The Nathan Factor: The Art of Speaking Truth to Power

Seemingly within today’s organizational cultures, the adage “the truth hurts” has hindered leaders from listening and intimidated followers from articulating. This has ultimately stalled corporations from maximizing their potential. The questions become: Where has the courage to stand up for and to flawed leadership gone? What does scripture have to say about this issue and does the text offer practical applications to the reader? Within this article, such questions are confronted as the life of the prophet Nathan, as recorded in 2 Samuel, is analyzed. This editorial contextually walks with the prophet as he navigates through five critical moments within the text. This journey consequently gleans lessons from this courageous follower and articulates a historical biblical methodology to relevantly speak truth to power in today’s context.

A cursory glance at today’s organizational cultures suggests that various entities are thirsty for personalities that would dare speak the truth to power. Military branches coveted such change agents when the Abu Ghraib prison scandal emerged from the shadows of Baghdad. The people affiliated with various businesses like Enron, retrospectively longed for such a person as they watched stocks crumble before their eyes. After the Challenger exploded, the nation tragically wondered why NASA or the Thiokol engineers did not have the moral vigor to embrace the adage of not being “afraid to challenge the pros, even in their own backyard.”1

The overall intent of this article is to wrestle with the questions: What happens when power disregards truth? Is there a systematic method to speaking truth to power and what happens to both the messenger and the message after truth has been delivered? This deliberation provides an exegesis of five biblical pericopes. First, 2 Samuel 7:1-3 focuses on the probable leadership trait that empowered Nathan to become the next adviser to the king. Second, 2 Samuel 7:4-12 focuses on the driving force of this prophet—spirituality. Third, 2 Samuel 12:1-14 highlights the courageous followership of Nathan and illustrates how he skillfully spoke the truth to power. Fourth, 1 Kings 1:10-14 explores the emotional intelligence of the prophet as he navigated through negative political realities. Fifth, 2 Chronicles 9:29 explores the management capabilities of Nathan that consequently made him a credible asset within the king’s court.

I. The Prelude to the Position

Scholars are baffled over the logistics of how Nathan emerged into the position of being a prophet.2 Some suggest that his political abilities enabled him to succeed Samuel as the next advisor.3 While others speculate that his poetic talent ushered him into prominence.4 Bodner additionally asserts that biblical literature is relatively limited and consequently silent due to the lack of elaboration within the text.5 Aside from the providence of God, perhaps another element may contribute to this dialogue. Consider 2 Samuel 7:1-3:

1 Now when the king was settled in his house, and the LORD had given him rest from all his enemies around him, 2 the king said to the prophet Nathan, “See now, I am living in a house of cedar, but the ark of God stays in a tent.” 3 Nathan said to the king, “Go, do all that you have in mind; for the LORD is with you.”

This portion of scripture introduces Nathan to the reader for the first time during a season when David was enjoying a level of peace and abundant prosperity. Contextually speaking, David had no other advisors after the death of the beloved prophet Samuel (1 Sm 28:3). As such, the role of the consultant to the king was vacant.

The question becomes: How did Nathan secure his position and earn the confidence of the king in such a short span of time? I would contend that the confidence the king had in Nathan was a direct result of this prophet’s nature. Cornwall and Smith assert that biblical “name(s) have meaning. So much so, that sometimes when God changed the nature of a person He also changed his or her name.” For example, the Hebrew root of the name Nathan (ַַתן ָנ) can be transliterated “to give.”6 Harris, Archer, and Waltke suggest that the connotation of ַתן ָנ could range from anything from “physically handing a present, reward, person, or document to another to the less tangible granting or bestowal of blessing, compassion, permission, and the like.”7

I would argue that Nathan epitomized the essence of his name and served (gave of himself) his way into the king’s court. To reiterate, the text does not expound upon the particulars of how Nathan emerged as the king’s advisor but one can formulate a theory based on the Hebrew tradition of a name. For purposes of this article, we will refer to this idea as Nathan’s theory of position. To recap, this theory asserts that Nathan’s giving mannerism or servant nature escorted him into the position of being next to the king.

Contemporary scholarship would categorize both the essence of his name and the attributes thereof as servant leadership. Servant leadership has a noteworthy definition. Greenleaf asserts:

The servant-leader is servant first…….. It begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. The conscious choice may bring one to aspire to lead. That person is sharply different from one who is leader first, perhaps because of the need to assuage an unusual power drive or acquire material possessions. The difference manifests itself in the care taken by the servant-first to make sure that other people’s highest priority needs are being served. The best test, and difficult to administer, is this: Do those served grow as persons? Do they, while being served, become healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, more likely themselves to become servants? And, what is the effect on the least privileged in society? Will they benefit or at least not be further deprived?8

Spears maintains that servant leadership essentially possesses ten key elements. They include:

- Listening receptively to what others have to say

- Acceptance of others and having empathy for them

- Foresight and intuition

- Awareness and perception

- Having highly developed powers of persuasion

- An ability to conceptualize and to communicate concepts

- An ability to exert a healing influence upon individuals and institution

- Building community in the workplace

- Practicing the art of contemplation

- Recognition that servant leadership begins with the desire to change oneself 9

Spears notes, “Once that process has begun, it then becomes possible to practice servant-leadership at an institutional level.”10

The pericope at hand can demonstrate that this man of God displayed the above attributes and further amplifies Nathan’s theory of position. For example, the text shows Nathan listening receptively to David and offering empathy. Verse 1 says, “The king said to the prophet Nathan.” Nathan’s foresight, awareness, ability to persuade, and to communicate concepts as well as his healing influence points toward his title of being a “prophet.” Moreover, his discipline of contemplation and his brokenness are additional traits conducive of walking in the office of a “seer.”11

Maxwell frames this theory of Nathan’s position resulting from servant leadership as the effect of the law of sacrifice. The premise of this construct is “a leader must give up in order to go up.”12 More specifically, one must constantly and unselfishly give (which is the meaning of the name “Nathan”) of oneself to an organization. Moreover, Maxwell asserts, “If leaders have to give up, then they have to give up more to stay up.”13 Perhaps Nathan became the next consultant to the king simply because he was the only one at that time that dared to unselfishly give of himself when his audience was only God?

Nathan’s theory of position can empower the reader with principles on how to receive that promotion and become an advisor to our figurative “kings.” First, we must allow the principles of servant leadership to become a part of our being. So much so that others will rename our style of influence from narcissism to Nathan—one who gives. Narcissism can be defined as “an extreme need for esteem, need for power, weak self-control and indifference to the needs of others.”14 Second, Greenleaf’s sentiments of the servant leader being a servant first must remain in the forefront of our minds. Such a posture may keep us grounded in the fact that ultimately, similar to Nathan, we are serving an audience of one—God. Finally, we must trust that God is faithful to execute his promises to the person that would dare to give. Luke 6:37-3815 articulates it best:

37 Don’t pick on people, jump on their failures, criticize their faults—unless, of course, you want the same treatment. Don’t condemn those who are down; that hardness can boomerang. Be easy on people; you’ll find life a lot easier. 38 Give away your life; you’ll find life given back, but not merely given back—given back with bonus and blessing. Giving, not getting, is the way. Generosity begets generosity.

II. Nathan’s Spirituality in the Workplace

The second critical component of a person that would dare to speak truth to power is spirituality in the workplace. This emerging concept of spirituality in the workplace has a plethora of meanings. Freshman asserts, “Not any one, two or even three things can be said about spirituality in the workplace that would include the universe of explanations.”16 He adds, “There is no one answer to the question, ‘What is spirituality in the workplace?’ Definitions and applications of spirituality in the workplace are unique to individuals. One must be careful not to presuppose otherwise. Therefore when planning any group or organizational intervention around the topic, again the suggestion is made to derive definitions and goals from the participants themselves.”17

Building upon Freshmen’s insight and gleaning from the ensuing pericope, I contend that Ashar and Lane-Maher’s understanding of spirituality in the workplace is applicable. They assert:

Spirituality is an innate and universal search for transcendent meaning in one’s life. In addition, although it can be expressed in various ways, we submit that spirituality at work involves some common behavioral components. Above all, it involves a desire to do purposeful work that serves others and to be part of a principled community. It involves a yearning for connectedness and wholeness that can only be manifested when one is allowed to integrate his or her inner life with one’s professional role in the service of a greater good.18

Moreover, Marques, Dhiman, and King add that workplace spirituality has nineteen distinct traits (which may be evident in the life of Nathan). They include “ethics, truth, believe in God, respect, understanding, openness, honesty, being self-motivated, encouraging creativity, giving to others, trust, kindness, team organization, few organization barriers, a sense of peace, a pleasing workplace, interconnectedness, encouraging diversity and acceptance.”19

Second Samuel 7:4-17 highlights Nathan’s spirituality in the workplace and may demonstrate his sincere desire to be linked to the Holy while operating within his professional role. Observe:

4 But that same night the word of the LORD came to Nathan: 5 “Go and tell my servant David: ‘Thus says the LORD: Are you the one to build me a house to live in? 6 I have not lived in a house since the day I brought up the people of Israel from Egypt to this day, but I have been moving about in a tent and a tabernacle. 7 Wherever I have moved about among all the people of Israel, did I ever speak a word with any of the tribal leaders of Israel, whom I commanded to shepherd my people Israel, saying, “Why have you not built me a house of cedar?”’

8 “Now therefore thus you shall say to my servant David: ‘Thus says the LORD of hosts: I took you from the pasture, from following the sheep to be prince over my people Israel; 9 and I have been with you wherever you went, and have cut off all your enemies from before you; and I will make for you a great name, like the name of the great ones of the earth. 10 And I will appoint a place for my people Israel and will plant them, so that they may live in their own place, and be disturbed no more; and evildoers shall afflict them no more, as formerly, 11 from the time that I appointed judges over my people Israel; and I will give you rest from all your enemies. Moreover the LORD declares to you that the LORD will make you a house. 12 When your days are fulfilled and you lie down with your ancestors, I will raise up your offspring after you, who shall come forth from your body, and I will establish his kingdom. 13 He shall build a house for my name, and I will establish the throne of his kingdom forever. 14 I will be a father to him, and he shall be a son to me. When he commits iniquity, I will punish him with a rod such as mortals use, with blows inflicted by human beings. 15 But I will not take my steadfast love from him, as I took it from Saul, whom I put away from before you. 16 Your house and your kingdom shall be made sure forever before me; your throne shall be established forever.’” 17 In accordance with all these words and with all this vision, Nathan spoke to David.

The above passage dramatizes Nathan’s intimate bond to the Holy. I contend, this relationship that God had with Nathan enabled this prophet to be an effective corporate man. Such spirituality made Nathan teachable, ethical, and more inclined to strive for excellence. Bodner suggests that though the passage under investigation is catered to David, the tone and style of the spiritual message is also directed at Nathan. Additionally, Bodner makes four bold assertions that consequently amplify Nathan’s strong sense of spirituality. He states:

The complexity of this speech in 7:3-16 is designed, among other things, to communicate four points to Nathan. First, the prophet is rebuked for blithely encouraging David “Go, do all that is in your heart; for the LORD is with you.” The rather acerbic edge to the divine words illustrates that the LORD is not pleased with either Nathan or David’s presumption, and unlike the two of them, speaks of “building a house” without any indirection whatsoever. Second, the prophet receives something of a theological education. Eslinger successfully draws attention to the rhetorical subtleties of this passage. However, one could take it a step further and suggest that part of the rhetorical thrust is aimed at educating the prophet. Third, Nathan receives instructions that are minutely specific—even to the point whereby indirect discourse is employed. This is designed to show the prophet how important this message is, and that it is imperative that he deliver it flawlessly. In other words he is being instructed not to tell the king simply to “Go, do all that is in your heart,” but rather to speak in consonance with the divine instruction. Fourth, Nathan the prophet is given insight into the future promises to David’s house.20

Bodner’s observation points toward some critical elements of spirituality. First, the notion of Nathan being “rebuked for blithely encouraging David” possibly points toward this prophet’s ability to be open.21 This facet of openness or transparency can be a catalyst to organizational trust. This intangible element, according to Covey, can effortlessly increase the speed (effectiveness) of an entity and lower overall cost.22 I assert that the ability to be open to receive correction from God is not only a sign of wisdom (Prv 3:11-12) but a critical element in decision making (Prv 3:6).

The idea of Nathan receiving “something of a theological education,” secondly points toward Marques et al. workplace spirituality trait of understanding. According to the Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, understanding can be defined as, “the power of comprehending or the capacity to apprehend general relations of particulars.”23 This trait undeniably empowered the prophet to become relevant and competent in his deliberations. In an era of technology and constant change, it would behoove the person that would serve within the king’s court to commit to the process of lifelong learning.

Thirdly, Nathan demonstrated the spirituality workplace mannerism of the “removal of barriers.”24 This concept can be inclusive of addressing and implementing new systems into an organization for the purposes of process improvement.25 To reiterate, Bodner suggests that “Nathan receives instructions that are minutely specific—even to the point whereby indirect discourse is employed.”26 I would contend that such specific discourse from God to Nathan was a “divine” attempt to implement a system (word from the Lord not an opinionate utterance from the prophet) that would proactively debunk barriers that could potentially hinder organizational productivity.

The fourth spirituality workplace trait of Nathan is the encouragement of creativity. According to the Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, creativity can be defined as, “the quality of being creative or the ability to create.”27 According to Bodner’s exegesis, “the prophet is given insight into the future promises to David’s house.”28 I contend that such an insight enabled both David and Nathan to recast a vision large enough for generations yet to come, to grow. As such, according to Yukl, this construct is essential to corporations if they are to lead followers through change.29

In summary, I argue that Nathan’s fourfold attributes of spirituality in the workplace vested him with a sense of ethical authority. His integrity (as a result of the above spirituality) may have established him to be a person of high corporate creditability. Such creditability empowered both God and David to believe that Nathan was trustworthy enough to be a steward over the deliberations of the team. Perhaps Nathan’s example of workplace spirituality (being transparent, teachable, removing of barriers, and encouraging creativity) can be considered as a new paradigm for cultivating corporate creditability.

III. The Courage to Declare, “You are the man!”

Thus far we have made a case that servant leadership escorted Nathan into power and his spirituality in the workplace gave him a tremendous amount of corporate credibility. Those two leadership constructs set the stage to introduce to the reader the mechanics behind Nathan’s ability to speak truth to power. Within this section of the article, an exegesis of 2 Samuel 12:1-15 is offered, the construct of courageous followership are engaged, key terms are defined (i.e., parable, speaking truth to power), and practical steps to courageously declare to your leader, “You are the man!” are articulated.

Second Samuel 12:1-15 essentially captures what most readers think of when the name Nathan is invoked. Notice his claim to fame:

And the LORD sent Nathan to David. He came to him, and said to him, “There were two men in a certain city, the one rich and the other poor. 2 The rich man had very many flocks and herds; 3 but the poor man had nothing but one little ewe lamb, which he had bought. He brought it up, and it grew up with him and with his children; it used to eat of his meager fare, and drink from his cup, and lie in his bosom, and it was like a daughter to him. 4 Now there came a traveler to the rich man, and he was loath to take one of his own flock or herd to prepare for the wayfarer who had come to him, but he took the poor man’s lamb, and prepared that for the guest who had come to him.”

5 Then David’s anger was greatly kindled against the man. He said to Nathan, “As the LORD lives, the man who has done this deserves to die; 6 he shall restore the lamb fourfold, because he did this thing, and because he had no pity.”

7 Nathan said to David, “You are the man! Thus says the LORD, the God of Israel: I anointed you king over Israel, and I rescued you from the hand of Saul; 8 I gave you your master’s house, and your master’s wives into your bosom, and gave you the house of Israel and of Judah; and if that had been too little, I would have added as much more. 9 Why have you despised the word of the LORD, to do what is evil in his sight? You have struck down Uriah the Hittite with the sword, and have taken his wife to be your wife, and have killed him with the sword of the Ammonites. 10 Now therefore the sword shall never depart from your house, for you have despised me, and have taken the wife of Uriah the Hittite to be your wife. 11 Thus says the LORD: I will raise up trouble against you from within your own house; and I will take your wives before your eyes, and give them to your neighbor, and he shall lie with your wives in the sight of this very sun. 12 For you did it secretly; but I will do this thing before all Israel, and before the sun.”

13 David said to Nathan, “I have sinned against the LORD.” Nathan said to David, “Now the LORD has put away your sin; you shall not die. 14 Nevertheless, because by this deed you have utterly scorned the LORD, the child that is born to you shall die.” 15 Then Nathan went to his house.

I would contend that this pericope essentially has five major components. First, the entrance of Nathan in verse 1, “And the Lord sent Nathan to David.” Second, verses 1b–12 highlight the mechanics of how Nathan confronted David. Third, verse 13a points toward David’s disposition when it says, “David said to Nathan, ‘I have sinned against the Lord.’” Fourth, verse 13b–14 demonstrates Nathan’s ability to engage in process consulting. Finally, verse 15 highlights Nathan’s exit strategy upon speaking truth to power.

Different scholars and practitioners are utilized to define the phrase speaking truth to power. Powell refers to this concept as not being “afraid to challenge the pros, even in their own backyard.”30 Chaleff frames this process simply as the courage to challenge.31 Chaleff further explains that here one “gives voice to the discomfort they feel when the behaviors or policies of the leader or group conflict with their sense of what is right. They are willing to stand up, to stand out, to risk rejection, to initiate conflict in order to examine the actions of the leader and group when appropriate.”32

This article embraces Yulk’s definition of power. He states that “the term power is usually used to describe the absolute capacity of an individual agent to influence the behavior or attitudes of one or more designated target persons at a given point in time.”33 Hence, for the purposes of this article, the term speaking truth to power refers to a person not being afraid to challenge those agents that influence the behavior or attitudes of one or more designated target persons at a given point in time, even in their own backyard.

How to Approach Problematic Power

Often times approaching a powerful person with leadership issues can invoke a creative tension. Scott amplifies this point in writing, “90 percent of workers are afraid to confront the boss. Getting fired isn’t the biggest concern. Instead people worry about being labeled troublemakers, being perceived as not being team players, suffering salary loss or career derailment or damaging future relations with the boss.”34

In light of Scott’s insight, Chaleff asserts that one must find equal footing with the leader if the “approach” is to be received and such stereotypes defused. I define approach as the methodology in which a follower comes into the presence of a leader for the expressed purposes of speaking truth to power. Chaleff explains, “Followers usually cannot match up to a leader’s external qualities, such as the trappings of formal power, and must find their equal footing on intellectual, moral or spiritual ground.”35

The first facet within the genre under investigation illustrates how Nathan acquired equal footing with David. To reiterate, verse 1a indicates, “And the Lord sent Nathan to David.” The term “sent” highlights to the reader how Nathan was able to move past David’s external qualities and make a receivable entrance. According to Enhanced Strong Lexicon, the Hebrew word “sent” ַלחשָׁ [shalach /shaw·lakh/] has several translations, including “to send off or away or out or forth . . . to let go or set free.”36

This notion of sending forth and setting free lays a threefold framework that’s essential to level the playing field between a follower and a leader. First, is divine intervention. Though the text does not specify, I first assert that the Lord was behind the scenes preparing the heart of David for Nathan. This assertion is not made in a vacuum. On the contrary, it’s based on the same Hebrew word “sent.” This term was also used when God commissioned Moses to speak truth to power in Egypt (Ex 3:14). Within that context, God hardened and softened the heart of Pharaoh long before Moses spoke any truth. In like manner, I believe the Lord was turning the heart of David before Nathan even interacted. Proverbs 21:1 supports such logic, “The king’s heart is a stream of water in the hand of the LORD, he turns it wherever he will.”

The second element that must drive a person that would dare to speak truth to power is love. To reiterate, the text indicates that, “And the Lord sent Nathan.” From a Christian’s theological lens, it is understood that God is love (1 Jn 4:8). Thus, one can argue that verse 1a can possibly be interpreted as, “And Love sent Nathan.” Winston contends that the Greek language outlines four forms of love:

The first type of love, eros, is sexual love . . . the second type of love, phileo (is) brotherly love……………………. The third type of love, agape, is a self-sacrificing love that references total commitment even unto death…….. A fourth type of love—agapao love. This Greek word refers to a moral love, doing the right thing at the right time for the right reason.37

Nathan’s agenda was to do the right thing at the right time for the right reason. I argue that the right thing required Nathan to think in a loving manner. This form of love requires one to challenge how one thinks toward others in the workplace. Winston asserts, “Leaders must then think in morally loving terms toward employees before they act.”38 The alternative of not embracing such a paradigm shift is to be motivated by either selfish ambition or hatred.39 This posture of being motivated by selfishness can possibly sabotage the message of the truth teller even before it’s delivered.

The final element that’s essential to the approach of one speaking truth to power is one’s attire. Freeman maintains, “The custom of biblical prophets was to wear the proper clothing. Such clothing identified them to be the spokesperson of the Lord in the tradition of prophets before them.”40 I assert that since Nathan was a prophet, he embraced the same rituals. Bjorseth elaborates upon attire and declares, “A professional image—appearance and behavior—helps start the experience in the right vein since people decide 10 things about you within 10 seconds of seeing you.”41 Bjorseth continues by stating, “What one wears reveals eight things—self-esteem, self- respect, confidence, organizational skills, soundness of judgment, attention to detail, creativity and reliability.”42 It was as if Nathan was aware of Bjorseth’s posture on attire and proactively removed any barriers that may have derailed his message.

All in all, 2 Samuel 12:1a outlined three strategies for approaching power. First, one must make provisions for divine intervention and allow God to prepare the heart of a leader to receive the message. Second, the person that would dare speak truth to power should be motivated by a spirit of love. This mentality can better equip one in the sentiments of Winston, “to do the right thing at the right time for the right reason.”43 Third, it would be advantageous for one to dress for success. This gesture may proactively remove potential barriers that could distract from the message. Nathan embraced such techniques and consequently set the stage for him to wisely declare, “You are the man!”

It’s Not the What, It’s the How

Verses 1b–12 highlight a threefold methodology on how to speak truth to power.

Upon approaching King David, Nathan invoked an innovative way to confront the behavior of his leader. Chaleff refers to such ingenuity as “preparing a leader for feedback.”44 He cautions at this point, however, that:

There is little value in standing up and giving leaders feedback they cannot hear. The courageous follower’s role is to find ways leaders can receive the feedback they need. We can minimize defensiveness by prefacing our feedback with a defusing statement that conveys respect and reminds the leader of the value of honesty.45

Nathan’s technique of minimizing the defensiveness of David was with a parable. Copenhaver asserts, “A parable is a weapon of weakness…….. A parable, however, can get past the defenses of our own behavior and reach the inner court where there is agreement about what is right and what is wrong.”46 Nathan’s parable followed suit and defused the defensiveness of David as well as kept his leader in a position of power.

This notion of preparing the leader for feedback with questions or with a parable made it advantageous for David to connect at an ethical level.47 This second point of setting an atmosphere for the leader in the sentiments of Covey, to first understand, is a critical step before confrontation. David demonstrated he understood Nathan’s parable when he acknowledged with anger in verse 5b-6, “As the LORD lives, the man who has done this deserves to die; he shall restore the lamb fourfold, because he did this thing, and because he had no pity.”

Upon Nathan brilliantly preparing David for feedback with a parable and creating an atmosphere for the leader to understand, Nathan courageously spoke truth to power. Verses 7-12 outline the confrontation process.

7 Nathan said to David, “You are the man! Thus says the LORD, the God of Israel: I anointed you king over Israel, and I rescued you from the hand of Saul; 8 I gave you your master’s house, and your master’s wives into your bosom, and gave you the house of Israel and of Judah; and if that had been too little, I would have added as much more. 9 Why have you despised the word of the LORD, to do what is evil in his sight? You have struck down Uriah the Hittite with the sword, and have taken his wife to be your wife, and have killed him with the sword of the Ammonites.10 Now therefore the sword shall never depart from your house, for you have despised me, and have taken the wife of Uriah the Hittite to be your wife.11 Thus says the LORD: I will raise up trouble against you from within your own house; and I will take your wives before your eyes, and give them to your neighbor, and he shall lie with your wives in the sight of this very sun.12 For you did it secretly; but I will do this thing before all Israel, and before the sun.

The mechanics of speaking truth to power involved several components. First, Nathan helped David to see that he was indeed the source of the problem both in the parable and within his leadership. Second, Nathan specifically outlined the error of David’s ways. Third, Nathan articulated what would happen as a result of David’s poor decision making. Lastly, it must be noted that this entire process occurred privately. Hence, affirming the adage “praise in public and correct in private.”

Creating an Atmosphere for Transformation

This fourfold process of making the leader see that he is the source of the problem, specifically identifying his errors, projecting the consequences of poor decision making, and doing it privately helped David to transform. Verse 13 indicates that after this encounter, “David said to Nathan, ‘I have sinned against the LORD.’” Chaleff rightly states, “Transformation occurs most readily in an atmosphere of ‘tough love’—a genuine appreciation for the person and a steadfast stance against the behaviors that are detrimental to the person and the organization.”48

I assert that the ultimate goal of a person that dares to speak truth to power is not to destroy the person but rather to usher them to a place within themselves to want to change. The fruit of such a broken state is inclusive of taking personal responsibility, changing one’s thinking, righting wrongs, remaining teachable, and becoming accountable to someone else. This fruit can flourish within a garden that’s cultivated by tough love. Such was the case with David upon being confronted by Nathan, the king yielded the fruit of repentance and consequently wrote Psalm 51 as evidence.

The Road to Recovery

Verse 13b–14 reveals three steps to help a remorseful leader move down the road of recovery. Upon David acknowledging his wrong, “Nathan said to David, ‘Now the LORD has put away your sin.’” This portion of scripture first demonstrates the empathy of Nathan. Salvey and Mayer define empathy “as the ability to comprehend another’s feelings and re-experience them oneself.”49 They continue that at this place a person can stay in step with another’s emotions and can facilitate a leader’s growth.50 I argue that without the trait of empathy, Nathan could not have gone any further on the road of recovery with David.

The second point that this text highlights is the importance of offering forgiveness. Elwell argues that forgiveness includes, “Pardon, involving restoration of broken relationships; ceasing to feel resentment for wrongs and offenses. Primarily, forgiveness is an act of God, releasing sinners from judgment and freeing them from the divine penalty of their sin.”51 It was as if Nathan understood that in order for David to move on with his life, he had to experience God’s mercy in the midst of failure. Such mercy is often the hope needed in the sentiments of Maxwell, to motivate a leader to get up, get over it and get going.52

The final lesson one can glean from this portion of text is Nathan’s willingness to participate in the transformation process. Chaleff maintains, “If we wish to help a leader transform, we must ourselves be willing to participate in the process of transformation. We need to examine our own role in the relationship with the leader. That is the only role we potentially have full power to change. We need to notice what we potentially have full power to change.”53

In Nathan’s case, it was as if he fully understood his role and articulated, “you shall not die. Nevertheless, because by this deed you have utterly scorned the LORD, the child that is born to you shall die.” It must be noted that Nathan did not say he was resigning but implied that he was willing to stay with his leader (because he repented) even during dark times. I assert that this willingness to participate in the transformation process is the moral obligation of a follower upon speaking truth to power.

Nathan’s Exit Strategy

The question becomes: What does one do after one speaks truth to power? Verse 15 displays Nathan’s possible methodology, “Then Nathan went to his house.” The text does not indicate what the prophet specifically did once he arrived home or what he may have mused upon. Given the context of the situation, one can only speculate. I would venture to say that Nathan did three things—prayed for David, protected his confidentiality, and pondered how he would coach David through the storm.

First Timothy 2:1-3 indicates the importance of praying for leadership:

First of all, then, I urge that supplications, prayers, intercessions, and thanksgivings be made for everyone, 2 for kings and all who are in high positions, so that we may lead a quiet and peaceable life in all godliness and dignity. 3 This is right and is acceptable in the sight of God our Savior.

Though this is a New Testament principle, it was as if Nathan took this counsel to heart and immediately began to intercede for David. Perhaps the greatest gift one can give to a leader is the commitment to hold them up in prayer.

Second, I argue that Nathan held the confrontation process in strict confidentiality. Nessan defines this concept as, “the act of protecting from disclosure that which has been told under the assumption that it will not be revealed without permission.”54 When a person breaks the seal of confidentiality it can possibly destroy trust, hinder transformation, and marginalize a follower from speaking truth to power in the future.

Lastly, I believe Nathan took the time to ponder how he would coach David through the storm in the days ahead. Yukl indicates:

The primary purpose of executive coaching is to facilitate learning of relevant skills. Coaches also provide advice about how to handle specific challenges, such as implementing a major change, dealing with a difficult boss, or working with people from a different culture. Having a coach provides the unusual opportunity to discuss issues and try out ideas with someone who can understand them and provide helpful, objective feedback and suggestions, while maintaining strict confidentiality.55

Like any skill, one must meticulously think through strategies and plans in order to be effective. Such was the case with Nathan. Upon confronting the king I believe he went home and pondered his next steps.

Overview

Within this section of the article we explored Nathan’s pathway of speaking truth to power. First, the logistics of how to approach problematic authority was delineated. Namely, relying upon divine intervention, being motivated by love, and dressing for the occasion. Second a dialogue was engaged with regard to the mechanics of speaking truth to power. That included indirectly challenging with questions or parables, assuring the leader understands the gist of the questions/parable, and direct confrontation.

Third, it was emphasized that the ultimate goal of truth telling was not to destroy but to create a space for the leader to repent. Fourth, several steps were offered to the reader on how to help a leader recover, including being empathic, offering forgiveness, and being willing to participate in the transformation process. Finally, a threefold exit strategy was outlined—pray for the leader, hold the confrontation process in strict confidentiality, and ponder how one can coach a fallen leader through difficult times.

IV. Nathan’s Emotional Intelligence

First Kings 1:10-14 highlights the fourth undergirding element of a person that would dare speak truth to power—emotional intelligence. Consider the savvy ways of Nathan as he navigates through some problematic realities in verses 10-14:

But he did not invite the prophet Nathan or Benaiah or the warriors or his brother Solomon. 11 Then Nathan said to Bathsheba, Solomon’s mother, “Have you not heard that Adonijah son of Haggith has become king and our lord David does not know it?12 Now therefore come, let me give you advice, so that you may save your own life and the life of your son Solomon.13 Go in at once to King David, and say to him, ‘Did you not, my lord the king, swear to your servant, saying: Your son Solomon shall succeed me as king, and he shall sit on my throne? Why then is Adonijah king?’ 14 Then while you are still there speaking with the king, I will come in after you and confirm your words.”

Contextually speaking, this text places the reader at a moment when King David was old and near death. Adonijah decided to take advantage of the moment and appoint himself the next king without the endorsement of God, King David, or the prophet Nathan. This power play by Adonijah required a response if the organization were to be sustained.

I assert that Nathan’s response was laced with emotional intelligence. Mayer and Salovey suggest, “Emotional intelligence is the ability to perceive emotions, to access and generate emotions so as to assist thought, to understand emotions and emotional knowledge, and to reflectively regulate emotions so as to promote emotional and intellectual growth.”56 Holt and Jones add that emotional intelligence can be measured on the Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory. This indicator that was derived based upon nineteen years of research consists of five composite scales:

- Intrapersonal scales: Self-regard, emotional self-awareness, assertiveness, independence, self-actualization.

- Interpersonal scales: empathy, social responsibility, interpersonal relationships.

- Adaptability scales: reality testing, flexibility, problem solving.

- Stress management scales: stress tolerance, impulse control.

- General mood scales: optimism, happiness.57

I argue that Nathan would have done enormously well on the Bar-On Emotional Quotient Inventory. Verse 10 emphasizes Nathan’s possible intrapersonal disposition when it says, “But he did not invite the prophet Nathan or Benaiah or the warriors or his brother Solomon.” This lack of invitation not only of Nathan but others (i.e., King David, Solomon, others) may have invoked problematic emotions (i.e., anxiety or rejection) within the prophet. Such emotions propelled Nathan to be assertive and respond quickly.

His response outlined in verses 11-14 highlights Nathan’s interpersonal skills, his problem solving abilities, and how he effectively managed the stress of negative politics. First, he immediately found the key stakeholder (Bathsheba) and networked. I believe such networking would have been problematic if Nathan’s interpersonal skills were weak. Second, Nathan demonstrated a keen sense of problem-solving ability when he advised Bathsheba on how to address the king (see verses 13-14). Finally, Nathan maintained an overall demeanor of optimism and projected a strong sense of stress tolerance.

Needless to say, due to Nathan’s emotional intelligence the organization was able to defuse the agenda of a self-centered personality (see verses 28-53) and in the sentiments of Jim Welch, “put the right person in the right job.” As such, it would behoove corporations to abstract principles from Nathan and become more emotionally intelligent. I assert that Goleman was right when he said, “Having great intellectual abilities may make you a superb fiscal analyst or legal scholar, but a highly developed emotional intelligence will make you a candidate for CEO or a brilliant trial lawyer.” In the example of this article, a value added truth teller.

V. Nathan’s Management Skills

Second Chronicles 9:29 draws attention to the final influential component of an individual that would dare speak truth to power. According to Easton, the last biblical appearance of Nathan appears to be assisting David reorganizing public worship.58 The text declares, “And he set the Levites in the house of the LORD with cymbals, with psalteries, and with harps, according to the commandment of David, and of Gad the king’s seer, and Nathan the prophet: for so was the commandment of the LORD by his prophets.”

I believe that this text demonstrates Nathan to be a proficient manager. Kotter states, “Management seeks to produce predictability and order by (1) setting operational goals, establishing action plans with timetables and allocating resources; (2) organizing and staffing (establishing structure, assigning people to jobs); and (3) monitoring results and solving problems.”59 Nathan’s management skills were so proficient that his policies influenced the leadership of the fourteenth reigning King (Hezekiah) of Israel. Moreover, his ability to do things rightly literally wrote him into the history books. Consider 2 Chronicles 2:29a, “Now the rest of the acts of Solomon, first and last, are they not written in the book of Nathan the prophet.”

Based on the text under investigation, I believe that as one’s ability to do the right thing (management skills) elevates 60, so will organizational creditability. This trait possibly handed Nathan a megaphone to not only speak the truth but to influence others long after his era. Maxwell refers to this construct as the law of E.F. Hutton. That is, due to one’s creditability, competency and integrity others stop and listen.61 Without question, Nathan was a manager par excellent.

XII. Discussion

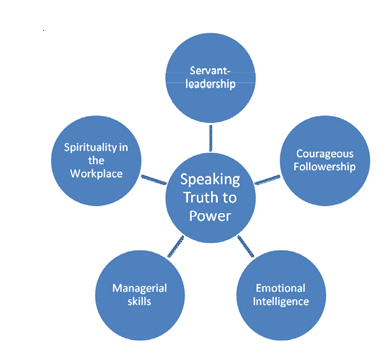

Figure 1 illustrates the five leadership constructs essential to speaking truth to power. I assert that if one construct is absent or weak, the message will lose its potency. To illustrate, if the element of being a courageous follower were removed, the messenger would be too passive to stand up to a leader. If the component of servant leadership were removed, the messenger would perhaps become too opportunistic and only pursue vain glory. If the element of spirituality were taken away, the messenger would perhaps approach power with the wrong mindset and would potentially seek to destroy the leader as opposed to help. If the aspect of emotional intelligence were weak, the messenger would not necessarily be savvy enough to formulate networks to solve problems. If the messenger lacks strong management skills, the perception of the lack of competence from the leader could compromise the essence of the truth that’s trying to be articulated.

In essence, speaking truth to power is like rolling a wheel with five spokes up a hill. Given the right push and methodology, the wheel will make it to its destination. But if one of the spokes is broken or removed, it will cause the wheel to struggle and fall before it reaches the top. I believe that numerous tragedies have occurred throughout history simply because an element (i.e., courageous followership, spirituality, servant leadership, management, or emotional intelligence) within a messenger was missing or underdeveloped. Nathan’s life teaches us that it’s possible to speak truth to power. But are we willing to pay the price to develop the five constructs enabling us to keep our leaders listening?

VI. Conclusion

The overall intent of this article was to abstract principles from the life of Nathan and struggle with the questions: Is there a systematic method to speaking truth to power and what happens to both the messenger and the message after truth has been delivered? This deliberation provided an exegesis of five biblical pericopes. First, 2 Samuel 7:1-3 focused on the probable leadership trait that empowered Nathan to become the next adviser to the king. Second, 2 Samuel 7:4-12 focused on the spirituality of the prophet and made a case that such a construct formulated his overall deliberations. Third, 2 Samuel 12:1-14 highlighted the courageous followership of Nathan and outlined how he skillfully spoke the truth to power. Fourth, 1 Kings 1:10-14 explored the emotional intelligence of the prophet as he navigated through an array of negative political realities. Fifth and finally, 2 Chronicles 9:29 explored the management capabilities of Nathan that consequently made him a credible asset within the king’s court.

About the Author

Lieutenant Commander Maurice A. Buford is a naval chaplain currently serving at the Marine Corps University at Quantico, VA. In addition to providing pastoral care to the members of this institution, he teaches ethics and leadership. He holds a Doctorate of Ministry, a Master of Divinity from the Interdenominational Theological Center, a Certificate of Advanced Graduate Studies in Human Resource Development from Regent University, and a Bachelor of Science from Tuskegee University. He is currently working on his doctorate in organizational leadership from Regent University. His areas of interest include servant leadership, emotional intelligence, community HRD, and spirituality. Note: The views of this article do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. military.

Email: MauriceBuford@aol.com

Notes

1 Brainy Quote, “Colin Powell Quotes,” http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/c/colin_powell.html (accessed April 19, 2007).

2 P. Kyle McCarter, “II Samuel: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes, and Commentary,” in The Anchor Bible (New York: Doubleday, 1984), 210-31.

3 Keith Bodner, “Nathan: Prophet, Politican and Novelist,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament (2001): 43-54.

6 Judson Cornwall and Stelman Smith, The Exhaustive Dictionary of Bible Names (Alachua, FL: Bridge- Logos, 1998).

7 R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer, and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament

(Chicago: Moody Press, 1980).

8 Robert K. Greenleaf, “Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power & Greatness,” In Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power & Greatness (New York: Paulist Press, 1977), 27.

9 Larry Spears, Servant Leadership: Quest for Caring Leadership. http://www.greenleaf.org/leadership/ read-about-it/articles/Quest-for-Caring-Leadership.html (accessed April 26, 2007).

10 Ibid.

11 Robert Baker Girdlestone, Synonyms of Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: W. M. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1897).

12 John C. Maxwell, The 21 Irrefutable Laws of Leadership (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1998), 190.

14 Gary, Yukl, Leadership in Organizations (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002). 186.

15 The Message.

16 B. Freshman, “An Exploratory Analysis of Definitions and Applications of Spirituality in the Workplace,”

Journal of Organizational Change Management 12, no. 4 (1999): 318.

18 Hanna Ashar and Maureen Lane-Maher, “Success and Spirituality in the New Business Paradigm,”

Journal of Management Inquiry 13, no. 3 (2004): 253.

19 Joan Marques, Satinder Dhiman, and Richard King, “Spirituality in the Workplace: Developing an Integral Model and Comprehensive Definition,” Journal of American Academy of Business 7, no. 1 (2005): 87.

20 Keith Bodner, “Nathan: Prophet, Politican and Novelist?” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 95 (2001): 46-47.

22 Stephen R. Covey, The Speed of Trust (New York: Free Press, 2006).

23 David B. Guralnik, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary (New York, Warner Books, 1987), 147.

24 Gary Yukl, Leadership in Organizations (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2002).

25 Ibid.

27 Guralnik, Merriam-Webster’s.

29 Yukl, Leadership in Organizations.

30 Brainy Quote, “Collin Powell Quotes.”

31 Ira, Chaleff, The Courageous Follower (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 1995).

33 Yukl, Leadership in Organizations, 147.

34 Nancy R. Scott, “How to Confront the Boss and Win,” Nancy Rathbun Scott, http://www.nancyscott.com/page50/page33/page33.html

35 Chaleff, The Courageous Follower, 26.

36 James Strong, (1996) The Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible: Showing Every Word of the Text of the Common English Version of the Canonical Books, and Every Occurrence of Each Word in Regular Order (Ontario: Woodside Bible Fellowship, 1996) S. G2384 Electronic ed.

37 Bruce Winston, “Leadership Theory: A Continuum” (PowerPoint presentation, Regent University, Virgina Beach, VA, 2006).

39 Ibid.

40 James M. Freeman, The New Manners and Customs of the Bible (Gainsville, FL: Bridge-Logos Publishers, 1984).

41 Lillian D. Bjorseth, “Dress for Success: Creating a Professional Image,” The Sideroad, http://www.sideroad.com/business_attire/dress-for-success.html

43 Winston, “Leadership Theory.”

44 Chaleff, The Courageous Follower.

46 Martin B Copenhaver, “He Spoke in Parables,” Christian Century (July 13-20, 1994): 681.

47 Ibid.

48 Chaleff, The Courageous Follower, 131.

49 Peter Salvey and John D. Mayer, “Emotional Intelligence,” Imagination, Cognition and Personality 9, no. 3 (1990): 185-211.

51 Walter A. Elwell and Philip W. Comfort, Tydale Bible Dictionary (Wheaton, Illinois:Tyndale House Publishers, 2001).

52 John C. Maxwell, Failing Forward (Nashville: Nelson Books, 2000).

53 Chaleff, The Courageous Follower, 129.

54 Craig L. Nessan, “Confidentiality: Sacred Trust and Ethical Quagmine,” Journal of Pastoral Care (1998): 352.

55 Yukl, Leadership in Organizations, 389.

56 John D. Mayer and Peter Salovey, What is Emotional Intelligence? (New York: Basic Books, 1997), 87.

57 Svetlana Holt and Steve Jones, “Emotional Intelligence and Organization Performance,” Performance Improvement 44, no. 10 (November-December 2005): 15.

58 Matthew George Easton, Easton’s Bible Dictionary (Chicago: Libronix, 1998).

59 John P. Kotter, A Force for Change: How Leadership Differs from Management (New York: Free Press, 1990).

60 Yukl, Leadership in Organizations.