Social Cognition and Corporate Entrepreneurship: A Framework for Enhancing the Role of Middle-Level Managers

- Michael G. Goldsby

Ball State University - Donald F. Kuratko

Indiana University - Jeffrey S. Hornsby

Ball State University - Jeffery D. Houghton

Abilene Christian University - Christopher P. Neck

Virginia Tech

Despite increasing research on corporate entrepreneurship, a review of the literature shows that little has been developed to improve the cognitive processes of middle managers engaged in entrepreneurial activity. One existing framework explains sustained corporate entrepreneurial activity on the basis of whether outcomes of such entrepreneurial behavior either meet or exceed the expectations set by managers before undertaking the activity. However, there is a gap in our understanding of what can be done for managers prior to that critical moment of approving or declining further entrepreneurial projects. The purpose of this paper is to address that gap in the literature by applying social cognitive theory (specifically the self-leadership concept) as a framework for middle managers to enhance their perceptions of the benefits of taking part in further corporate entrepreneurial activity.

Although there are many similarities in the general entrepreneurship process between startups, small businesses, and large corporations; there are also many significant differences, especially regarding the political factors and personal motivations inherent to larger organizations (Morris & Kuratko, 2002). Because of complex organizational policies and structures coupled with complicated information filtering between upper and lower management, the source and determinant for entrepreneurial change on a daily basis in larger organizations tends to be the middle manager.

Middle-level managers interactively synthesize information; disseminate that information to both top- and operating-level managers; and, as appropriate, champion projects that are intended to create newness (e.g., a product, service, or business unit). In other words, once a commitment is made by all managerial parties to pursue a certain set of entrepreneurial actions, middle-level managers tend to facilitate that information flows in ways that support overall project development and implementation efforts. In contrast, the role of operating-level managers is to absorb relevant external information while responding appropriately to middle-level managers' communication of information reflecting top-level managers' decisions (Floyd & Lane, 2000). As facilitators of information flows, middle-level managers play a unique role in shaping the firm's entrepreneurial actions, as determined by top-level executives and executed by first-level managers and their direct reports (Floyd & Lane; Ginsberg & Hay, 1994; Kanter, 1985; Pearce, Kramer, & Robbins, 1997). If middle managers, in particular, have a positive outlook on corporate entrepreneurship, then it is more likely that such activity will be sustained on an ongoing basis within a given company.

As Dess, Lumpkin, and McGee (1999) have observed, "Virtually all organizations-new startups, major corporations, and alliances among global partners-are striving to exploit product-market opportunities through innovative and proactive behavior"

(p. 85). In addition, Hamel (2000) noted, "We've reached the end of incrementalism, and only those companies that are capable of creating industry revolutions will prosper in the new economy"

(p. xi). And yet, it seems that large organizations in particular often struggle with implementing innovative breakthroughs because middle managers can become too focused on managing what is rather than what can be. In a section called "Why Good Management Can Lead to Failure"

from The Innovator's Dilemma, Christensen (2000) explained that well run companies can fail when decisions are made that are not aggressive enough in disruptive situations. In our experience and fieldwork, we have observed that organizations of 1,500 employees or more especially struggle with this situation. One key reason for this may be that an expanding layer of middle management may separate top decision makers from frontline operations. Middle managers who are not entrepreneurially minded will have a negative impact on innovative activities in such companies. Despite increasing research on corporate entrepreneurship, a review of the literature shows that little has been written on how to improve the thinking of middle managers engaged in creating new products, ventures, or processes. It is critical that organizations fully develop all available human capital for engaging in entrepreneurial behavior, especially the middle managers who link strategy with operations and serve in part as a filter for which products, services, and processes will be implemented.

Recently, Kuratko, Hornsby, and Goldsby (2004) presented a framework that explains sustained entrepreneurial activity in terms of individual reflections on whether the outcomes of such behavior either meet or exceed the expectations set by management before undertaking the change. Quite simply, if entrepreneurial activity is not seen as worth the effort and risk; then traditional, more conservative management will take place in the future. While this model explains the psychology and decision making that takes place at the critical moment of approving or declining future entrepreneurial projects, it offers little guidance on what could or should be done up to that point.

In this paper, we present self-leadership as a process for enhancing entrepreneurial decision making in established companies. Although Neck, Neck, Manz, and Godwin (1999) offered a framework for improving cognitive strategies relative to traditional entrepreneurial behavior in general; they did not address the role of self-leadership in promoting entrepreneurial behavior within longstanding, larger firms. Indeed, middle managers in larger firms are often overlooked completely, despite the fact that this class of management tends to be the most involved in innovative and entrepreneurial activities in established companies (Morris & Kuratko, 2002). At a time when innovation and change are seen as the key sources of competitive advantage in today's marketplace, it is imperative that managers make corporate entrepreneurship a natural way of doing business. The purpose of this paper is to address the gap in Kuratko, Hornsby, and Goldsby's (2004) work by applying self-leadership as a tool for middle managers to enhance their perceptions of the benefits of taking part in corporate entrepreneurial activity.

Corporate Entrepreneurship

As the corporate landscape becomes more complex, competitive, and global; established organizations have increasingly embraced corporate entrepreneurship for the purposes of profitability (Zahra, 1991), strategic renewal (Guth & Ginsberg, 1990), fostering innovativeness (Baden-Fuller, 1995), gaining knowledge for future revenue streams (McGrath, Venakataraman, & MacMillan, 1994), and international success (Birkinshaw, 1997). However, the concept of corporate entrepreneurship (also discussed in the literature as corporate venturing or intrapreneurship) has been evolving for at least 30 years (Hanan, 1976; Hill & Hlavacek, 1972; Peterson & Berger, 1971; Quinn, 1979). Sathe (1989), for example, defined it as a process of organizational renewal. Other researchers have conceptualized corporate entrepreneurship as embodying entrepreneurial efforts that require organizational sanctions and resource commitments for the purpose of carrying out innovative activities in the form of product, process, and organizational innovations (Alterowitz, 1988; Burgelman, 1984; Jennings & Young, 1990; Kanter, 1985; Scholhammer, 1982). This view is also consistent with Damanpour (1991) who pointed out that corporate innovation is a very broad concept encompassing "the generation, development, and implementation of new ideas or behaviors. An innovation can be a new product or service, an administrative system, or a new plan or program to organizational members"

(p. 556). In this context, corporate entrepreneurship centers on re-energizing and enhancing the ability of a firm to acquire innovative skills and capabilities. Guth and Ginsberg stressed that corporate entrepreneurship encompasses two major phenomenas: new venture creation within existing organizations and the transformation of ongoing organizations through strategic renewal. Zahra observed that

corporate entrepreneurship may be formal or informal activities aimed at creating new businesses in established companies through product and process innovations and market developments. These activities may take place at the corporate, division (business), functional, or project levels, with the unifying objective of improving a company's competitive position and financial performance. (p. 262)

After careful study of the term's conceptualizations, Sharma and Chrisman (1999) defined corporate entrepreneurship as "the process whereby an individual or a group of individuals, in association with an existing organization, create a new organization or instigate renewal or innovation within that organization"

(p. 18).

While many researchers have continued to tout the importance of corporate entrepreneurship as a growth strategy for established organizations and as an effective means for achieving competitive advantage (Kuratko, 1993; Kuratko, Ireland, & Hornsby, 2001; Lumpkin & Dess, 1996; Pinchott, 1985; Thornhill & Amit, 2001; Zahra, 1991), others have focused attention on conducting empirical studies examining the various elements of corporate entrepreneurial activities (Lumpkin & Dess; Zahra & Covin, 1995). Many within this general stream of research have emphasized the role of middle managers in developing innovative and entrepreneurial behaviors within an organization (Floyd & Woolridge, 1990, 1992, 1994; Hornsby, Kuratko, & Zahra, 2002; Kuratko, Ireland, Covin, & Hornsby, 2005). Not only can middle managers develop entrepreneurial behaviors resulting in entrepreneurial activities, they can also influence their subordinates' commitment to the activities once they are initiated. The following section more fully explains the role of middle managers in corporate entrepreneurship.

The Role of Middle Managers in Corporate Entrepreneurship

According to Floyd and Lane (2000); senior-, middle-, and first-level managers have distinct responsibilities with respect to each subprocess of corporate entrepreneurship. And, although managers at all organizational levels have critical strategic roles to fulfill for the organization to be successful (Floyd & Lane; Ireland, Hitt, & Vaidyanath, 2002), corporate entrepreneurship research has often highlighted the importance of middle-level managers' entrepreneurial actions in the firm's attempt to create new businesses or reconfigure existing ones (Floyd & Lane; Floyd & Wooldridge, 1990, 1992, 1994; Kuratko, Ireland, Covin, & Hornsby, 2005). This importance manifests itself both in terms of the need for middle-level managers to behave entrepreneurially themselves and the requirement for them to support and nurture others' attempts to do the same. Middle-level managers' work as change agents and promoters of innovation is facilitated by their organizational centrality. In a sense, they are the linchpin for the entrepreneurial strategy.

Research has suggested that middle-level managers are a hub through which most organizational knowledge flows (Floyd & Wooldridge, 1992; King, Fowler, & Zeithaml, 2001). To interact effectively with frontline managers (and their reports) and to gain access to their knowledge; middle-level managers must possess the technical competence required to understand the initial development, subsequent shaping, and continuous applications of the firm's core competencies. Simultaneously, to interact effectively with senior-level executives and to gain access to their knowledge, middle-level managers must understand the firm's strategic intent and goals as well as the political context within which these are chosen and pursued. Through interactions with senior- and first-level managers, those operating in the middle of an organization's leadership structure influence and shape their firms' corporate entrepreneurship strategies.

Entrepreneurial initiatives are inherently experiments that evolve from fundamental business concepts to more fully defined business models (Block & MacMillan, 1993), and middle-level managers have much to do with how these entrepreneurial initiatives take shape. In short, middle-level managers often serve in a refinement capacity. Their refinement behaviors characteristically involve molding the entrepreneurial opportunity into one that makes sense for the organization given the organization's strategy, resources, and political structure. First-level managers often have little sense of what the entrepreneurial opportunity must look like in order to be viable; their attention is more purely focused on the technical merit or market demand for the business concept. Top-level managers, in contrast, often have a very definite sense of the type of entrepreneurial initiatives that fit their organizations. It is characteristically the job of middle-level managers to convert malleable entrepreneurial opportunities into initiatives that fit the organization.

Sustaining Entrepreneurial Activity

As we have pointed out, the use of corporate entrepreneurship as a means for enhancing the innovative abilities of employees while increasing corporate success through the creation of new corporate ventures has expanded substantially over the past 20 years (Hornsby, Naffziger, Kuratko, & Montagno, 1993; Kuratko, Hornsby, & Goldsby, 2004; Kuratko & Montagno, 1989; Miller & Friesen, 1982; Pinchott, 1985). However, the pursuit of corporate entrepreneurial activity is difficult because it creates a newer and potentially more complex set of challenges on both a practical and theoretical level. On a practical level, organizations need guidelines to direct or redirect resources toward establishing entrepreneurial strategies. On a theoretical level, researchers need to continually reassess the components or dimensions that predict, shape, and explain the environment in which corporate entrepreneurship flourishes.

Gartner (1988) suggested that the research questions in entrepreneurial research should focus on the process of entrepreneurship rather than on the entrepreneur. The implication is that entrepreneurship is a multidimensional process with entrepreneurial traits constituting just one component of that process. Gartner called for studies that build on the previous literature and develop theories for the study of the entrepreneurship process. A direct parallel can be drawn to research concerning the corporate entrepreneurial process. Theories and models providing a framework for corporate entrepreneurship research are still fairly new. Of the currently available frameworks, interactive models of corporate entrepreneurship may prove to be the most useful for examining the role of self-leadership in the corporate entrepreneurial process. Interactive models describe the process of corporate entrepreneurship from the precursors of the decision to act entrepreneurially to actual idea implementation.

Hornsby, Naffziger, et al. (1993) have suggested an interactive model of corporate entrepreneurship which proposes a combination of circumstances that lead to internal entrepreneurial behavior by managers. Building on the work of Kuratko, Montagno, and Hornsby (1990); Hornsby, Naffziger, et al. proposed that the organizational factors of management (support, autonomy/work discretion, rewards/reinforcement, time availability, and organizational boundaries) combine with the individual characteristics of the corporate entrepreneurs (risk taking, desire for autonomy, need for achievement, goal orientation, and internal locus of control) to determine whether a precipitating or triggering event would drive entrepreneurial behavior (Schindehutte, Morris, & Kuratko, 2002). The precipitating event provides the impetus to behave entrepreneurially when the organizational and individual characteristics are conducive to such behavior.

Naffziger, Hornsby, and Kuratko (1994) applied the Porter-Lawler (1968) model of motivation directly to individual entrepreneurship in order to develop a more refined interactive model. The Naffziger et al. model suggests that the decision to become an entrepreneur is based on a combination of personal characteristics, the individual's personal environment, the individual's personal goals, and the business environment in which the individual is currently employed. According to the model, once an individual chooses to engage in entrepreneurial behavior, his or her motivation to continue is contingent upon comparisons made between actual rewards and expected rewards.

Kuratko, Hornsby, and Goldsby (2004) extended and modified these previous models to more fully explain the cycle of what sustains or causes a departure from an entrepreneurial strategy. As seen in Figure 1, they proposed that the future of an ongoing entrepreneurial strategic approach is contingent upon individual members continuing to undertake innovative activities and upon positive perceptions of the strategy by the organization's executive management, which in turn will support further allocations of necessary organizational antecedents. The first part of the model is based on theoretical foundations in previous strategy and entrepreneurship research; while the second part of the model considers the comparisons made at the individual and organizational level on organizational outcomes, both perceived and real, that influence the continuation of the entrepreneurial strategy. The second part of the model is based largely on Porter and Lawler's (1968) integrative model of motivation which incorporates important elements of Adams 's (1965) equity theory and Vroom's (1964) expectancy theory. At the present time; the Kuratko, Hornsby, and Goldsby (2004) model is the most comprehensive framework available for explaining the interactive nature of corporate entrepreneurship. Nevertheless, although an extensive focus on organizational factors is necessary for understanding how to successfully manage corporate entrepreneurship, no interactive model to date has presented guidance for middle managers on how to make decisions and handle ambiguity while engaging in entrepreneurial activity. In the following sections, we will further expand on the Kuratko, Hornsby, and Goldsby (2004) framework by suggesting how social cognitive theory in general and self-leadership in particular may be used as a tool to enhance the perceptions of middle managers in performing risky and complex entrepreneurial activities.

Social Cognitive Theory

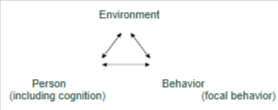

Despite growing recognition for the role of middle managers in developing entrepreneurial behaviors, more needs to be known about the specific factors that can influence middle managers to achieve this objective. Social cognitive theory is a recent theory of human behavior that may have significant potential for influencing entrepreneurial activity in today's business organizations. We believe it provides a framework that helps to facilitate entrepreneurial knowledge within established organizations. The theory recognizes the impact of the environment on human development while also placing responsibility on the individual to grow from within. It incorporates the primary critical categories of variables influencing organizational behavior; that is, cognitive, behavioral, and environmental determinants (Davis & Luthans, 1980). In short, social cognitive theory posits that the environment, the focal behavior, and the person (including internal cognitions) reciprocally interact to explain individual actions. Figure 2 (adapted from Bandura, 1977, 1986) depicts this relationship. Indeed, some theorists have argued that other explanations of human behavior are too limiting and, at best, provide only a partial explanation of the complexities of organizational behavior (Davis & Luthans, 1980).

Social cognitive theory has only recently been introduced within the entrepreneurial setting (R. K. Mitchell, Busenitz, Lant, McDougall, Morse, & Smith, 2002). A social cognitive view of corporate entrepreneurship suggests that each person can transform into an innovative and entrepreneurial individual if given the opportunity and support to develop his or her abilities. In this respect, middle managers are often constrained by lack of resources, senior management support, bureaucratic rules and regulations, and nonmotivating reward systems. As a result, middle managers may not experience or take advantage of opportunities and resources that would allow them to develop their abilities and capabilities to be entrepreneurial and innovative. Furthermore, senior management support of entrepreneurial activity is not sufficient on its own to ensure that middle managers will become more innovative and creative. While the corporate environment plays an important role in personal development, the individual is also responsible and can affect his or her own manner of entrepreneurial thinking. Thus, even though the organization can provide a supportive environment for entrepreneurial activity, the middle manager must also actively manage himself or herself in understanding and taking advantage of these opportunities.

Unlike some traditional views of human behavior, social cognitive theory suggests a mediating role for the effects of cognitive processes between the individual and the environment (Neck & Manz, 1992). Because social cognitive theory recognizes this mediating role, it offers entrepreneurship scholars a way of aiding middle managers in the development of innovation and creativity in their everyday work lives. Much of the entrepreneurship literature has focused on changing environmental factors, but little of it has focused on making changes in entrepreneurial thinking. Even though the entrepreneurial mindset has been recognized, the process for bringing it about has not been fully developed in the literature. Social cognitive theory offers a useful framework for understanding the entrepreneurial process and provides tools for improving cognitions that affect entrepreneurial thinking and behavior in firms (Chen, Greene, & Crick, 1998).

Successful managing requires preparation and persistence. Entrepreneurial behavior at the middle manager level can be confounded by a lack of confidence to successfully address new market opportunities. People are affected by their surroundings, but they still make behavioral choices that help to shape their lives. Middle managers have the potential to transform themselves into corporate entrepreneurs, influenced but not dominated by their environments. The process of self-leadership, operating within the framework of social cognitive theory, offers specific strategies for assisting these managers in achieving this objective and fulfilling the entrepreneurial goals of the company.

Self-Leadership Applied to Corporate Entrepreneurial Activity

Self-leadership is a process of self-influence that allows people to achieve a level of self-direction and self-motivation needed for optimal performance (Houghton, Neck, & Manz, 2003; Manz & Neck, 1991; Neck & Houghton, 2006; Neck & Manz, 1992, 1996a, 1996b, 2007; Neck, Manz, & Stewart, 1995; Neck & Milliman, 1994). Self-leadership is a normative model of behavior and cognition that operates within a social cognitive theoretical context and prescribes specific behavioral and cognitive strategies designed to increase individual effectiveness (Neck & Houghton; Neck & Manz, 2007). Self-leadership's cognitive strategies place particular importance on a person's ability to establish and maintain constructive thought patterns. Just as we develop both functional and dysfunctional behavioral habits, we also develop functional and dysfunctional patterns of thinking. These mindsets influence our perceptions, the way we process information, and the choices we make in an almost automatic way (Neck & Barnard, 1996).

Two common and contrasting patterns of thinking are opportunity thinking and obstacle thinking (Neck & Manz, 2007). A manager who engages in opportunity thinking focuses on constructive ways of dealing with challenging situations. By contrast, a person who engages in obstacle thinking focuses on the negative aspects of challenging situations, reasons to give up and retreat from problems or challenges. Research has shown that the opportunity thinker will exert more effort and persist during the course of their work (Neck & Manz, 1992, 1996a; Seligman, 1991, 1994). These thought patterns may correlate strongly with how people behave in entrepreneurial and innovative activities. Even the most entrepreneurial of managers can lose the entrepreneurial edge due to day-to-day pressures, the administrative demands of organizational policies, and the need for more systematic approaches as an innovative concept grows into a large internal enterprise.

Opportunity thinkers tend to fare better in the face of challenging situations because they are more likely to believe in change as a necessary and beneficial goal and will work hard to recognize and develop the capabilities necessary to achieve such changes. In contrast, obstacle thinkers do not want to deal with the hassle of addressing the difficult issues surrounding change. In entrepreneurial terms, this type of person is the classic bureaucrat who believes in the status quo while blocking all initiatives for change. An obstacle thinker would be less likely to examine all possible options available in a time of change, crisis, or opportunity. Managers who understand the power of opportunity thinking and the strategies that help to develop this type of thinking give themselves an important performance edge.

As discussed above, two factors of social cognitive theory-environment (organizational antecedents) and focal behavior (entrepreneurial activity and outcomes)-have been included in earlier interactive models of corporate entrepreneurship. However, these previous interactive models have not examined in depth the third factor of social cognitive theory: the cognition of middle managers in entrepreneurial endeavors. We suggest that managers can learn to engage in opportunity thinking and thus exhibit less dysfunctional, status quo thinking and more entrepreneurial thinking by learning to analyze and manage the three primary cognitive elements of self-leadership: internal dialogue (self-talk), visualization (mental imagery), and beliefs and assumptions.

Research has shown that by controlling these three factors, one can carry out a variety of tasks and activities more successfully. For example, a study of aspiring school counselors demonstrated that the use of mental imagery improved decision making, strategy formulation, and other complex skills (Baker, Johnson, Kopola, & Strout, 1985). In sports psychology, many studies have confirmed the efficacy of purposely managing one's own thinking, especially by using mental imagery. A meta-analysis of 60 different studies revealed that when athletes mentally practice a task; their performance of that task consistently improves, particularly for tasks that are most influenced by athletes' psychological outlook (Feltz & Landers, 1983). Finally, one study suggested that employees who participated in a self-leadership training intervention experienced enhanced mental performance, affective states, job satisfaction, and self-efficacy expectations over those not receiving the training (Neck & Manz, 1996a). We now examine these concepts in greater depth with special attention to their corporate entrepreneurship applications.

Self-talk is what we covertly tell ourselves. Butler (1981) suggested that we engage in "an ever constant dialogue"

(p. 1) with ourselves in order to influence our behavior, feelings, self-esteem, and stress level. Individuals can improve their personal effectiveness by analyzing and reshaping their self-dialogues in more positive and constructive ways. For example, self-talk was one treatment component that helped smokers smoke fewer cigarettes each day (Steffy, Meichenbaum, & Best, 1970). Furthermore, in a study of handicapped children, self-talk training improved the children's performance and communication skills (Swanson & Kozleski, 1985). Likewise, positive self-talk may also offer the corporate entrepreneur a tool for enhancing performance. Managers who bring their own verbalization of the myths and misconceptions of innovation and change to a level of awareness before rethinking and positively reverbalizing may be able to improve their entrepreneurial behavior. Those managers who maintain negative perspectives on corporate entrepreneurship likely verbalize new products, services, and processes in negative tones. Jackman and Strober (2003) explained how reframing negative emotions and self-statements into more positive, productive thoughts can improve performance. Jackman and Strobe's framework is modified and applied to corporate entrepreneurship in Table 1.

An apprehensive corporate entrepreneur engaged in a new project may find addressing negative thoughts and self-dialogues in the fashion demonstrated in Table 1 to be quite useful. For instance, managers could challenge the belief that a situation is too complex and risky by reversing their thoughts and telling themselves something like,

Everyone struggles with change and the unknown, but it's only through taking chances that we give ourselves the opportunity to succeed. After all, rewards are based on the risks we take. Instead of worrying about failure, I'm going to pursue this project with all the creative ability I have and work with others to create new value for our customers and company.

After attempting this type of positive self-talk a number of times, corporate entrepreneurs would likely be able to internalize it, so that they could use it effectively in similar situations in the future.

| Negative Emotion | Maladaptive Response | Reframing Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Anger ("I'm mad at my boss because he won't talk to me directly.") | Acting out (stomping around, complaining, being irritable) | "It's up to me to get the feedback I need." |

| Anxiety ("I don't know what will happen.") | Brooding (withdrawal) | "Finding out can open up new opportunities for me." |

| Fear of failure ("I don't want to do this.") | Denial, procrastination, self-sabotage (canceling meetings) | "Taking the initiative puts me in charge and gives me the chance to shine." |

| Fear of reprisal ("If I mess up, will I get a pink slip?") | Denial ("I'm doing okay now and don't need to take a chance.") | "I wonder what skills and lessons I can learn from this opportunity?" |

| Fear of change ("How will I ever learn to do all this?") | Denial (keep doing things the same way as before) | "I must change to keep myself marketable. Everyone must always be improving in today's world or else." |

| Ambivalence ("Should I get involved or not?") | Procrastination, passivity (waiting for someone else to take the initiative and solve problems and pursue opportunities) | "What really serves my interests best? Nobody is as interested in these topics as I am. I need to take action now." |

| Resignation ("I have to avoid these projects if at all possible.") | Resistance to change ("It's hard to do my job as it is now.") | "I'll be much happier working on new and interesting projects instead of the same old thing. That's why I do what I do." |

Note. Adapted and modified from Jackman and Strober (2003) for entrepreneurial self-talk.

Visualization , or mental imagery, refers to imagining successful performance of a task before it is actually completed. Research in management, sports psychology, counseling education, clinical psychology, and other fields has suggested that visualization can serve as a very effective performance enhancement technique (Neck & Manz, 1992). In terms of corporate entrepreneurship, positive visualizations may lead to more new products, services, and processes for the company and to greater innovation, risk taking, and proactive behaviors among the managers. For example, managers considering pursuing a new idea could use positive mental imagery (or visualization) when making this decision. Corporate entrepreneurs would picture themselves bringing the idea to market and the positive response it would receive. They would also imagine being recognized by their company for taking a risk and seeing it through. They might further envision the workplace becoming more open to creative pursuits with everyone enjoying coming to work. They could picture everyone working together and putting forth full efforts to make the company a world-class operation.

On the other hand, corporate entrepreneurs could use the same technique negatively, picturing themselves as failures in the new endeavor. The resulting lack of confidence could well lead to the very failure they have imagined. Existing entrepreneurship research has provided a further window into how a corporate entrepreneur could better visualize positive outcomes to overcome this danger. In examining the motivational aspects of the entrepreneurial process, the literature has suggested that certain goal orientations are commonly ascribed to entrepreneurs. For example, Stewart, Watson, Carland, and Carland (1998) found that entrepreneurs enjoy the opportunity to seek financial and personal rewards. Likewise, Kuratko and Hodgetts (2004) pointed out 17 psychological characteristics most commonly associated with entrepreneurship including commitment, perseverance, achievement, drive, and opportunity orientation. In addition, Greenberger and Sexton (1988) identified the entrepreneur's vision as a significant guiding force in the development of new ideas.

Managerial problems often stem from dysfunctional thinking that can hinder personal effectiveness and lead to various forms of stress and depression. However, successful corporate entrepreneurs tend to maintain consistent, positive beliefs and assumptions that can be summarized as an entrepreneurial mindset (McGrath & MacMillan, 2000). The first component of the entrepreneurial mindset involves framing the challenge. In other words, there needs to be a clear definition of the specific challenges that everyone involved with an innovative project must understand. It is important to think about and reiterate the challenge regularly. Corporate entrepreneurs also have the responsibility of absorbing the uncertainty that is perceived by other organizational members. Opportunity thinkers make uncertainty less daunting by creating the self-confidence that lets others act on opportunities without seeking managerial permission. Fellow managers and employees must not be overwhelmed by the complexity inherent in many innovative situations. The corporate entrepreneur must also define gravity; that is, what must be accepted and what cannot be accepted. The term gravity is used to represent the concept of limiting conditions. For example, there is gravity on earth, but that does not necessarily mean that it must limit our lives. If freed from the psychological cage of believing that gravity makes flying impossible, creativity can permit us to invent an airplane or spaceship. This is what the entrepreneurial mindset and opportunity thinking are all about, seeing opportunities where others see barriers and limits. Opportunity thinkers also are not daunted by the political nature of organizations but instead realize that politics are just a part of the process of getting things done. Corporate entrepreneurs use creative tactics; political skills; and the ability to regroup, reorganize, and attack from another angle when necessary. They believe that solutions can be delivered in any situation, which is especially appropriate in corporate entrepreneurship given the presence of triggering events all companies face in today's marketplace. A final step for attaining an entrepreneurial mindset is for managers to keep their finger on the pulse of the project. This involves constructive monitoring and control of the developing opportunity, along with providing encouragement to fellow managers and employees involved in the project.

In the contemporary organization, all managers must be entrepreneurs. The process described can assist managers in attaining the beliefs and assumptions required to develop an entrepreneurial mindset. This process becomes a core part of helping managers to define their jobs around opportunity seeking instead of opportunity avoidance. Doing so will help managers to develop into innovation champions and change agents rather than corporate bureaucrats.

One final application of the visualization strategy relates to the process of visualizing outcomes and rewards. The corporate entrepreneurship literature has discussed a number of important motivational factors; and one key element that consistently emerges is the concept of rewards, both extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic rewards generally come in the form of monetary compensation or gaining equity in the firm (Kuratko, Hornsby, & Naffziger, 1997; Shaver & Scott, 1991). Intrinsic rewards, in contrast, accrue to someone through task accomplishment, specifically in the satisfaction of the need for control and the need for achievement (Bird, 1988; Johnson, 1990). Extrinsic rewards include acquiring personal wealth and securing the future for one's family; while intrinsic rewards include controlling one's destiny, public recognition, excitement, personal growth, and self-efficacy. Kuratko, Hornsby, and Naffziger organized entrepreneurial rewards into 16 distinct items. Knowledge of these items could assist corporate entrepreneurs in developing a vision of what they hope to attain by taking on new projects. The vision will vary from person to person, but the rewards in general can easily be imagined and pursued by many within the organization. If managers were to imagine attaining these rewards, they would most likely develop an image of the person they hope to become if they are successful in pursuing entrepreneurial projects in the company. In this manner, corporate entrepreneurs could visualize themselves to be like their business heroes and mentors.

In short, we propose that the cognitive self-leadership strategies discussed will affect a middle managers' entrepreneurial behaviors by creating an opportunistic thinking pattern, which will in turn increase self-efficacy for engaging in such behaviors (Neck, Neck, et al., 1999). Self-efficacy, a primary construct within social cognitive theory, describes a person's self-assessment of the capabilities necessary to perform a specific task (Bandura, 1977, 1986). A major objective of the self-leadership strategies described is the enhancement of self-efficacy perceptions leading to higher performance levels (Neck & Houghton, 2006; Neck & Manz, 2007). Research has suggested that high levels of task specific self-efficacy lead to higher performance standards, greater effort, greater persistence, and greater overall task effectiveness (Harrison, Rainer, Hochwarter, & Thompson, 1997). Empirical evidence has provided some support for the effectiveness of self-leadership strategies in increasing self-efficacy perceptions. For instance, Neck and Manz (1996a) demonstrated significant difference in self-efficacy between a self-leadership training group and a nontraining control group in a training effects field study. Similarly, Prussia , Anderson , and Manz (1998) examined self-efficacy as a mediator of the relationship between self-leadership strategies and performance outcomes and found significant relationships between self-leadership strategies, self-efficacy perceptions, and task performance. Finally, McCormick and Martinko (2004) suggested that an optimistic attributional style, a concept very similar to opportunity thinking, will lead to higher levels of self-efficacy in leaders. Findings such as these suggest that thinking processes and self-efficacy may serve as primary mechanisms through which cognitive self-leadership strategies affect entrepreneurial behaviors and performance outcomes.

Conclusion

We close by providing specific details on how corporate entrepreneurs could use cognitive self-leadership strategies to enhance their entrepreneurial performance (Manz & Neck, 1991; Neck & Barnard, 1996; Neck & Manz, 1996a). It embodies all the models discussed in the paper and consists of only five steps:

- Observe and record existing beliefs and assumptions, self-talk, and mental imagery patterns regarding change, innovation, and entrepreneurship in the company and within oneself.

- Analyze how entrepreneurial and creative these thoughts are.

- Identify and develop more entrepreneurial and creative thoughts to substitute for any negative ones, perhaps writing these down. The manager can now actively apply entrepreneurial thinking and language.

- Try substituting more creative and entrepreneurial thinking when faced with an opportunity, crisis, or challenge.

- Continue monitoring beliefs, self-talk, and mental images; while maintaining the new, more entrepreneurial ones.

Research has suggested that effective use of the self-leadership strategies discussed here can give managers the extra tools necessary for optimal performance (Neck & Houghton, 2006). We have argued that these tools will work especially well when used by middle-level managers to improve their thinking patterns and self-efficacy for engaging in corporate entrepreneurship behaviors, thus leading to greater and more effective corporate entrepreneurial activity. We further suggest that as middle-level managers model the usage of these cognitive self-leadership strategies and the resulting corporate entrepreneurship behaviors; they may facilitate the adoption of these strategies and behaviors by others in the organization, especially first-level managers (Manz & Sims, 2001).

It is important to note, however, that the effectiveness of these self-leadership strategies can be limited by certain environmental contingencies. For example, research has suggested that factors relating to job role can affect the leadership behaviors of managers (Herold & Fields, 2004). Indeed, middle managers may find that certain job role effects serve as barriers to the cognitive adjustments necessary to support entrepreneurial activities. Likewise, if not structured properly, an organization's reward system may actually serve to discourage middle managers from engaging in entrepreneurial activities. An organization may communicate a message that encourages risk taking and innovation yet fail to reward managers for such behaviors or, worse yet, impose penalties for the lack of short-term performance. Limiting factors such as these may work to curtail corporate entrepreneurship behaviors among middle managers regardless of their use of the strategies discussed here. Nevertheless, although people are clearly affected by these types of limiting factors, they can still make important choices regarding their work behavior. Social cognitive theory suggests that people need not accept the status quo as a rationalization for corporate bureaucracies and outdated strategies.

Entrepreneurship researchers are beginning to look more deeply into individual factors of performance and opportunity recognition. J. R. Mitchell, Friga, and Mitchell's (2005) work on intuition and Kuratko , Ireland , Covin, and Hornsby's (2005) examination of entrepreneurial behavior highlight some of the most recent work in this area. Future research should test whether corporate entrepreneurs with better social cognitive and self-leadership skills outperform managers who have more of an obstacle mindset. If so, then training could be developed to utilize self-leadership as a process to enhance entrepreneurship and innovation in the organization. The general effectiveness of cognitive self-leadership strategies has been demonstrated in an earlier training-intervention type field study that showed increased mental performance, positive affect (enthusiasm), job satisfaction, and decreased negative affect (nervousness) for those receiving training in the cognitive self-leadership strategies relative to those who did not (Neck & Manz, 1996a). It is the task of future researchers and practitioners to explore whether or not this type of training intervention could be successful in facilitating corporate entrepreneurship behaviors in middle managers.

To summarize, social cognitive theory states that people are capable of shaping their own behavior and thus are responsible for their actions. Each manager has the potential to transform into a corporate entrepreneur who is influenced but not controlled by organizational antecedents and strategies. We agree that these organizational factors can have an impact on managers, but successful entrepreneurial outcomes are also based on the thinking and behavior of the managers themselves. This paper has offered social cognitive theory and self-leadership as frameworks for addressing the gaps in the previous models of interactive corporate entrepreneurship. At a time when companies are under pressure to adapt and lead in ever-changing markets, maximum entrepreneurial efforts and focus by managers at all levels of the company are required to remain in business.

About the Authors

Dr. Michael G. Goldsby is the Stoops Distinguished Professor of Entrepreneurship at Ball State University. His research interests include the study of ethical perspectives, applied creativity, and personal development of entrepreneurs. Some of his research has appeared in the Journal of Small Business Management, Journal of Business Ethics, International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Journal of Applied Management and Entrepreneurship, Group and Organization Management, and Journal of Managerial Psychology. He also received the Jack Hoover Award for Teaching Excellence while at Virginia Tech earning his doctorate in management. Email: mgoldsby@bsu.edu

Dr. Donald F. Kuratko is the Jack M. Gill Chair of Entrepreneurship; Professor of Entrepreneurship & Executive Director of the Johnson Center for Entrepreneurship & Innovation for the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University - Bloomington. His research has concentrated in the areas of entrepreneurship, corporate entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial growth issues. Dr. Kuratko has authored 22 books including one of the nation's leading texts, Entrepreneurship: Theory, Process, Practice (7th ed.; South-Western/Thomson, 2007). Email: dkuratko@indiana.edu

Dr. Jeffrey S. Hornsby holds the George and Frances Ball Distinguished Chair in Management and Entrepreneurship at Ball State University. He has published nearly 50 refereed journal articles in such outlets as Journal of Applied Psychology, Strategic Management Journal, Academy of Management Executive, Journal of Business Venturing, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, and Journal of Small Business Management. He has also cowritten three books on human resource management and new venture management. E-mail: jhornsby@bsu.edu

Dr. Jeffery D. Houghton is an Associate Professor of Management at Abilene Christian University (Abilene, TX ), where he is currently serving as Researcher-in-Residence in the Adams Center for Teaching Excellence. His research specialties include human behavior, motivation, personality, and leadership. Dr. Houghton has also served as Faculty-in-Residence for the ACU in Oxford (England) and the ACU in Latin America (Montevideo, Uruguay) programs. Email: jeff.houghton@coba.acu.edu

Dr. Christopher P. Neck is an Associate Professor of Management at Virginia Tech. His research interests include self-leadership, employee fitness, and group processes. He has published over 80 articles in such journals as Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Making Processes, Academy of Management Executive, and Human Relations. He has authored eight books including his most recent, Mastering Self-Leadership: Empowering Yourself for Personal Excellence (4th ed.). E-mail: christopherneck@yahoo.com

References

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In Leonard Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 267-299). New York : Academic Press.

Alterowitz, R. (1988). New corporate ventures. New York : Wiley.

Baden-Fuller, C. (1995). Strategic innovation, corporate entrepreneurship and matching outside-in to inside-out approaches to strategy research. British Journal of Management, 6, S3-S16.

Baker, S. B. E., Johnson, E., Kopola, M., & Strout, N. J. (1985). Test interpretation competence: A comparison of microskills and mental practice training. Counselor Education and Supervision, 25, 31-43.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Towards a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bird, B. J. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13 (3), 442-453.

Birkinshaw, J. (1997). Entrepreneurship in multinational corporations: The characteristics of subsidiary initiatives. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 207-229.

Block, Z., & MacMillan, I. (1993). Corporate venturing. Boston, MA : Harvard Business School Press.

Burgelman, R. A. (1984). Designs for corporate entrepreneurship. California Management Review, 26, 154-166.

Butler , P. (1981). Talking to yourself. San Francisco: Harper and Row.

Chen, C. C., Greene, P., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13, 295-316.

Christensen, C. (2000). The innovator's dilemma. New York: HarperBusiness.

Damanpour, F. (1991). Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of effects of determinant and moderators. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 355-390.

Davis, T. R. V., & Luthans, F. (1980). A social learning approach to organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 5, 281-290.

Dess, G. G., Lumpkin, G. T., & McGee, J. E. (1999). Linking corporate entrepreneurship to strategy, structure, and process: Suggested research directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(3), 85-102.

Feltz, D. L., & Landers, D. M. (1983). The effects of mental practice on motor skill learning and performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Sport Psychology, 5(1), 25-57.

Floyd, S. W., & Lane, P. J. (2000). Strategizing throughout the organization: Managing role conflict in strategic renewal. Academy of Management Review, 25, 154-177.

Floyd, S. W., & Woolridge, B. (1990). The strategy process, middle management involvement, and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 231-242.

Floyd, S. W., & Woolridge, B. (1992). Middle management involvement in strategy and its association with strategic type: A research note. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 53-168.

Floyd, S. W., & Woolridge, B. (1994). Dinosaurs or dynamos? Recognizing middle management's strategic role. Academy of Management Executive, 8, 47-58.

Gartner, W. B. (1988). Who is the entrepreneur? Is the wrong question. American Journal of Small Business, 12(4), 11-32.

Ginsberg, A., & Hay, M. (1994). Confronting the challenges of corporate entrepreneurship: Guidelines for venture managers. European Management Journal, 15, 91-112.

Greenberger, D. B., & Sexton, D. L. (1988). An interactive model of new venture creation. Journal of Small Business Management, 26, 107.

Guth, W. D., & Ginsberg A. (1990). Corporate entrepreneurship. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 5-15.

Hamel, G. (2000). Leading the revolution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Hanan, M. (1976). Venturing corporations-Think small to stay strong. Harvard Business Review, 54(3), 139-148.

Harrison, A. W., Rainer, R. K., Jr., Hochwarter, W. A., & Thompson, K. R. (1997). Testing the self-efficacy-performance linkage of social-cognitive theory. The Journal of Social Psychology, 137, 79-87.

Herold, D. M., & Fields, D. L. (2004). Making sense of subordinate feedback for leadership development: Confounding effects of job role and organizational rewards. Group and Organizational Management, 29, 686-703.

Hill, R. M., & Hlavacek, J. D. (1972). The venture team: A new concept in marketing organizations. Journal of Marketing, 36, 44-50.

Hornsby, J. S., Kuratko, D. F., & Zahra, S. A. (2002). Middle managers' perception of the internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship: Assessing a measurement scale. Journal of Business Venturing, 17, 49-63.

Hornsby, J. S., Naffziger, D. W., Kuratko, D. F., & Montagno, R. V. (1993). An interactive model of the corporate entrepreneurship process. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17(2), 29-37.

Houghton, J. D., Neck, C. P., & Manz, C. C. (2003). Self-leadership and superleadership: The heart and art of creating shared leadership in teams. In C. L. Pearce & J. A. Conger (Eds.), Shared leadership: Reframing the how's and why's of leadership (pp. 123-140). Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage.

Ireland , R. D., Hitt, M. A., & Vaidyanath, D. (2002). Strategic alliances as a pathway to competitive success. Journal of Management, 28, 413-446.

Jackman, J. M., & Strober, M. H. (2003). Fear of feedback. Harvard Business Review, 81(4), 101-108.

Jennings , D. F., & Young, D. M. (1990). An empirical comparison between objective and subjective measures of the product innovation domain of corporate entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 15, 53-66.

Johnson, B. R. (1990). Toward a multidimensional model of entrepreneurship: The case of achievement motivation and the entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 14(3), 39-54.

Kanter, R. M. (1985). Supporting innovation and venture development in established companies. Journal of Business Venturing, 1, 47-60.

King, A. W., Fowler, S. W., & Zeithaml, C. P. (2001). Managing organizational competencies for competitive advantage: The middle-management edge. Academy of Management Executive, 15(2), 95-106.

Kuratko, D. F. (1993). Intrapreneurship: Developing innovation in the corporation. Advances in global high technology management. High Technology Venturing, 3, 3-14.

Kuratko, D. F., & Hodgetts, R. M. (2004). Entrepreneurship: Theory, process & practice (6th ed.). Mason , OH: SouthWestern.

Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Goldsby, M. G. (2004). Sustaining corporate entrepreneurship. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 5(2), 77-89.

Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Naffziger, D. W. (1997). An examination of owner's goals in sustaining entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 35(1), 24-34.

Kuratko, D. F., Ireland , R. D., Covin, J. G., & Hornsby, J. S. (2005). A model of middle-level managers' entrepreneurial behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(6), 699-716.

Kuratko, D. F., Ireland , R. D., & Hornsby, J. S. (2001). The power of entrepreneurial outcomes: Insights from Acordia, Inc. Academy of Management Executive, 15(4), 60-71.

Kuratko, D. F., & Montagno, R. V. (1989). The intrapreneurial spirit. Training and Development Journal, 43(10), 83-87.

Kuratko, D. F., Montagno, R. V., & Hornsby, J. S. (1990). Developing an entrepreneurial assessment instrument for an effective corporate entrepreneurial environment. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 49-58.

Lumpkin, G. T., & Dess, G. C. (1996). Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review, 21, 135-172.

Manz, C. C., & Neck, C. P. (1991). Inner leadership: Creating positive thought patterns. The Academy of Management Executive, 5(3), 87-95.

Manz, C. C., & Sims, H. P., Jr. (2001). The new superleadership: Leading others to lead themselves. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

McCormick, M. J., & Martinko, M. J. (2004). Identifying leader social cognitions: Integrating the causal reasoning perspective into social cognitive theory. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 10(4), 2-11.

McGrath, R. G., & MacMillan, I. C. (2000). The entrepreneurial mindset. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

McGrath, R. G., Venkataraman, S., & MacMillan, I. C. (1994). The advantage chain: Antecedents to rents from internal corporate ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 351-369.

Miller, D., & Friesen, P. H. (1982). Innovation in conservative and entrepreneurial firms: Two models of strategic momentum. Strategic Management Journal, 3(1), 1-25.

Mitchell, R. K., Busenitz, T., McDougall, P. P., Morse, E. A., & Smith, J. S. (2002). Toward a theory of entrepreneurial cognition: Rethinking the people side of entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(2), 93-104.

Mitchell, J. R., Friga, P. N., & Mitchell, R. K. (2005). Untangling the intuition mess: Intuition as construct in entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(6), 653-680.

Morris, M. H., & Kuratko, D. F. (2002). Corporate entrepreneurship. Mason , OH: SouthWestern.

Naffziger, D., Hornsby, J. S., & Kuratko, D. F. (1994). A proposed research model of entrepreneurial motivation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3), 29-39.

Neck, C. P., & Barnard, A. H. (1996). Managing your mind: What are you telling yourself? Educational Leadership, 53(6), 24-7.

Neck, C. P., & Houghton, J. D. (2006). Two decades of self-leadership theory and research: Past developments, present trends, and future possibilities. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(4), 270-295.

Neck, C. P., & Manz, C. C. (1992). Thought self-leadership: The influence of self-talk and mental imagery on performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(7), 681-699.

Neck, C. P., & Manz, C. C. (1996a). Thought self-leadership: The impact of mental strategies training on employee cognition, behavior, and affect. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17, 445-467.

Neck, C. P., & Manz, C. C. (1996b). Total leadership quality: Integrating employee self-leadership and total quality management. In D. Fedora & S. Ghosh (Eds.), Advances in the management of organizational quality (Vol. 1, pp. 39-77). Greenwich , CT: JAI Press.

Neck, C. P., & Manz, C. C. (2007). Mastering self-leadership: Empowering yourself for personal excellence (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River , NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Neck, C. P., & Milliman, J. (1994). Thought self-leadership: Finding spiritual fulfillment in organizational life. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 9(6), 9-16.

Neck, C. P., Neck, H. M., Manz, C. C., & Godwin, J. (1999). I think I can; I think I can: A self-leadership perspective toward enhancing entrepreneur thought patterns, self-efficacy, and performance. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 14(6), 477-501.

Neck, C. P., Stewart, G., & Manz, C. C. (1995). Thought self-leadership as a framework for enhancing the performance of performance appraisers. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 31, 278-302.

Pearce, J. A., Kramer, T. R., & Robbins, D. K. (1997). Effects of managers' entrepreneurial behavior on subordinates. Journal of Business Venturing, 12, 147-160.

Peterson, R., & Berger, D. (1971). Entrepreneurship in organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16(1), 97-106.

Pinchott, G. (1985). Intrapreneurship. New York: Harper & Row.

Porter, L. W., & Lawler, E. L., III. (1968). Managerial attitudes and performance. Homewood , IL: Richard D. Irwin, Inc.

Prussia , G. E., Anderson , J. S., & Manz, C. C. (1998). Self-leadership and performance outcomes: The mediating influence of self-efficacy. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 523-538.

Quinn, J. (1979). Technological innovation, entrepreneurship, and strategy. Sloan Management Review, 20(3), 19-30.

Sathe, V. (1989). Fostering entrepreneurship in large diversified firm. Organizational Dynamics, 18, 20-32.

Schindehutte, M., Morris, M. H., & Kuratko, D. F. (2000). Triggering events, corporate entrepreneurship and the marketing function. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 8(2), 18-30.

Schollhammer, H. (1982). Internal corporate entrepreneurship. In C. Kent, D. Sexton, & K. Vesper (Eds.), Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship (pp. 352-373). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Seligman, M. (1991). Learned optimism. New York: Knopf.

Seligman, M. (1994). What you can change and what you can't. New York: Knopf.

Sharma, P., & Chrisman, J. J. (1999). Toward a reconciliation of the definitional issues in the field of corporate entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(3), 11-28.

Shaver, K. G., & Scott, L. R. (1991). Person, process, choice: The psychology of new venture creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(2) 23-46.

Steffy, R. A., Meichenbaum, D., & Best, J. A. (1970). Aversive and cognitive factors in the modification of smoking behavior. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 8, 115-125.

Stewart, W. H., Watson, W. E., Carland, J. C., & Carland, J. W. (1998). A proclivity for entrepreneurship: A comparison of entrepreneurs, small business owners, and corporate managers. Journal of Business Venturing, 14, 189-214.

Swanson, H. L., & Kozleski, E. B. (1985). Self-talk and handicapped children's academic needs: Applications of cognitive behavior modification. Techniques: A Journal for Remedial Education and Counseling, 1, 115-127, 367-379.

Thornhill, S., & Amit, R. (2001). A dynamic perspective of internal fit in corporate venturing. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 25-50.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York : John Wiley.

Zahra, S. A. (1991). Predictors and financial outcomes of corporate entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Venturing, 6, 259-286.

Zahra, S. A., & Covin, J. G. (1995). Contextual influences on the corporate entrepreneurship-performance relationship: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 10, 43-58.