Russian Organizational Leadership: Lessons from the Globe Study

This paper summarizes the authors’ findings on organizational leadership in Russia through the GLOBE cross-cultural research program and further develops an interpretation of empirical data on Russian business leadership. The authors discuss factors of effective leadership rooted in the country’s history, highlight relative scores on universal leadership attributes, interpret culture- contingent leaders’ characteristics, and summarize the influence of culture on effective leadership in a transitional society.

Among the important applications of contemporary leadership theories is the articulation of organizational leadership in diverse societies. Leadership is defined by universal as well as country-specific/culture-specific characteristics. While much has been done on leadership attributes and behaviors in industrialized countries, it is clear that in countries in transition to democracy and the free market leaders follow their own customs to encourage, motivate, and enable others to contribute to the success of the organizations of which they are members.

In the last decade, scholars have discussed Russian culture and its impact on business and management practices (Elenkov, 1997; Grachev, 2001; Michailova, 2000; Naumov, 1996; Naumov & Puffer, 2000; Puffer, 1992). In particular, they have analyzed the profile of the Russian business leader and compared the values and behaviors of Russian to American entrepreneurs (Kats de Vries, 2000; Hisrich & Grachev, 2001). However, these findings were neither placed into a larger international comparative framework nor linked to universal leadership attributes for comparative purposes.

This paper presents findings on organizational leadership in Russia from the large-scale cross-cultural research program, Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE), conducted in 62 counties. The program is based on a culturally endorsed implicit leadership theory (CLT) that focuses on beliefs about effective leaders shared by members of an organization or society (House, 1997, 1999, 2004). GLOBE findings position Russia in a cluster framework (Bakacsi, Takacs, Karacsonyi, & Imrek, 2002) and summarize its cultural profile (Grachev, 2004) and its CLT leadership profile in a cross-cultural context.

After reviewing the historically developed sources of effective leadership in Russia, the remainder of the article presents our empirical findings and relative scores on leadership dimensions that are universally perceived as contributors to or inhibitors from outstanding leadership.

Genesis of Russian Organizational Leadership

Modern societal culture in Russia is determined by three sets of factors: (a) traditional features, historically developed through centuries; (b) influence of the 20th century totalitarianism; and (c) radical revolution in values, beliefs, and behaviors through the transitional 1990s and early 2000s (Grachev, 2004). These factors may help to predict the profile of an effective Russian organizational leader.

Historically developed characteristics of Russian culture are rooted in Slavic history, Orthodox religion, specific features of natural environmental, and unique social capital. Holistic and influential, Slavic-Orthodox culture is regarded as one of the few “global cultures” (Huntington, 1993). Through the centuries, Russia has integrated basic values of both the West and the East – reason and inspiration. It has served as a bridge between Western and Eastern cultural traditions with a certain psychological dependence on both. Its national character combined such qualities as habitual, patient struggle with misfortune and hardship; the ability to concentrate efforts; the ability to cooperate across a large geographic distance, impersonal collectivism; humanism; and the search for truth (Chaadaev, 1991; Kluchevskii, 1904).

While Russia was growing through the centuries, its leaders were traditionally associated with the state, religion, or the military. The Russian Orthodox Church greatly influenced society, and several spiritual leaders were deified. Peter the Great, who began “Westernization” in the 18th century by autocratic and barbarian means, was an admired military leader. Business leaders in his time were traders who, along with the military, created Europe’s strongest military- industrial complex of those times. Later, the economic liberalism of Catherine the Great attracted the highest-ranking Russian nobles to entrepreneurship. The industrial revolution in the 19th century brought the real spirit of private initiative and leadership to Russia. Talented business leaders such as Morozov, Knopp, and Ryabushinski founded successful business empires in Russia and introduced many organizational innovations, including charitable initiatives.

In the 20th century under Communism, in contrast to the West, Russia appeared to have largely retained, even in periods of rapid industrial expansion, an autocratic or patrimonial system (single-centered). This sharply limited the autonomy of economic units in the use and disposal of resources and preserved for those in political control the right, if only de jure, to determine the pace and pattern of economic development (Guroff & Carstensen, 1983). Russian leadership characteristics were modified by specific Soviet (totalitarian) traits such as a perception of the environment as hostile and dangerous, supremacy of society’s goals over the individual’s, and a relativistic view of morality with an acceptance of double standards in life (Mikheyev, 1987). However, even within the Soviet command system, there existed a vigorous level of entrepreneurial response and positive leadership heritage, including military victories in the Second World War, courageous behaviors, and great technical projects.

In the 1990s, the transitional Russian economy was run by a small number of financial- industrial groups, arguably more powerful than the state. The stage of aggregating capital by selling state property (“privatization stage”) was over, and the new epoch could be defined as the stage of “managing capital effectively,” with the oligarchs – leaders of industrial and financial empires – displaying a new leadership model for the Russian economy.

Later, in the early 2000s, the political and economic landscape experienced a new shift. With the rise of a state bureaucracy supported by security corps, the government confronted disloyal oligarchs and selectively re-evaluated the results of the “wild” privatization of the 1990s. One of the major consequences of these changes was strengthened state control over economic development at the expense of democratic institutions. Russian President Vladimir Putin coined the term “managed democracy” to define the unique Russian path to economic prosperity. Bureaucratic rules limited entrepreneurial initiative, creativity, and the ability to successfully and ethically interact with Russia’s counterparts in the global economy.

The heterogenous kaleidoscopic culture of Russia’s current transitional society is different from the homogenous Soviet culture. Business leaders and managers in Russia are motivated by one or a combination of the following business philosophies: bureaucratic, based on active initiatives under state-run bureaucratic supervision; pragmatic, based on maximum profitability on a technocratic basis; predatory, based on achieving success through tough suppression of rivals including Mafia connections, growth by any means, and cheating on partners, consumers, and the state; and socially responsible, based on linking business to the promotion of national interests, the resolution of social problems, and universal human values (Ageev, Gratchev, & Hisrich, 1995).

The current transitional economy makes the carriers of those business philosophies very diverse, with a variety of economic and political interests. In the literature, a number of similar typologies exist to differentiate these carriers. While the typologies often do not go far beyond informal observations, they help to better explain the diversity of the Russian management community.

Our typology identifies Old Guard, New Wave, and International Corps by linking their root characteristics to the stages of Russian business history (Ageev et al., 1995). The first group, the Old Guard, consists of those who proved their talents as leaders in large-scale projects such as managing technological innovations. The Old Guard exploit their access to key decision- making centers and information and use bureaucratic connections and control of resources.

These people still keep leading positions in large industrial corporations or in internationally competitive sectors of the economy (oil-and-gas, aerospace, shipbuilding, and others). The second group, the New Wave, emerging from economic reform, follows a different road to economic independence by searching for innovations and reflecting advanced economic thinking. They are leaders of the former shadow economy, which has been being increasingly legalized and are former Communist party functionaries or military officers who successfully transformed into businessmen. A large proportion of this group is young people, hungry for entrepreneurial success. Another group of people, who can be called Unwilling Entrepreneurs, are forced to take initiatives due to fear of unemployment and are now involved primarily in small-scale trade transactions. Finally, there is a group of foreign businessmen (International Corps) that operates in the Russian market, including representatives of the Russian diaspora.

A similar system of categorizing Russian business leaders is suggested by M. de Vries (2000). He identifies two groups separated by a substantial generation gap. In the first group he places young enthusiastic, talented people who recognize the opportunities of the new open society. This group includes former black marketers turning to legitimized business and the children of Party nomenklatura. The administrators and bureaucrats who used to supervise the Soviet economy in the past make up the second group. However, this second group is not homogeneous. One subgroup includes a well connected business elite, retaining privileged positions. The other subgroup among the older generation is focused on self-preservation, making superficial adjustments to maintain their status, often giving only lip service to the new economy.

Globe Design and Russian Sample Composition

This paper summarizes findings on Russian effective leadership as a part of a large-scale cross-cultural research program called GLOBE*. The theoretical base that guides the GLOBE research integrates implicit leadership theory, value/belief theory of culture, implicit motivation theory, structural contingency theory of organizational form and effectiveness, and integrated leadership theory. The central GLOBE proposition is that attributes and entities that distinguish a given culture from other cultures are predictive of the practices of organizations of that culture and predictive of the leader attributes and behaviors that are most frequently enacted, acceptable, and effective in that culture.

The GLOBE cultural dimensions design was based on previous works by Hofstede (1984) and McClelland (1985) and also included the theoretical findings of Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck (1961) and Triandis (1995). Cultural values and practices were measured on a 7-point response scale with respect to nine cultural dimensions that display high within-culture and within-organization agreement and high between-culture and between-organization differentiation: societal collectivism, family collectivism, gender egalitarianism, assertiveness, power distance, performance orientation, future orientation, uncertainty avoidance, and humane orientation.

Several statistical procedures were applied to define the properties of the GLOBE cultural scales (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004). The determination of cultural aggregation was justified by measures that compare the observed variance within a society to the variance expected if there is no within-society agreement. The ICC(1) statistic provided information on the appropriateness of aggregation, comparing the variance between societies with the variance within societies. The reliability of scales was assessed with respect to two random error sources (internal consistency and interrater reliability).

In a similar way, and consistent with the way implicit leadership theories of individuals have been measured in previous research, GLOBE combined trait and behavioral descriptors to reflect relevance to leadership effectiveness (Dunnette & Hough, 1991). These items were also measured on a 7-point scale from a low of “This behavior or characteristic greatly inhibits a person from being an outstanding leader” to a high of “This behavior or characteristic greatly contributes to a person being an outstanding leader.” Respondents reflected on a given definition of effective leadership as the ability of an individual to motivate, encourage, and enable others to contribute to the success of the organization of which they are members.

GLOBE provided evidence that people from different cultural groups (societies) share a high level of agreement on their beliefs about effective leadership and that significant statistical differences exist among cultural groups in their beliefs about leadership. These shared beliefs may be described by the CLT leadership profile. GLOBE research has also identified 21 specific leadership attributes and behaviors that are universally viewed as contributors to or inhibitors from effective organizational leadership. Based on second-order maximum likelihood exploratory factor analysis, the following factors that constitute six global leadership dimensions were identified. Two were found as universal contributors to effective leadership: charismatic/value-based and team-oriented. Two factors were found as culture-sensitive contributors to effective leadership: humane and participative. Two were culture-sensitive impediments to effective leadership: autonomous and self-protective. Internal consistency and interrater reliability, computed by using a linear composite reliability formula (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994), displayed acceptable level of these scales – average internal consistency reliability = .84, and average interrater reliability = .95 (House et al., 2004, p. 136). And the countries were also placed into bands (high A – low D) in such a way, that their scores within the same band were statistically not significantly different from each other.

Within the GLOBE research we operationally measured the Russian cultural and leadership profile by assessing questionnaire responses from 450 middle managers in three industries (telecommunications, food processing, and financial services) with respect to (a) the values they endorse and (b) reports of practices of entities in their societies.

The main GLOBE survey was conducted in Russia in 1996-1998. Responses were received from 450 managers in food processing, telecommunication, and banking/finance, 150 managers from each industry. These managers represented different parts of the country – Far East, Siberia, the Urals, Southern and Northern Russia, and large cities of Central Region. The average age of respondents was 38.8 years, and the gender composition of the sample was 61.7% men and 38.3% women. The average employment profile of managers was as follows: number of years employed – 16.8 years, management experience – 7.4 years, and employment in current organization – 8.6 years. Forty percent were members of professional organizations, 15% were actively involved in trade and industry associations, and 5% had jobs in multinational corporations. Surveyed managers worked in production and engineering (42%), administration (28%), sales and marketing (15%), human resource management (8%), R&D (5%), and in planning and other functions (2%). The average educational level (15.5 years) of respondents was very high. The university/college background was 61% technical and 39% were in economics, planning, and finance. Twelve percent of all respondents received some training in Western management concepts and techniques.

Russian CLT Profile

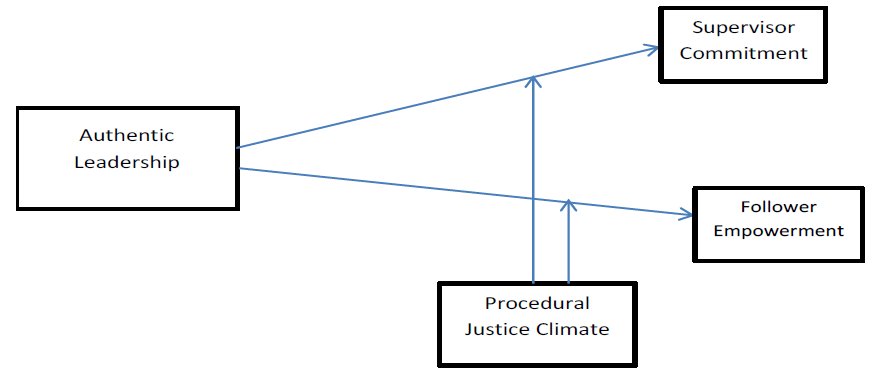

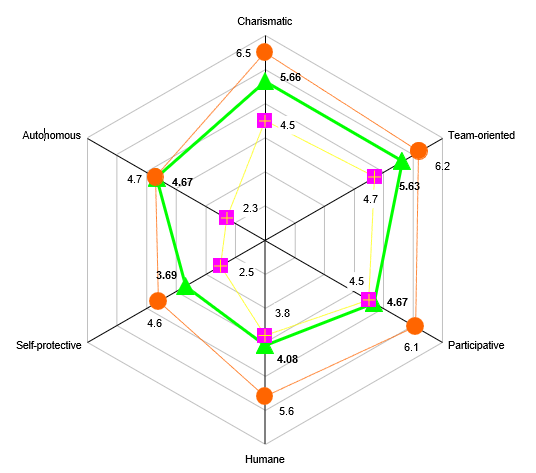

The overall profile of a Russian organizational leader on globally endorsed leadership dimensions is displayed in Figure 1. Appendix 1 and 2 contain quantitative data.

Charismatic/Value-Based Orientation

According to GLOBE, charismatic/value-based leaders have the ability to inspire and motivate others and facilitate high performance outcomes on the basis of firmly held core values. The aggregate score for universal positive leader attributes for Russia, summarized in Charismatic/Value-Based Leadership dimension, is relatively low (5.66) with rank 47 in band D. This was interpreted as only slightly contributing to outstanding leadership. One major reason for the low score on value-based leadership is the current societal transformation in Russia; many beliefs that dominated under Communism are eroding, and the value structure has been transforming radically in the last two decades. Different groups with different leadership philosophies and values are replacing the homogenous Soviet system. But transformative new values and beliefs that go far beyond technocratic or predatory philosophies have not yet emerged in the corps of business leaders and managers. The Russian score on this dimension is lower than the East European mean (5.74), lagging behind other countries in the cluster.

Figure 1. Global culturally endorsed implicit leadership (CLT) scores for Russia (circles – maximum mean, squares – minimum mean within 62 countries).

The first order dimensions for Charismatic/Value-Based Leadership display Visionary (6.07) as the prioritized dimension in considering effective leadership in Russia. Considering the relative vacuum of societal values and the high uncertainty regards the economy and society, the ability of leaders to formulate a vision on the organizational level is critical for the followers in the organization.

In the range of factors slightly contributing to effective leadership, we found Performance-Oriented (5.92), Inspirational (5.89), Decisive (5.86), and Integrator (5.72). Self-Sacrifice (4.28) had no impact on outstanding leadership. When we compared Russia’s scores and other countries’ scores on this second-order CLT dimension, we placed Russia in the A band on Decisive; in the B group on Visionary, Performance Orientation, and Integrity; and in the C band on Self-Sacrificial.

Team Orientation

Emphasis on effective team development and collective implementation of a common goal is central to the GLOBE interpretation of the second universal contributor to effective leadership. This second order dimension did not display an optimistic assessment of Russia, as well. Its Team-Oriented score was 5.63 with rank 46 in the C band. In the East European cluster it was lower than the group mean (5.88). While Russia has been long stereotyped as a collectivist country, GLOBE cultural scores display its transition to a more individualistic society. The vector of teamwork and group dynamics in such a society is not high or critically important to effective organizational leadership.

The first order scores prioritize the issues. While Administrative Competence is contributing to effective leadership in Russia (6.03), the other dimensions only somewhat contribute to effective leadership: Team-Oriented (5.15), Team Integrator (5.56), diplomatic (5.01), and Malevolent (reverse score 1.85). Russia’s comparative scores placed the country in the A band on the Administratively Competent dimension, but only in the C band on critical factors such as Team Orientation and Malevolence. On the other two dimensions, Diplomatic and Team Integrator, Russia fits the B band.

Humane Orientation

On this CLT dimension GLOBE research highlights supportive and considerate behavior that includes compassion and generosity. However, Russia’s low score (4.08) may be interpreted as having limited impact on outstanding leadership. This placed Russia with rank 60 into the D band. In the Eastern European cluster the score was lower than the group mean (4.67). In a transitional economy dominated by survival behaviors, with high corruption and bureaucracy, humanistic values exist in a limited number of companies that emphasize socially responsible philosophies.

First order dimensions related to this global CLT dimension are Modesty and Humane Orientation. In the case of Russia, the score on the former was 4.25 (no visible impact on effective leadership) and on the latter was 3.92, which slightly inhibits outstanding leadership. Both scores placed Russia into C band on these first order dimensions.

Participative Orientation

Involving others in making and implementing decisions, according to GLOBE, universally contributes to effective leadership. The Russian score on this dimension, however, is very low (4.67), placing the country in the D band. Within the Eastern European cluster, the Russian score was also lower than the group mean (5.08). Two major reasons support these findings. First, vertical structures and authoritarian decisions are effective in modern transitional Russia. Second, many successful Russian business networks depend on personal connections with bureaucracy and/or find themselves under the control of cruel criminal structures that leave no space for open, reciprocal, and trustful interaction and participation in decision-making.

Two first order dimensions explain contribution to Participative orientation. One was the high Autocratic score (4.16, reverse score). It placed Russia into A band and did not contribute to effective leadership. The other was Non-Participative (2.82, reverse score). Its relative value inhibiting from effective leadership was also high (B band). Hence, participation did not play an important role in defining effective leadership.

Autonomous

The second order dimension, Autonomous, displays independent and individualistic leadership. Many Russian business leaders emphasize their uniqueness and their autonomous performance. The score on this CLT (4.63) placed the country in band A. The first-order dimension score (Autonomous, 4.04) explained this CLT as inhibiting outstanding leadership. In the Eastern European cluster the Russian score was higher than the group mean (4.20).

Self-Protective

This CLT dimension corresponds to universal negative leadership attributes and focuses on ensuring the safety and security of the individual. In the case of Russia, this culture-sensitive impediment slightly negatively contributes to effective leadership. The Self-Protective score for Russia (3.69) placed the country in the A band with rank 17 and was about the same as the Eastern European mean (3.67). Since this was the reversed score, the negative impact on the universal CLT was quite visible.

The Self-Protective score is based on several first order dimension factors. Status Conscious (4.75) had no impact, and Conflict Inducer (3.90) had minimum influence on effective leadership. The other first order dimensions somewhat inhibiting people from being outstanding leaders were: Self-Centered (2.48), Face Saver (2.67), and Procedural (2.98).

On the comparative frame Russia found itself in B bands on Status Conscious, Self- Centered, and Conflict Inducer; in C band on Face Saver; and in D band on Procedural. The very low score on the Procedural dimension indicates that being procedural is likely to be a greater inhibitor from effective leadership in Russia than in most countries included in the GLOBE sample.

Conclusions

This research shed light on the current profile of organizational leadership in Russia. The GLOBE project was one of the first major attempts to collect an empirical data set on Russian leadership and culture and to rely on internationally recognized and reliable research methods. The findings presented herein seem to have quite important implications for both researchers and practitioners.

The comparative analysis on the GLOBE cultural scales showed contemporary Russia as having several extreme scores: very low in Uncertainty Avoidance, Future Orientation, Performance Orientation, and Humane Orientation; and very high in Power Distance. In particular, in a behavioral set of findings, extremely low Uncertainty Avoidance could be considered favorable for entrepreneurship activities unless one links it to the very low Future Orientation. This can be interpreted as a lack of vision in management and entrepreneurship and as a primary focus on survival and short-term business development. Low Performance Orientation makes it difficult to encourage managers to focus on continuous improvement and learning. Low ranking on Humane Orientation raises doubts about long-term investments in human resources. High Power Distance indicators explain the tough bureaucratic measures in crisis management and in restructuring enterprises and industries (Grachev, 2004).

In terms of global CLT dimensions Russia displays a clear picture of what makes its current leadership effective. Relatively more important attributes are Visionary and Administrative Competency. They are followed by Decisive, Performance Orientation, and Inspirational. Integrity, Team Integration, Collaborative, and Diplomatic somewhat contribute to outstanding leadership. At the same time Self-Sacrifice, Modesty and Human Orientation, Status Consciousness, and Conflict Inducer do not make a difference.

Our GLOBE results suggest that universal positive leadership attributes such as Charismatic/Value-Based Leadership (visionary, decisive, and inspirational) and Team Oriented Leadership are considered as slightly contributing to outstanding leadership in Russia. The latter mainly means to be administratively competent and collaborative oriented. However, the level of such influence is much lower than in most other countries. The other two dimensions that nearly universally contribute to leadership – Participative and Humane orientation – have only limited impact in Russia. What matters is a good “image” (linked to success competency and personal and social recognition) and acting as a “facilitator” (attract people, settle disputes, and control the situation) which seems to be the Russian manifestation of Participative Leadership. Humane Orientation is seen as relatively neutral to outstanding leadership whereas status consciousness and conflict inducing behaviors (Self-Protective leadership) are positively endorsed. Universal negative leadership attributes such as Self-Protective and Autonomous are relatively important in inhibiting effective leadership. For an outstanding leader in Russia, Autonomous leadership (individualistic, independent, and unique) is linked to “action-oriented” leadership endorsed in Russia (act with no hesitation, real fighter, enduring, and self-sacrificial).

Summarizing these findings, the paper displays the profile of an administratively competent manager, capable of making serious decisions and inspiring his/her followers to meet performance targets. To some extent he/she relies on teams and, through diplomatic and collaborative moves, succeeds in integrating efforts of his/her members. However, in his/her actions there is not much interest in humane orientation to others or modesty in personal behavior. He/she may sacrifice a lot and does not care about saving face. Status is not very important to the Russian organizational leader. Altogether one may consider that Russia is seeking its own way for effective leadership concepts and practices.

*The authors acknowledge participation of Boris Rakitski (Institute of Perspectives and Problems of the Country, Moscow, Russia) and Nikolai Rogovsky (International Labor Organization, Geneva, Switzerland) in GLOBE data collection and appreciate their conceptual insights that helped to finalize this paper.

* The authors served as GLOBE Country Investigators and conducted other GLOBE-related research on leadership. In particular, they contributed to the earlier research that explored leadership in 22 countries and further attested to the existence and importance of a CLT profile (Den Hartog et al., 1999). This research confirmed that attributes of charismatic-transformational leadership are universally endorsed as contributing to outstanding leadership. The other research highlighted cultural and leadership predictors of corporate and social responsibility of top management in 15 countries (Waldman et al., 2006).

About the Authors

Mikhail V. Grachev is associate professor of management at Western Illinois University and adjunct professor of management at the University of Iowa. He served as university faculty in the United States, France, Japan, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Russia; and focused research on international dimensions of organizational behavior and strategy. He is country co- investigator in the multinational cross-cultural research project GLOBE.

Grachev, Mikhail V., Associate Professor of Management

Western Illinois University 3561 60th Street Moline, Il 61265, USA

Email: mv-grachev@wiu.edu

Mariya A. Bobina is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her business competencies are based on practical experience as senior financial officer in the aircraft industry and as consultant to a number of international organizations and companies in the energy sector. She is country co-investigator in the multinational cross-cultural research project GLOBE.

Reference

Ageev, A., Gratchev, M., & Hisrich, R. (1995). Entrepreneurship in the Soviet Union and Post- Socialist Russia. Small Business Economics, 7(5), 365-376.

Bakacsi, G., Takacs, S., Karacsonyi, A., & Imrek, V. (2002). Eastern European cluster: Tradition and transition. Journal of World Business, 37, 69-80.

Chaadaev, P. (1991). Philosophical works of Peter Chaadaev. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publilshers.

Den Hartog, D., House, R., Hanges, P., Ruiz-Quantanilla, S., Dorfman, P., & GLOBE associates. (1999). Culture-specific and cross-culturally generalizable implicit leadership theories: Are attributes of charismatic/transformational leadership universally endorsed? Leadership Quarterly, 10(12), 219-256.

Dunnette, M., & Hough, L. (Eds.). (1991). Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Elenkov, D. (1997). Differences and similarities in managerial values between US and Russian managers. California Management Review, 40, 133-156.

Gratchev, M. (2001). Making the most of cultural differences. Harvard Business Review, October, 28-30.

Grachev, M. (2004). Cultural attributes of Russian management. Advances in International Management, 15, 159-177.

Gratchev, M., & Hisrich, R. (2001). The ethical dimensions of Russian and American entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 8(1), 5-18.

Guroff, G., & Carstensen, F. (Eds.). (1983). Entrepreneurship in Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Cultures consequences. International differences in work-related values. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

House, R., Hanges, P., Ruiz-Quintanilla, S., Dorfman, P., Javidan, M., Dickson, M., Gupta, V., et al. (1999). Cultural influences on leadership and organizations: Project GLOBE. In W. Mobley, M. Gessner, & V. Arnold (Eds.), Advances in global leadership. Stamford, CT: JAI Press, 171-233.

House, R., Wright, N., & Aditya, R. (1997). Cross-cultural research on organizational leadership. A critical analysis and a proposed theory. In P. Ch. Earley & M. Erez (Eds.). New perspectives on international industrial/organizational psychology. San Francisco: Lexington Press.

Huntington, S. (1993). The clash of civilizations? Foreign Affairs, 72(3), 22-49.

Kats de Vries, M. (2000). A journey into the “Wild East”: Leadership style and organizational practices in Russia. Organizational Dynamics, 28(4), 67-81.

Kluchevskii, V. (1904). Kurs Russkoi istorii. [The course in Russian history]. Moscow: Sinodalnaya Tipografiya.

Kluckhohn, F., & Strodtbeck, F. (1961). Variations in value orientation. New York: HarperCollins.

McClelland, D. (1985). Human motivation. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

Michailova, S. (2000). Contrasts in culture: Russian and Western perspectives on organizational change. The Academy of Management Executive, 14(4), 99-112.

Mikheyev, D. (1987). The Soviet mentality. Political Psychology, 8(4), 491-523. Naumov, A. (1996). Hofstedovo Izmerenie Rossii [Hofstede’s dimension of Russia]. Menedzhment, 3, 70-103.

Naumov, A., & Puffer, S. (2000). Measuring Russian culture using Hofstede’s dimensions. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 49(4), 709-718.

Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory. NY: McGraw-Hill.

Puffer, S. (Ed.) (1992). The Russian management revolution: Preparing managers for the market economy. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

Triandis, H. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Kats de Vries, M. (2000). A journey into the “Wild East”: Leadership style and organizational practices in Russia. Organizational Dynamics, 28(4), 67-81.

Waldman, D., Sully de Luque, M., Washburn, N., House, R., Bobina, M., Grachev, M., & GLOBE associates. (2006, forthcoming). Cultural and leadership predictors of corporate social responsibility values of top management: A GLOBE study of 15 countries. Journal of International Business Studies.

APPENDIX A

Global Culturally Endorsed Implicit Leadership (CLT) Dimensions: Russia in Cross-cultural Space

| Global Culturally Endorsed Implicit Leadership (CLT) Dimensions | First-order Dimensions | Russian Score | Score for Eastern European Cluster | Range for Mean Values for 62 Societal Cultures |

| Charismatic/Value-based (universal contributor to effective leadership) | Visionary, Inspirational, Self- sacrifice, Integrity, Decisive, Performance oriented | 5.66 | 5.74 | 4.5 – 6.5 |

| Team Oriented (universal contributor to effective leadership) | Collaborative team orientation, Team integrator, Diplomatic, Malevolent (reverse score), Administratively competent | 5.63 | 5.88 | 4.7 – 6.2 |

| Participative (culture-sensitive contributor to effective leadership) | Autocratic (reverse score), Non-participative (reverse score), Delegator | 4.67 | 5.08 | 4.5 – 6.1 |

| Humane (culture-sensitive contributor to effective leadership) | Modesty, Humane orientation | 4.08 | 4.67 | 3.8 – 5.6 |

| Self-protective (culture-sensitive impediments to effective leadership) | Self-centered, Status conscious, Conflict inducer, Face saver, Procedural | 3.69 | 3.67 | 2.5 – 4.6 |

| Autonomous (culture-sensitive impediments to effective leadership) | Individualistic, Independent, Autonomous, Unique | 4.67 | 4.20 | 2.3 – 4.7 |

APPENDIX B

Summary of First-order Leadership Dimensions for Russia

| Leadership Dimension | Indicator | Group ranking (band) | Leadership Dimension | Indicator | Group ranking (band) |

| Performance Orientation | 5.92 | B | Procedural (formerly bureaucratic) | 2.98 | D |

| Autocratic | 4.16 | A | Administratively Competent | 6.03 | A |

| Modesty | 4.25 | C | Self-centered | 2.48 | B |

| Charismatic III (Self Sacrificial) | 4.28 | C | Autonomous (Formerly Individualistic) | 4.04 | A |

| Team I: Collaborative (Team Orientation) | 5.15 | C | Status Consciousness | 4.75 | B |

| Decisive | 5.86 | A | Charismatic II (Inspirational) | 5.89 | C |

| Diplomatic | 5.01 | B | Malevolent | 1.85 | C |

| Face-saver | 2.67 | C | Team II: Team Integrator | 5.65 | B |

| Humane Orientation | 3.92 | C | Conflict Inducer | 3.90 | B |

| Charismatic I (Visionary) | 6.07 | B | Non-Participative | 2.82 | B |

| Integrity | 5.72 | C |