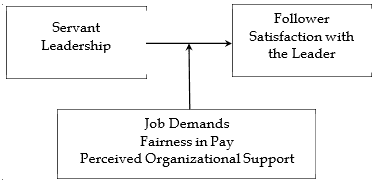

This paper presents a research study exploring whether the effects of servant leadership on follower satisfaction with the leader can be moderated by some situational variables. It builds a model constituting of five theories, namely servant leadership as the independent variable, satisfaction with the leader as the criterion variable, job demands, fairness in pay and perceived organizational support as situational variables. It employs a cross-sectional survey from a combination of five questionnaires pertaining respectively to each variable under investigation to collect data from 123 employees working in five small organizations in northern Haiti. Using regression analysis, the results indicate that only the first hypothesis is supported and that none of the situational variables yield significant moderating effects. The paper explains what may cause such results and suggests further investigators test the model with leader-member exchange relationship as a situational variable.

Follower satisfaction with the leader is vital to organizational success (Scarpello & Vandenberg, 1987). Such satisfaction is contingent upon several factors among which figure the relationship between the leader and the follower (Graen & Cashman, 1970) and the assumptions the latter makes about the former (Eden & Leviatan, 1975). These assumptions are part of and explained by implicit leadership theories that are beliefs and suppositions followers hold about the characteristics of good and effective leaders (Eden & Leviatan, 1975). Followers logically and naturally show satisfaction with leaders who are perceived to be good and effective (Yukl, 2010). (It has been shown) they use performance, actions and intentions to judge leaders’ goodness and effectiveness (Yukl, 2010). Leaders that make service their primary goal, who seem to show unconditional dedication, who appear to be highly concerned about followers and seek to empower subordinates are more likely to benefit from the latter’s approval and appreciation (Yukl, 2010). Such leaders are called in leadership literature servant leaders (Greenleaf, 1977). The question is: will the effects of servant leadership on followers’ satisfaction with the leader remain the same when the work is demanding? Additionally, will employees’ satisfaction with leaders who appear to be servants be positive and higher when the former believe they are paid with fairness and perceive they work in an organization that supports them?

The starting point for the present research is the concept that when employees perceive that their leaders exhibit integrity and concern about them, they are more likely to trust such leaders, to like them, and consequently to show satisfaction with them (Yukl, 2010). However, some situational aspects of the job may have the potential to moderate followers’ satisfaction in the sense that they can increase or decrease it (Ivancevich, Konopaske, & Matteson, 2008). Employee satisfaction with the leader can be decreased by the pressure of the work (Panatika, O’Driscollb, & Anderson, 2011) and increased with perceived fairness in pay (Wu & Wang, 2008) and organizational support (Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997). A pattern for explaining these phenomena is provided by the following five leadership theories: (a) Servant Leadership (Greenleaf, 1977), (b) Follower satisfaction with the leader (Scarpello & Vandenberg, 1987; Yukl, 2010), (c) Job Demands (Karasek, 1979), (d) Fairness in Pay (Heneman & Schwab, 1985), and (e) Perceived Organizational Support (Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchinson, & Sowa, 1986). This model in figure 1 is new in that it explores the effects of servant leadership theory on follower satisfaction with the leader while moderating such effects by situational aspects of the work environment such as job demands, fairness in pay and the organization support to employees.

Literature Review

This section reviews the literature pertaining to the model. It provides the theoretical explanation for it, and additionally presents the logical establishment for the hypotheses. It explains not only the relationship between variables in the model, but also presents the rationale behind the inclusion of the control variables.

Servant Leadership

The concept of servant leadership was proposed about four decades ago by Greenleaf (1977) who advanced that the primary responsibility of leaders is to serve their followers (Yukl, 2010). Servant leadership, as it was defined, is more than a mere management technique. It is a lifestyle embedded in and led by the natural feeling that the leader not only wants to serve but to serve first (Parris & Peachey, 2013). As Parris and Peachey recall, many scholars consider Jesus Christ’s life and teachings as constituting the ultimate example of servant leadership. On the opposite of some leadership theories that are defined and assessed only by what leaders do, servant leadership calls for consistency between leaders’ character and acts, and their complete commitment to serve others (Parris & Peachey, 2013).

A servant leader’s goal is to help followers become healthier, wiser and more willing to accept their responsibilities (Yukl, 2010) and to motivate such followers to perform to their fullest capacity (Bambale, 2014). Reaching such a goal will be contingent upon two equally important steps. First, servant leaders seek to develop a one-on-one relationship with followers through good and effective communication (Bambale, 2014). In this first step, leaders listen to followers in order to determine the latter’s needs, aspirations, and potential (Bambale, 2014; Yukl, 2010). The second step consists of using the information amassed in the first step to better serve the followers (Bambale, 2014). Among the behaviors that servant leaders show in their relationship with their subordinates figure the following: (a) integrity, (b) altruism, (c) humility, (d) empathy and healing, (e) personal growth, (f) fairness and justice, and (g) empowerment (Yukl, 2010). Servant leadership has the potential to increase organizational commitment (Yukl, 2010). Research also indicates that servant leadership increases followers’ trust, loyalty and satisfaction with the leader (Yukl, 2010). Among the factors followers utilize to gauge their leader’s effectiveness lies in figuring the leader’s intentions (Yukl, 2010). Consequently, followers are more likely to appreciate and be satisfied with leaders who are perceived to show concern about their needs and well-being, which are aspects of servant leadership (Yukl, 2010). The first hypothesis will then be:

H1: Servant leadership is predicted to yield positive effects on followers’ satisfaction with their leaders.

Follower Satisfaction with the Leader

Employees’ satisfaction regarding their job and their leader is vital to organizational outcomes, notably performance (Scarpello & Vandenberg, 1987). Employee satisfaction is a feeling and an attitude that workers have about their job that results from their opinion of the job and their perception of their superior (Ivancevich, Konopaske, & Matteson, 2008). Notwithstanding an attitude is an intrinsic part of employees’ personality, yet it determines their behavior at work (Ivancevich, Konopaske, & Matteson, 2008). Attitudes, which center satisfaction, are determined by three elements, namely cognition, affect, and behavior (Roe & Ester, 1999). Cognition refers to what employees know about themselves and the work environment. Affect is the emotional element of the attitude. Cognitive dissonance occurs when there are discrepancies between attitudes and behaviors (Ivancevich, Konopaske, & Matteson, 2008).

One of the determinants of employees’ satisfaction with the leader is affect that refers to their feeling about such leader (Ivancevich, Konopaske, & Matteson, 2008). Employees’ feeling has both antecedents and consequences (Roe & Ester, 1999; Scarpello & Vandenberg, 1987). Followers’ feeling regarding effective leaders is contingent upon the latter’s performance, but also their attitudes and behaviors (Eden & Leviatan, 1975; Yukl, 2010). One of the theories that explain the positive outcome of follower satisfaction with the leader is that of referent power according to which employees pleasingly carry out responsibility leading to high performance simply because they admire the leader (Yukl, 2010).

The Moderating Variables

Sharma, Durand and Gurarie (1981) inform that moderators usually belong to two categories. The first category of moderating variables is called homologizer. They influence the strength of the relationship between the predictor and the criterion, but do not interact with the dependent variable. The second category includes pure and quasi moderator variables. They interact with the dependent variable and also influence the strength of the relationship in that they basically modify the forms of such relationship. The three moderating variables employed in this study, namely job demands, fairness in pay and perceived organizational support belong to the second category in that they all interact with the dependent variable and their presence is expected to modify the effects of servant leadership on follower satisfaction with the leader.

Job demands. According to Panatika, O’Driscollb, and Anderson (2011), job demands designate the physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that require constant physical and/or psychological effort or skills from employees to complete the task. Notwithstanding job demands are not necessarily negative, however to meet these demands or expectancies, employees may need to make tremendous efforts that can turn to be hectic and stressful (Meijman & Mulder, 1998). Job demands have the potential to affect employee’s well-being (Panatika, O’Driscollb, & Anderson, 2011). Researchers have utilized the stressor-strain perspective as the theoretical basis to explain the negative effects of job demands on both employees’ well-being and attitudes (Panatika, O’Driscollb, & Anderson, 2011).

Although employees evaluate stressful situations as either potentially threatening or potentially stimulating efforts that will lead to growth, mastery, or even to future benefits and consequently show different types of attitudes and behaviors to different types of stressor (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Panatika, O’Driscollb, & Anderson, 2011), yet all stressors have, in a sense, the potential to generate pressure and strain (Podsakoff, LePine, & LePine, 2007). That is, in general job demands affect employees’ emotions not only toward the organization, but also toward the leader whose responsibility is to insure that those demands are effectively met (Podsakoff et al., 2007). Leadership literature shows that job demands are associated with several psychological outcomes including strain, turnover intentions and job satisfaction that are related to employees’ mood (Panatika, O’Driscollb, & Anderson, 2011). Yukl (2010) purports that the follower’s mood has the potential to affect their perceptions of a leader to the point that these perceptions may be positive when they are satisfied with the work and the leader, and negative when they are under stress and unsatisfied. Consequently, the following hypothesis will be:

H2: Job demands are predicted to moderate the effects of servant leadership on employees’ satisfaction with a servant leader to the point that (such effects will be negative with job demands.

Fairness in pay. It has been demonstrated that when rewards distribution is connected with pay, it yields remarkable impacts on employees’ attitudes and behaviors (Porter, Bigley, & Steers, 2003). Consequently, the way pay is administrated within organizations has been highly discussed and explored in organizational leadership literature and studies (Diekmann, Samuels, Ross, & Bazerman, 1997; Lawler, 1987). Pay unquestionably remains one of the most vital outcomes for employees in an organization (Gupta & Shaw, 1998; Shaw & Gupta, 2001). Since pay is central in the work lives of so many employees (Shaw & Gupta, 2001), much research has been conducted in order to examine employees’ attitudes about it (Lawler & Jenkins, 1992; Miceli & Lane, 1991). Most of this research investigates the consequences of pay on employees’ attitudes, and that is related to these employees’ mood (Miceli & Mulvey, 1998). Undeniably, it is humanly natural and demonstrated in research that most, if not all, employees would prefer to receive more pay than less (Shaw & Gupta, 2001). Leadership literature has revealed evidence of existing relationship between pay fairness and some job attitudes including satisfaction leading to citizenship behaviors (Lee, 1995) and commitment (Cohen & Gattiker, 1994). Pay fairness is related to pay satisfaction in leadership literature (Wu & Wang, 2008) and is considered as the overall positive or negative feelings or perception employees hold concerning their pay. Research has indicated that employees’ perception of justice is highly contingent upon their satisfaction with pay (Wu & Wang, 2008). Research efforts and results on perceived justice and pay satisfaction have led to combined results. That is, it yields evidence relating to both the role of pay fairness dimensions and their impacts on pay satisfaction that naturally lead to organizational outcomes (Wu & Wang, 2008).

When employees see themselves in conditions of social exchange, such as receiving fair pay, they become more involved in the organization and are willing to exhibit affective commitment which includes greater loyalty to this organization, consequently to the leader as well (Blau, 1964; Wu & Wang, 2008). Additionally, Robbins, Summers, and Miller (2000) explain how perceived justice effects performance and the related exchange relationship. It can be concluded that fairness in pay plays a key role in enhancing employees’ loyalty and performance in an organization that are, according to Yukl (2010), antecedents of these employees’ satisfaction with the leader. Consequently, the third hypothesis will be:

Hypothesis 3: Fairness in pay is predicted to moderate the effects of servant leadership on employee satisfaction with the leader to the point that the effects will be positive with perceived fairness in pay.

Perceived organizational support. This is the organizational leadership theory that refers to the perception of employees apropos the commitment of the organization to them (Noruzy, Shatery, Rezazadeh, & Hatami-Shirkouhi, 2011). It relates to employees’ general feelings and beliefs regarding how the organization acknowledges, appreciates and values their work, and consequently shows concerns about them (Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhodes, 2002). As Noruzy et al. suggest, the existing definitions of perceived organizational support in leadership literature insinuates that it creates among employees the implicit feeling that they owe their support to the organization in return.

Perceived organizational support produces positive results in both employees’ attitudes (Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhodes, 2002), and behaviors (Noruzy, Shatery, Rezazadeh, & Hatami-Shirkouhi, 2011). It increases employees’ commitment to the organization to the point that they feel obligated to care about the organization’s well-being (Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997). It also increases employees’ loyalty to the organization and consequently to the leader who is perceived to be instrumental in creating and maintaining such support (Wayne, Shore, & Liden, 1997).

Literature has shown that employees’ opinion of organizational support is highly shaped by their perceptions of their leaders’ intentions and actions. In this regard, Conklin, Lambert, Brenner, and Cranage (2009) have remarked that employees often view the actions taken by leaders as indications of the organization’s intention and not simply as these leaders’ personal motives. Consequently, employees with perceived organizational support will more likely hold good images and make positive attributions about not only the organization, but also their leaders to such a point that they will show high satisfaction with both the organization and the leader (Conklin, Lambert, Brenner, & Cranage, 2009). The fourth hypothesis will then be:

Hypothesis 4: Perceived organizational support is predicted to moderate the effects of servant leadership on follower satisfaction with a servant leader to the extent that the effects will be positive when employees perceive organizational support.

Control Variables

The present research includes two control variables. The first one is the time the follower has spent working with the leader. A follower satisfaction with a leader is highly contingent upon the exchange relationship between the two (Graen, Novak, & Sommerkamp, 1982). The exchange relationship leading to follower satisfaction is developed through three stages (Graen & Scandura, 1987): (a) the initial stage in which followers evaluate leaders’ attitudes and motives, (b) the second stage in which followers show loyalty, respect and admiration based on the evaluation made in the first stage, and (c) the third stage in which followers show commitment to both the organization and the leader (Yukl, 2010). Satisfaction with leaders is progressive and can be affected by the time followers have been working with such leaders (Graen & Scandura, 1987); Yukl, 2010). The second control variable that can also affect follower satisfaction with the leader is gender differences between the former and the latter (Malangwasira, 2013). Consequently, gender differences were controlled for in the analysis as well.

Method

This study employed the quantitative research method of survey questionnaire with the purpose of generalizing from the sample to a population (Creswell, 2009). The research was cross-sectional in that data were collected at one point in time (Creswell, 2009). Since the participants do not speak English, the questionnaires were translated into Creole and French, the two official languages of Haiti where the research was conducted. The questionnaires were self-administered. This was more convenient for the respondents and kept their time commitment low for this research since they work on a daily basis and did not have much extra time.

Population, Sample, and Participants

This study employed a random sample in order to provide each individual in the targeted population an equal chance to be selected or to fill out the questionnaire (Creswell, 2009). Participants were recruited from five small organizations in the north area of Haiti: a) three high schools, b) a radio station, and c) a small hospital. Based on Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham (2006) suggesting 20 respondents for each independent variable to effectively conduct hierarchical regression analysis, the study planned for 180 participants to fill out the questionnaire, yet only 132 questionnaires were filled out and returned, among which 123 were found to be suitable for analysis.

Instrumentation

The research survey is a combination of five questionnaires: a) Servant Leadership, which is a single scale with ten items developed by Winston and Field (2015), with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .96 (b) Satisfaction with my Supervisor, a single eighteen-item scale with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .96 developed by Scarpello and Vandenberg (1987),

(c) the seven-item subscale of job demands with α =. 88 of Job Demands and Decision Latitude questionnaire, created by Karasek (1979), (d) Pay Satisfaction Questionnaire, developed by Heneman and Schwab (1985) with α =. 88, constituting of 18 items measuring a single dimension and (e) Perceived Organizational Support designed by Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchinson, and Sowa (1986), with α = .95, including 17 items measuring a single construct. Notwithstanding the validity and reliability of these scales were already established in the literature, a factor analysis test was conducted with the sample to reassess their evidence for the present study. For this particular study, Servant Leadership shows a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .85, Satisfaction with Supervisor, .96, Job demands, .82, Pays Satisfaction, .96, and Perceived Organizational Support, .86. Demographic questions pertaining to gender differences between leaders and followers as well as the time since followers have been working with the leader were also added to the survey questionnaire.

Results

This section presents the research findings from the analyses performed to test the four hypotheses. The study proposed to examine how servant leadership would predict follower satisfaction with the leader and whether such prediction would be moderated by three situational variables, namely job demands, fairness in pay, and perceived organizational justice. The purpose was articulated with more details through the hypotheses.

Assessing the Effects of Servant Leadership on Satisfaction with the Leader

To test whether servant leadership would yield positive effects on followers’ satisfaction with their leaders as anticipated in hypothesis 1, hierarchical regression analysis was conducted while controlling for gender and the number of years working with the leader. Gender and the number of years working with the leader were entered at Step 1, and they explained 1 % of the variance in satisfaction with the leader with F (2, 100) = .62, p = .54 > .05. After entering servant leadership, which is the independent variable at Step 2, the total variance explained by the model became 42%, F (3, 99) = 23.65, p =.00 < .05. Servant leadership explains an additional 41% of the variance in satisfaction with the leader, after gender and tenure with the leader have been controlled. This is indicated by the R2 change which is .41, F change (1, 99) = 68.88, p = .00 < .05. The coefficients table for model 2 shows that servant leadership (b = .64, p = .00 < .05) yields some significant effects on satisfaction with the leader. These results support hypothesis 1, which predicted significant effects of servant leadership on satisfaction with the leader.

| Variables | b | p |

| Gender | .09 | .25 |

| Year with the Leader | -.12 | .12 |

| Servant Leadership | .64 | .00 |

Assessing the Moderating Effects of Job Demands

In order to explore whether job demands would moderate the effects of servant leadership on follower satisfaction with the leader, another hierarchical regression analysis was conducted, but this time with three steps. Gender and the number of years with the leader were entered at Step 1, and they explained 1 % of the variance in satisfaction with the leader with F (2, 93) =. 57, p =.57 > .05. The independent variable, namely servant leadership, and the moderating variable, job demands, were entered at Step 2, and the total variance explained by the model became 43 %, F (4, 91) = 16.94, p = .00 < .05. The independent variable and the moderator put together explain an additional 42% of the variance in follower satisfaction with the leader, after gender and tenure have been controlled. This is indicated by the R2 change=.42, F change (2, 91) = 32.91, p = .00 < .05. The interaction product of the independent variable and the moderating variable was entered in Step 3. The total variance explained by the whole model remains 43 %, F (5, 90) = 13.82, p =.00 < .05. The coefficients table for model 3 shows that servant leadership remains significant (b =.93, p = .00 < .05) and job demands are not (b = .74, p = .22 > .05). It additionally indicates that the moderating effects of job demands are not present, with b = -.70, p = . 28 > p = .10, as recommended by McClelland and Judd (1993). Therefore, hypothesis 2 is not supported.

| Variables | b | p |

| Servant Leadership | .93 | .00 |

| Job Demands | .74 | .22 |

| Servant Leadership*Job Demands | – .70 | .28 |

Assessing the Moderating Effects of Pay Satisfaction

A hierarchical regression analysis similar to the one conducted to assess the moderating effects of job demands on the effects of servant leadership on employee satisfaction with the leader was performed, but this time with pay satisfaction as the moderating variable. The two control variables were entered at Step 1, and they explained, as in the previous test, 1 % of the variance in satisfaction with the leader with F (2, 87) =. 54, p = .60 > .05. Servant leadership and pay satisfaction, the moderating variable, were entered at Step 2, and the total variance explained by the model became 56 %, F (4, 85) = 52.54, p =.00 < .05. These two variables together explained an additional 55% of the variance in follower satisfaction with the leader. This is indicated by the R2 change=. 55, F change (2, 85) = 52.54, p = .00 <. 05. The interaction product of servant leadership and pay satisfaction was entered in Step 3. The total variance explained by the entire model remains 56%, F (5, 84) = 21.23, p = .00 < .05. The coefficients table for model 3 shows that servant leadership remains significant (b =. 50, p = .03 < .05) and pay satisfaction is not (b =.46, p = .40 > .05). The coefficients table also indicates that the moderating effects of pay satisfaction are insignificant, with b = -.05, p = .94 > p = .10. Hypothesis 3 is then not supported.

| Variables | b | p |

| Servant Leadership | .50 | .03 |

| Pay Satisfaction | .46 | .40 |

| Servant Leadership*Pay Satisfaction | – .05 | .94 |

Assessing the Moderating Effects of Perceived Organizational Support

A fourth hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to test the moderating effects of perceived organizational supported as articulated in hypothesis 4. As for the aforementioned hierarchical regression tests, the two control variables were entered at Step 1, and they explained 1 % of the variance in satisfaction with the leader with F (2, 95) =. 58, p = .56 > .05. Servant leadership and perceived organizational support, which is the moderating variable for this time, were entered at Step 2, and the total variance explained by the model became 53%, F (4, 93) = 26.10, p = .00 < .05. These two variables explain an additional 52% of the variance in follower satisfaction with the leader. This can be seen in the R2 change =. 55, F change (2, 92) = 51.10, p =.00 < .05. The interaction product of servant leadership and perceived organizational support was entered at Step 3. The total variance explained by the entire model remains 53%, F (5, 92) = 20.7, p = .00 < .05. The coefficients table for model 3 does not reveal servant leadership as significant (b = .37, p = .22 > .05), and a similar result was found for perceived organizational support (b =.32, p = .47 > .05). The same table also shows that perceived organizational support does not moderate the effects of servant leadership on employee satisfaction with the leader, with b = .12, p =. 85 > p = .10. Consequently, hypothesis 4 is not supported either.

| Variables | b | p |

| Servant Leadership | .37 | .22 |

| Perceived Organizational Support | .32 | .47 |

| Servant Leadership*Perceived Organizational Support | .12 | .85 |

Discussion

The results of the first regression analysis show that servant leadership yields positive effects on employee satisfaction with the leader (b =.64, p = .00 < .05). This theoretically indicates that employees are more likely to experience satisfaction with a leader who shows servant leadership behavior. This supports the first hypothesis and is consistent with the literature that indicates that servant leadership increases followers’ trust, loyalty and satisfaction with the leader (Yukl, 2010). Servant leaders’ main focus is not the organization, but the follower whose needs the former strive to attend (Greenleaf, 1977). It then becomes natural for followers to develop and show their appreciation for such leaders.

The first regression analysis run to test whether job demands would moderate the effects of servant leadership on employee satisfaction with the leader records no effects. Moderating effects occur in regression analysis when the variable called the moderator has the ability to change the form of the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable (Hair et al., 2006). Since no effects are registered, this theoretically indicates that even with the presence of job demands as a moderator, the effects of servant leadership on employee satisfaction with the leader are not altered at all. Job demands usually yield negative effects on employees’ attitudes (Panatika, O’Driscollb, & Anderson, 2011). However, it seems that employees feel so comfortable with servant leaders that the stress produced by job demands does not alter their appreciation for such leaders.

The second hierarchical regression analysis that was performed to test whether fairness in pay would moderate the effects of servant leadership on employee satisfaction with the leader does not show any such effects either. This theoretically signifies that the fact that employees believe they receive fair pay or not, such perception does not affect their appreciation for a servant leader. Satisfaction and fairness, when it comes to pay, are highly related (Wu & Wang, 2008). Servant leaders are perceived to want the best for their employees including providing them with the pay they deserve (Yukl, 2010). Consequently, the satisfaction employees would experience from their pay may have already been immersed in their satisfaction with the leader who is highly instrumental in distributing pay.

The third hierarchical regression test conducted to examine the moderating effects of perceived organizational support on the effects of servant leadership on employee satisfaction with the leader indicates no effects. Theoretically, this means that employees’ perception of an organization that is supportive to them does not significantly modify their satisfaction with their leader who appears to show servant behaviors. The theory of perceived organizational support explains the general feelings and beliefs employees hold regarding an organization that shows concerns about them (Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vandenberghe, Sucharski, & Rhodes, 2002). In a sense, perceived organizational support is similar to servant leadership except for the fact that for servant leadership it is the individual leader that shows such concern while for perceived organizational support it is the organization as a whole that exhibits the concern. Additionally, and as Wayne, Shore, and Liden (1997) explain it, leaders are the ones that are perceived to create and maintain such support. Consequently, employees’ appreciation or satisfaction with the leader may be almost the same as their appreciation with the organization.

However, the study presents some limitations. First, it should be noted that the sample size and the number of questionnaires returned were not sufficient to adequately test the model with all its variables. So, a greater number of completed and returned questionnaires would allow to test the hypotheses with greater confidence. Second, because of the relatively high level of analphabetism coupled with the fact that research is at its early stage in Haiti, the respondents are not really comfortable with participating in research, even less with the method of survey questionnaire. Third, most participants are high school teachers and the concept of organization is limited to their experience within the classroom and their relationship with the principal. A more diverse population would enhance the research.

The study can be replicated in other countries where perhaps people are more accustomed to research and with larger and more diverse samples. Additionally, the theory of leader-member exchange relationship may be included as a situational variable in the model. On the opposite of job demands, fairness in pay and perceived organizational support whose measures are unidirectional, leader-member exchange relationship can be low or high. Its inclusion in the model may offer a good opportunity to test whether it would moderate the effects of servant leadership on employee satisfaction with the leader.

Conclusion

The research proposed to explore the effects of servant leadership on employee satisfaction with the leader and the influence of some situational variables, namely job demands, fairness in pay and perceived organizational support, on these effects. The results of the first regression test support the first hypothesis, which expected servant leadership to yield positive effects on employee satisfaction with the leader. Interestingly, none of the proposed moderators was found to yield significant effects on the predicted relationship between servant leadership and employee satisfaction with the leader.

Nevertheless, notwithstanding its limitations, the study confirms that servant leadership is of a high level of importance for organizations. Servant leadership puts the emphasis on the welfare of the subordinate rather than the glorification of the leader (Hale & Fields, 2007). Servant leaders’ concern for employees is likely to augment their trust, loyalty and satisfaction with such leaders (Yukl, 2010). Notwithstanding servant leadership focus is the employee, it indirectly yet highly benefits the organization as a whole, particularly in that it contributes to the employee-oriented culture that has the potential to attract and retain talented and committed employees (Yukl, 2010). However, the absence of the moderating effects in the study may also be explained by the fact that some of the behaviors of servant leadership are also included in other leadership theories. Consequently, and as Yukl suggests, still more research is needed to assess the uniqueness of scales of this construct.

About the Author

Duky Charles is now in the dissertation process for his Ph.D as an Organizational Leadership student at Regent University. He is currently the vice-president of academic affairs at North Haiti Christian University. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Duky Charles at dukycha@mail.regent.edu.

About Regent

Founded in 1977, Regent University is America’s premier Christian university with more than 11,000 students studying on its 70-acre campus in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and online around the world. The university offers associate, bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in more than 150 areas of study including business, communication and the arts, counseling, cybersecurity, divinity, education, government, law, leadership, nursing, healthcare, and psychology. Regent University is ranked the #1 Best Accredited Online College in the United States (Study.com, 2020), the #1 Safest College Campus in Virginia (YourLocalSecurity, 2021), and the #1 Best Online Bachelor’s Program in Virginia for 13 years in a row (U.S. News & World Report, 2025).

About the School of Business & Leadership

The School of Business & Leadership is a Gold Winner – Best Business School and Best MBA Program by Coastal Virginia Magazine. The school also has earned a top-five ranking by U.S. News & World Report for its online MBA and online graduate business (non-MBA) programs. The school offers both online and on-campus degrees including Master of Business Administration, M.S. in Accounting (Tax or Financial Reporting & Assurance), M.S. in Business Analytics, M.A. in Organizational Leadership, Ph.D. in Organizational Leadership, and Doctor of Strategic Leadership.

References

Bambale, A. J. (2014). Relationship between Servant Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: Review of literature and future research directions. Journal of Marketing and Management, 5 (1), 1-16.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: Wiley.

Cohen, A., & Gattiker, U. E. (1994). Rewards and organizational commitment across structural characteristics: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business and Psychology, 9, 137-157.

Conklin, M. T., Lambert, C. U., Brenner, M., & Cranage, D. A. (2009). Relationship of directors’ beliefs of perceived organizational support and affective commitment to point in time of development of school wellness policies. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 12, 110–119.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (3rd ed.) Los Angeles: Sage Publication.

Diekmann, K. A., Samuels, S. M., Ross, L., & Bazerman, M. H. (1997). Self-interest and fairness in problems of resource allocation: Allocators versus recipients. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 1061–1074.

Eden, D., & Leviatan, U. (1975). Implicit leadership as a determinant of the factor structure underlying supervisor behavior scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 736-741.

Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchinson, S., & Sowa D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 500–507.

Eisenberger, R., Stinglhamber, F., Vandenberghe, C, Sucharski, I. L., & Rhodes, L. (2002). Perceived supervisor support: contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. Journal of Applied Psychology. 87(3), 565-573.

Graen, G., & Cashman, J.F. (1975). A role making model of leadership in formal organizations: A developmental approach. In J. G. Hunt & L. L. Larson (Eds.), Leadership frontiers. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press.

Graen, G., Novak, M., & Sommerkamp, P. (1982). The effects of leader-member exchange and job design on productivity and satisfaction: Testing a dual attachment model. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 30, 109-131.

Graen, G. B., & Scandura, T. (1987). Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. Research in Organizational Behavior, 9, 175-208.

Greenleaf, R. K. (1977). Servant Leadership: A Journey into The Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

Gupta, N., & Shaw, J. D. (1998). Let the evidence speak: Financial incentives are effective!! Compensation and Benefits Review, 30(2), 28-32.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2005). Multivariate Data Analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hale, J.R. & Fields, D.L. (2007). Exploring servant leadership across cultures: A study of followers in Ghana and the USA. Leadership, 3 (4), 397-417.

Heneman, H. G, & Schwab, D. P. (1985). Pay satisfaction: Its multidimensional nature and measurement. International Journal of Psychology. 20(2), 129-141.

Ivancevich, J. M., Konopaske, R., & Matteson, M. T. (2008). Organizational Behavior and Management (8e ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Karasek, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24, 285-308.

Lawler, E. E., III (1987). The design of effective reward systems. In J. W. Lorsch (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 255–271). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Lawler, E. E., III, & Jenkins, G. D., Jr. (1992). Strategic reward systems. In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (3rd ed., pp. 1009-1055). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Lazarus, R.S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York, NY: Springer.

Lee, C. (1995). Prosocial organizational behaviors: The role of workplace justice, achievement striving, and pay satisfaction. Journal of Business and Psychology, 10, 197-206.

Malangwasira, T. E. (2013). Demographic differences between a leader and followers tend to inhibit leader-follower exchange levels and job satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Culture, Communications and Conflict, 17(2), 63-105.

McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993) Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderators. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 376–390.

Meijman, T.F., & Mulder, G. (1998). Psychological aspects of workload. In P.J.D. Drenth & H. Thierry (Eds.), Handbook of work and organizational psychology (Vol. 2) (pp. 5-33). Hove: Psychology Press.

Miceli, M. P., Jung, I. j., Near, J. P., & Greenberger, D. B. (1991). Predictors and outcomes of reactions to pay-for-performance plans. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 508- 521.

Miceli, M. P. & Lane, M. C. (1991). Antecedents of pay satisfaction: A review and extension. In K. Rowland & G. R. Ferris (Eds.), Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management. (pp. 235-309). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Miceli, M. P., & Mulvey, P. W. (1998). Satisfaction with pay systems: Antecedents and consequences. Paper presented at the Annual Meetings of the Academy of Management, San Diego, CA.

Noruzy,A., Shatery, K., Rezazadeh, A., &, Hatami-Shirkouhi, L. (2011) Investigation of the relationship between organizational justice, and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating role of perceived organizational support. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 4 (7), 842-847.

Panatika, S. A., O’Driscollb, M. P., & Anderson, M. H. (2011). Job demands and work- related psychological responses among Malaysian technical workers: The moderating effects of self-efficacy. Work & Stress, 25(4), 355-370.

Parris, D. L., Peachey, J. W. (2012). A systematic literature review of servant leadership: Theory in organizational contexts. Journal of Business Ethics, 113, 377–393.

Podsakoff, N.P., LePine, J.A., & LePine, M.A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor- hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 438-454.

Porter, L. W., Bigley, G. A., & Steers, R. M. (2003). Motivation and work behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Roe, R., & Ester, P. (1999). Values and work: empirical findings and theoretical perspectives. Applied Psychology: an International Review, 1-21.

Robbins. T. L., Summers, T. P. & Miller, J. L. (2000). Intra- and inter-justice relationships: Assessing the direction. Human Relation, 53(10), 1329-1355.

Scarpello, V., & Vandenberg, R. (1987). The Satisfaction with my Supervisor Scale: Its utility for research and practical application. Journal of Management, 34, 451-460.

Sharma, S., Durand, R. M., & Gurarie, O. (1981). Identification and analysis of moderator variables. Journal Of Marketing Research, 18, 291-300.

Shaw, J. D., & Gupta, N. (2001). Pay fairness and employee outcomes: Exacerbation and attenuation effects of financial need. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology, 74(3), 299-320.

Wayne, S.J., Shore, L.M., & Liden, R. C. (1997). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy Management Journal, 21(5), 82–111.

Winston, B. & Fields, D. (2015). Seeking and measuring the essential behaviors of servant leadership. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal. 36(4) 413-434.

Wu, X., & Wang, C. (2008). The impact of organizational justice on employees’ pay satisfaction, work attitudes and performance in Chinese hotels. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 7(2), 181-195.

Yukl, Gary (2010). Leadership in Organizations. (7th ed.) New Jersey: Prentice Hall.