How Christ’s Coming Instilled True Justice in the World: An Interview with Dr. Jeffrey Brauch

Though the sky shimmered with twinkling stars and a chorus of angels, he was visited by shepherds — humble caretakers of sheep. Despite his rather unglamorous birth, the lowborn son of God would change the world and bring forth true justice.

In Luke 4:18 he said, “The Spirit of the Lord is on me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind, to set the oppressed free.”

Christ came and brought justice.

But what if Christ hadn’t come? How was his coming formative to the concept of justice? And what role do his followers play in promoting justice?

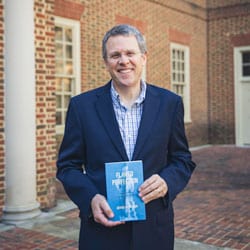

Regent University School of Law LL.M. program director Dr. Jeffrey Brauch is the executive director for the Center for Global Justice, Human Rights & the Rule of Law.

“The very fact he [Christ] became human … that he would take on human form, and that he would live a life bearing the indignities that he had to bear, being treated as he did, just showed how much God values us,” said Brauch. It tells us, ‘Wow, God cares about humans,’” he added.

Before Jesus came, those who contributed little to society’s utility were unvalued; trodden, cast out, left to starve and die, plebian waste in the eyes of many.

“He raises the poor from the dust and lifts the needy from the ash heap; he seats them with princes and has them inherit a throne of honor. For the foundations of the earth are the LORD’s; on them he has set the world,” reads 1 Samuel 2:8.

The inability or refusal to see life as precious, as Christ did, is the root of various issues regarding justice. Dr. Brauch addresses them in his book, Flawed Perfection: What It Means To Be Human & Why It Matters For Culture, Politics, And Law.

“The Christian view is that all humans have equal dignity and worth — regardless of age, sex, race, size, wealth, health or mental condition,” writes Brauch. “This dignity is not based on our achievement or ability. We are not the source of our own dignity; it comes from our creator.”

For Christians, this is the bedrock of true justice — that all life is equally valuable and should thus be protected and defended. Living freely is a right found in being a creature created with dignity in the image of God.

In it, Brauch articulates how even those who professed Christ as lord engaged in genocide. Throughout numerous instances, Christians, he writes, had their identity rooted deeper into their culture rather than their faith, and therefore embraced the actions of their culture, even if such actions were abhorrently evil.

In his writing, he specifically comments on the Rwandan genocide in which Hutus carried out acts of violence against Tutsis, another ethnic group in the country. “Their real identity was that they were Hutus. What was sort of core to them? What was the thing that shaped their value? [It] was being a Hutu, more than being a Christian,” Brauch said. “When it came down to it, their decision — that they were willing to kill neighbors or even co-workers, or even family members sometimes — was because, ‘well, that’s what I do as a Hutu. I need to do what Hutus do,’ rather than, ‘what would Christ tell me to do?’”

Christians must find “priorities from [their] identity as Christians,” rather than from culture, especially one which denounces the value of life according to Brauch.

Seeing our families and loved ones this Christmas season should not be taken for granted. Thousands of individuals, here in the land of the free and the home of the brave, are not free, but enslaved and trafficked.

Sometimes it’s hard to see God’s justice, even in evil’s darkest nighttime hour.

The great American poet Henry Wadsworth echoed this sense of gloomy despair in his poem turned Christmas carol, “I heard the Bells on Christmas Day.”

The first stanza reads, “I heard the bells on Christmas day,

Their old familiar carols play,

And mild and sweet their songs repeat,

Of peace on earth good will to me.”

Two stanzas further, Longfellow writes, “And in despair I bowed my head,

There is no peace on earth I said,

For hate is strong and mocks the song,

Of peace on earth, good will to men.”

He wrote the poem on Christmas day 1863. It’d been a year of vicious fighting. Battles like Gettysburg and Chickamauga, the two costliest engagements of the civil war, had bled America of tens of thousands of young men. That summer, his own son was badly hurt at the battle of Malvern Hill in Virginia. Two years earlier, his wife was killed in a fire. Where was justice for Longfellow? Where was hope in a shattered family, a nation torn asunder by boys in blue and grey?

Indeed a culture, maimed by the curse of sin and death, cannot produce true justice on its own.

However, two stanzas later, he rejects the notion that the only force reigning over his country is one of hopelessness: “Then rang the bells more loud and deep God is not dead,

nor does he sleep (peace on earth, peace on earth)

The wrong shall fail, the right prevail,

With peace on earth, good will to men”

Is there darkness in the world? Yes.

As long as there is sin in the world, so there will be evil. But Christ came. In his kingdom, the slave and the free stand as equal, and the latter works to break the chains of the former.

Jesus honored those society abhorred, or simply cast away as useless, with love, grace, kindness and mercy. He brought salvation through his blood and a gospel that forever revolutionized culture. Jesus came not only to save mankind, but to bring justice.

Justice for the world is not absent, but is found in a kingdom that cannot be divided or pieced apart, in a kingdom where the “wrong shall fail, the right prevail, with peace on earth, good will to men.”