The Jerusalem Council: A Pivotal and Instructive Paradigm

In this article, I argue for the centrality of the Jerusalem Council in the Book of Acts and the ways in which Luke provides direction for his community in resolving conflict in such a way that leads to the advance of the gospel (Acts 15:1-16:5). This is a critical moment in terms of the relationship between Jewish Christians and Gentile Christians. This narrative of conflict-resolution–advance serves as a case study for Luke’s readership in terms of various processes that help the community find the will of God in changing circumstances. Dynamics include the divine initiative, the inclusionary and saving activity of God, commitment to unity, shared stories of experience and precedent, the Holy Spirit, Scripture, decisions, compromise, and clear communication. He helps the early communities to relive the event and its nuances, to embrace and to adopt his point of view in the process of conflict resolution in an ever-changing landscape. Such elements in the conflict resolution process possess implications for leadership and groups in understanding and application of the text to twenty-first century contexts.

How ought the Church understand its identity and how should the Church practice its identity when confronting conflicts? Luke provides a pivotal and instructive example in his story of the Jerusalem Council. The aim of this paper is to establish that Luke uses Acts 15:1-16:5 not only to legitimize the Gentile mission, but in being one of a series of case studies that demonstrates a process of conflict–resolution–advance of the Christian message, it reveals how the Church can resolve its conflicts, which will lead to an advance in terms of internal strength and numerical growth. This is especially true as the Christian message progresses into new geographical areas with new ethnic groups with pressing issues and conflicts. The story of the Council is the lengthiest of several case studies involving conflict resolution. In this essay, I propose:

1. The pivotal role of the Jerusalem Council in the book of Acts

2. The various elements of conflict (threats)

3. The numerous dynamics that are part of the resolution

4. The ways in which the process advances the Christian message

The entire process of conflict–resolution–advance reflects a careful interplay of narrative, stories within the narrative, theology, and implied praxis for Luke’s readership. Luke wishes that his readers both understand and embrace the process and its implications; the narrative offers a “lived theology” for Luke that continues the story of what Jesus began to do and teach (Acts 1:1) through the witness of the Church. As such, the story becomes prescriptive for the early Church to follow as they encounter conflicts.

Other critical approaches have been taken to the Acts 15 narrative: textcriticism,1 source criticism,2 historical-criticism3 and the relationship of Acts 15 to Galatians 2,4 redaction criticism,5 and rhetorical/linguistic criticism.6 Often such approaches atomize and control the text with a specific agenda in mind. Such disciplines frequently deal with the archaeology of the text,7 but do not offer a holistic approach to the text as it now stands.

I. The Pivotal Role of the Jerusalem Council in the Book of Acts

The narrative of the Jerusalem Council is pivotal in the Book of Acts, for it functions both to divide Acts into two panels (first panel = Acts 1:1-14:28; second panel = 16:6-31) as well as to serve as a hinge, joining both panels. Luke’s story of the Council contains many elements: geography, biography, history, case studies, and theology that are inherent in the first panel, addressed in the Council, which then extend in the second panel of Acts.

Geography

In Acts 15, Luke focuses upon Antioch and Jerusalem. The problem raised in Antioch (15:1-2) is discussed, resolved, and formalized in Jerusalem (15:2b-29); from Jerusalem, the emissaries of the letter return to Antioch to communicate the Jerusalem resolve in letter and person (15:30-35). Finally, some of the emissaries return in peace to Jerusalem (15:34). Had the issue not been resolved in Jerusalem, the danger and consequence of a divided Church (one in Jerusalem and another in Antioch) would have posed a real threat to the unity of the early Church. Implicitly, Jerusalem possesses the authority to resolve the question; for the Jews, Jerusalem was regarded as the center of the world.8 Luke locates the previous ministry of Barnabas and Saul in Antioch for a full year (11:25-26) and calls the readers’ attention to the fact that the disciples were first called Christians in Antioch (11:26). Further, Luke also notes that at Antioch, the prophets and teachers were Spirit-directed to set Barnabas and Saul apart for a divinely-called work (13:1-3). It is vital for Luke that there is harmony between the two places.

The two cities belong to the broader geographical progression from Jerusalem to the ends of the earth. Luke highlights Jesus’ promise (Acts 1:8) to the nascent community, which includes its witness in concentric circles emanating from Jerusalem (1:1-5:42) to Judea (6:1-8:1) to Samaria (8:1-40) and to the ends of the earth (9:1- 28:31). What Jesus began to do and teach in the Gospel (1:1), He will continue to do and teach through the Spirit-empowered witness of the early Church in various geographical areas. The narrative of the Jerusalem Council (15:1-35) directly follows the beginning of the Gentile mission (9:32-11:18) and the mission from Antioch to Asia Minor (11:19-14:28); it is followed by Paul’s missionary journeys in Macedonia and Achaia (15:36-18:17), Asia Minor (18:18-20:38), and Paul’s arrest and imprisonment (21:1-28:31). The first campaign in Antioch and Asia Minor (11:19-14:28) precipitated the conflict on the terms of admission for the Gentiles (Acts 15). Luke writes a narrative that depicts how the Christian campaign bursts through the narrow confines of Judaism, reaching out to include new persons at various locations in ever-widening circles.

Biography

Luke’s hinge (Acts 15) reveals three persons or groups involved in the Church’s leadership who will shift in Luke’s second panel. First, the initial portion of Acts narrates numerous stories surrounding Peter (58 references to Peter in 1:13-12:18).9 There are two references to Peter or Simeon in Acts 15, but in the second panel of Acts, Peter is never mentioned; either Luke does not know of Peter’s activity or consciously omits any further reference to him. In Luke’s hinge, both Peter and Paul are involved in the deliberation; however, after this narrative, Paul takes precedence (113 references to Paul); initially Paul and Silas convey the message to Derbe and Lystra (16:1-5).

Second, there is a noteworthy development in terms of “apostles and elders.” From 1:2-14:14, there are 23 references to apostle(s). Prior to the Jerusalem Council, Luke states that Paul and Barnabas appointed elders in each church (14:23). The hinge brings together both apostles and elders (six references to apostles, five of which are paired with elders). Foakes-Jackson notes, “It is noteworthy that we hear nothing of the Twelve as the ruling body of the Church.”10 Subsequently, the only reference to apostles is found in 16:4 where Luke mentions the decision by the apostles and elders in Jerusalem. With respect to elders, there are two further references in the latter portion of Acts (20:17—Ephesian elders; 21:18—all the elders present in Jerusalem).11 In Acts 20, elders (presbute/roi, 20:17) are also defined as overseers (e0pi/skopoi, 20:28) with a pastoral role, “keep watch . . . over the flock” (poimni/on, 20:28, cf. 20:29) with the complementary infinitive of purpose, “to shepherd” (poimai/nein) the Church of God (20:28).

Third, there is a transition in Acts between the respective role of James and that of Paul. Luke notes that the brothers12 of Jesus (including James) were waiting in the upper room for the promised Holy Spirit (1:14). In 12:17, Peter sends a message to James and the brothers—“evidently a person of such consequence that he needs no description.”13 In Acts 15:13, James emerges as “first among equals” (primus inter pares), as a leader and chief spokesman for the Council. Paul holds only a minor role in the deliberations while James’ position is major. In 21:18, James and the elders greet Paul and company and warmly receive them and their report about successful Gentile ministry. However, they also raise the caveat by Christian Jews about Paul’s relaxation of Jewish customs. They propose some measures of “damage-control” (purification, expenses, shaved heads of four men, 21: 23-24) to which Paul submits (21:26). Even though Paul yields to the social pressure of James and the elders, it makes no difference, for the Jews’ behavior towards Paul leads to his arrest (21:33-36). Paul’s role is major in his final campaign while that of James is lesser when Paul arrives in Jerusalem; even though Paul submits to James’ proposal, it fizzles. Instead of a peaceful resolution suggested by James, the narrative tells of a riotous mob (21:27-32) leading to Paul’s arrest and subsequent trial scenes.

Case Studies

Luke’s hinge (Acts 15:1-6:5) belongs to a coherent series of case studies in resolving conflicts that follows a pattern of: (1) conflict, (2) resolution, and (3) advance of the Christian message. Joseph Tyson provides a similar outline of: (1) peace, (2) threat, (3) resolution, and (4) restoration.14 My term advance is an extension of a resolution that Tyson calls restoration. Often, resolution is seen as the final goal of a conflict story; however Luke’s stories narrate that the process of conflict–resolution also leads to an advance through the strengthening of the Church and the numerical growth of believers. For example, the conflict related to Ananias and Sapphira’s hypocrisy is resolved through the death of both (5:1-10) and advances with respect to religious dread (5:11, 13), praise of the apostles (5:13), the continuation of signs and wonders among the people (5:12), and the numerical addition of believers (5:14). Luke’s adverb, “now more than ever” (ma=llon, v.14), points to the paradoxical multiplication of believers and the numbers of people who are healed and exorcised (5:15-17) to the extent that people believed that even Peter’s shadow might heal them (5:15).

Similarly, the divisive conflict surrounding the prejudice against Hellenistic widows is resolved by a communal ad hoc decision to appoint seven deacons to fairly administer the funds (6:1-6). In turn, this decision and its implementation leads to the advance of the Christian message since the apostles are free to concentrate their undivided attention to the “Word of God” (6:2). Luke notes the advance, “so the word of God spread,” that is linked with a rapid numerical growth of disciples in Jerusalem and the large number of priests that become obedient to the faith (6:7). Further, Steven, one of the appointed deacons (6:15), advances the Christian message through his person (“a man full of faith and the Holy Spirit,” 6:3), his miraculous activity (God’s grace and power, wonders and miraculous signs,” 6:8) and through his faithful and fearless witness to the hell-bent religious authorities (6:13-7:53).15

Likewise, a conflict arises about Paul’s credibility as a Christian witness (9:19b21, 26). To resolve the issue, Barnabas comes to Paul’s defense (9:27). Once Paul’s credibility is resolved in Jerusalem, Luke notes the advance through Paul’s early ministry of a bold witness, debate, peace, strengthening, and encouragement, resulting in the growth of the Church in numbers (9:31). The problem related to Peter’s table-fellowship with uncircumcised men (11:1-2) is resolved through the joint visions of both Peter and Cornelius (11:4-11), which is accepted by the apostles and brothers in Jerusalem (11:1, 18) when they state “God has granted even the Gentiles repentance unto life” (11:18). Luke records the advance, “The Lord’s hand was with them and a great number of people believed and turned to the Lord” (11:21). As is proposed in this paper, the same structure of conflict–resolution–advance of the Cornelius-episode is followed in 15:1-16:5.

In 18:24-28, Luke raises the problem of Apollos’ inadequacy that “he knew only the baptism of John” (18:25). Priscilla and Aquila resolve the issue when they explain to him the way of God more adequately” (18:26). Subsequently, Apollos’ witness advances the Christian message: “He was a great help to those who by grace had believed” and was vigorous in his proclamation and debate (18:27-28).

Theology

Luke’s hinge highlights the legitimacy of Gentile-inclusion; there are seven positive references to the Gentiles (Acts 15:3, 7, 12, 14, 17, 19, 23). Luke’s first panel prepares the reader for the theological and practical issue raised in the Jerusalem Council. Luke narrates the story of receptive Gentiles on the Day of Pentecost (2:5-12), the Ethiopian eunuch (8:26-40), Paul’s ministry to the Gentiles (9:15), and most importantly for Acts 15, the detailed Cornelius story (10:1-11:18). Acts 11:19-30 includes a substantial witness among the Gentiles at Antioch and is followed by Barnabas and Paul’s missionary tour in which Gentiles receive the Christian message (13:1-14:28), well expressed by the statement, “now we turn to the Gentiles” (13:46). Charles Talbert observes that “the extension of the gospel to the Gentiles is followed by an episode of Jerusalem approval.”16 The issue of Peter’s table-fellowship with Cornelius and its significance is thoroughly narrated; the various pericopes serve as introductory material for the issue of Gentile-inclusion, so important for Acts 15. In the process of debate, both Peter and James look to the precedent established through Peter. It is also important that during the Council there are two versions of the Jerusalem compromise (15:20, 29), reference to the decrees (do/gmata, 16:4) and one version in Luke’s “second-half” (21:25), again at Jerusalem. There are five references to (un)circumcision in Luke’s first panel (two of these refer to Abraham’s covenant—Acts 7:8), four in 15:1-16:5, and one reference in Luke’s second panel (21:21). Luke also refers to the Gentile ministry sixteen times in his second panel no longer as a question or theological issue but as a settled matter; the conclusion of Acts expresses the certainty that “God’s salvation has been sent to the Gentiles and they will listen” (28:28).

The entire process of conflict–resolution–advance of the Jerusalem Council (Acts 15) is pivotal for Luke in terms of geography, biography, history, and theology— specifically related to Gentile inclusion. Given the facts that Acts 15:1-16:5 is a detailed story that coheres with other similar case studies, that the Jerusalem Council occurs midway in the book of Acts, that chapters 10:1-14:28 are introductory to Acts 15, that the issue of Gentile-inclusion is resolved, that Acts 15 is pivotal in the book of Acts, that a ministry to the Gentiles has already been affirmed (13:47) with signs and wonders (14:3), and that the door of faith to the Gentiles has been opened (14:27)—all combine together to affirm that Luke wants his readership to look at both the pivotal decision of the Council and the instructive process by which a landmark decision was reached. Referring to the Apostolic Council, Hans Conzelmann states, “It is the great turning point, the transition from the primitive church to the ‘contemporary’ church.”17 The introductory chapters build with intensity to the summit meeting in Acts 15; a problem has been brewing, which deserves careful attention. As Dunn notes, “Luke had already prepared the ground to deal with this potential crisis.”18 Luke is concerned with the advance and victory of the Christian message in spite of the problems (internal and external) encountered by the Christian community. In the Acts 15 narrative, the issue of Gentile-inclusion is of such a magnitude that the Antiochene Church sends Paul, Barnabas, and others to Jerusalem to resolve the issue (15:2). And in Jerusalem, the apostles and elders felt that the problem was weighty enough to warrant looking into the issue, resolving, and communicating a decision.

II. The Various Elements of the Conflict (Threats)

Terms of Admission for Gentile Salvation–Circumcision

Conflict begins in Antioch by some men who came from Judea and taught in Antioch that circumcision of the Gentiles is the necessary requisite for salvation: “Unless you are circumcised, according to the custom taught by Moses, you cannot be saved” (15:1). The “practice of Moses” (tw=| e1qei tw=| Mwu+se/wv) refers to “the whole of the cultic law attributed to Moses,”19 and is extensively used by Luke.20 In 15:5, some Christian Pharisees in Jerusalem made the requisite even more pointed, “The Gentiles must be circumcised and required to obey the Law of Moses.”21 The implicit question is also present: Can Gentile Christians live among Jews without becoming proselytes? Later in the narrative, the Jerusalem compromise reveals the related issue of table-fellowship (15:20, 29) between Jews and Gentiles, expressed as Gentile concessions to Jewish sensibilities. The necessity of Gentile circumcision and keeping of the Mosaic Law are the presenting problems, noted early in the discussion, while the issue of table-fellowship is taken up in the decision and its formal expression. The problems concern personal and group identity and praxis.

Although not explicitly stated, the Jewish “hard-liners” possess a great deal of ammunition for their cause. The Torah expresses a categorical commitment to the practice of circumcision as a sign of covenant-relationship through Abraham’s example (Gn 17:9-14). Males who refused the sign were regarded as “cut off from the people of God” be they Jewish males, their immediate offspring, generations to come, aliens (Ex 12:44, 48) or purchased slaves; the physical sign was “everlasting” (17:13) that affected Jewish identity and praxis.22 The demand is categorical with no negotiating room. Support for circumcision could also be also garnered from the history of the Jews during the Maccabean revolt; the Syrians were committed to destroy Israel’s unique traditions, including the sign of circumcision (1 Macc 1:48, 60-61). During a prolonged military conflict, Mattathias and company “circumcised by force the children that were not circumcised” (1 Macc 2:46). Since the Syrians regarded circumcision as a capital offence, many loyal Jews lost their lives during the Syrian occupation. Further, from the witness of the four gospels, Jesus was circumcised (Lk 2:21) and made no comment in his ministry about the abrogation of circumcision.

The main conflict lies in the denial of salvation for Gentile believers who have not been circumcised and have not kept the Jewish Law and are thereby excluded from table-fellowship. Theological and practical issues are linked. The Jewish Christian group sees salvation in terms of exclusion—not inclusion. In Acts, the verb to save (sw/zein) is used fourteen times and the noun salvation (swthri/a; swth/rion) occurs seven times,23 and is augmented by numerous other terms of the salvific word-family. The salvific terms, so central for Luke, are comprehensive and relate to numerous benefits for the people of God. I suggest that salvation in the book of Acts involves a personal trust in the whole of the past Jesus-event (particularly the suffering, death, and vindicating resurrection of Jesus),24 a present and personal experience of the risen Jesus and attendant benefits, mediated through the Holy Spirit25 and a hope in a future consummation of salvation. 26 It is clear that Luke orients the community to the universal offer of salvation for all, irrespective of racial, ethnic, or religious limitations (2:21; 3:11- 12; 4:11-12). Thus, Luke uses exclusionary conflict stories to emphasize the universal appeal of salvation with all of its attendant benefits (10:1-11:18; 15:1-35).

Earlier, Peter’s introductory report of the Gentile Cornelius was met with praise by the apostles and brothers, “So then, God has granted even the Gentiles repentance unto life” (11:18). However, the hardliners were either ignorant of the event or detracted from its significance, since the Cornelius story took place years prior to the Council. Perhaps the argument was made that this was an anomaly, an ad hoc situation, a personal story, or an exception to the rule. Dunn notes, “Its strength had yet to be tested.”27 But what about Gentile conversion en masse? Previous narratives in Acts 13- 14 reveal Paul’s commitment to the Gentile ministry in Gentile areas and their joyous response:

· “the forgiveness of sins is proclaimed to you (Gentiles) . . . everyone who believes” (13:38-39)

· “we now turn to the Gentiles” (13:46)

· “I have made you a light for the Gentiles, that you may bring salvation to the ends of the earth” (13:47 from Is 49:6)

· “When the Gentiles heard this, they were glad and honored the word of the Lord; and all who were appointed for eternal life believed” (13:48)

· “a great number of Jews and Gentiles believed” (14:1)

· “how he (God) had opened the door of faith to the Gentiles” (14:27)

Thus, there is a cause–effect relationship between the “door of faith opened to the Gentiles” and the exclusionary attitudes of the Jewish hardliners in 15:1, 5.

Gentile Adherence to the Law

The Christian Pharisees in Jerusalem not only required circumcision but adherence to the Law as a corollary (15:5). As Barrett notes, “There would be no point in being circumcised and then neglecting to keep the Law.”28 The Law (no/mov) here signifies “the Law which Moses received from God.”29 From the Jewish perspective, circumcision and obedience go hand in glove; relaxation from circumcision is tantamount to rejection of Torah or “the Jewish way of life.”30 Christian Pharisees could hardly imagine that their trust in Jesus would also mean a suspension from obedience to the Law. Up until this point, commitment to the Law is presupposed in Luke’s earlier narratives. From the practical point of view, the Jewish mission would have failed if there was a clear abandonment of the Jewish way of life. Now, in a situation of conflict, “the community and its Head would be condemned from the very outset in their eyes. . . The practical consequences were naturally difficult in mixed congregations.”31

Table-Fellowship

Although table-fellowship was not part of the presenting problem, the compromise, in its three forms (Acts 15:20, 29; 21:25), reveals that table-fellowship between Christian Gentiles and Christian Jews was a practical issue. Just as Moses was linked with the practice of circumcision (v. 1) and the Law (v. 5), so Moses is drawn in with the issue of table-fellowship; “for Moses is being read” (v. 30) as support for the compromise (v. 29). In the introductory story of Cornelius, the initial critique from the apostles and brothers links the issue of circumcision and table-fellowship, “the circumcised believers criticized him and said, ‘You went into the house of uncircumcised men and ate with them” (11:2; emphasis added).

Expressions of Conflict

Luke expresses the conflict through numerous nouns and verbs, such as dissension (sta/siv) 32 and sharp debate (zhth/siv33 ou0k o0ligh/―litotes 15:2; see 14:27) in Antioch, and linked to “this controversial matter” (zh/thma) in Jerusalem (15:3) and “this matter/question” (o( lo/gov ou{tov, 15:6) and “much dispute” (pollh/ zhth/siv, 15:7). Together, the expressions reveal the turmoil caused by the hardliners. Through Peter’s speech, Luke expresses the demand as a “yoke (zugo/v) that we neither we nor our fathers have been able to obey” (15:10), which is also expressed in v. 28 as a “burden” (ba/rov).34 Luke also indicts the Jewish Christians for “challenging God” (“why are you challenging God?” ti/ peira/zete to\n qeo/n [15:10]).35 In 15:19, Luke (through James’ speech) understands that the exclusionary demand is a form of “harassment.”36 Luke uses two other verbs, which express the result of the hardliners’ demands: “they disturbed” (e0ta/racan) you and were “troubling (a0naskeua/zontev) your minds by what they said” (v. 24). Further, the narrative also repeats the verb, “to become silent” (siga=n [15:12-13]), which contrasts with the previous heated discussion. From the way that Luke constructs the narrative, the hardliners’ argument is not expressed other than the minimal references in 15:1, 5. Given the fact that Luke already knows the way in which the conflict was resolved, it is only natural that specific support from the hardliners receives only minimal attention. Obviously, there is much by way of argument and counter-argument that is unrecorded.

Threat to the Unity of the Christian Community and Its Leaders

Luke provides numerous summaries in the book of Acts, which are marked by an idyllic picture of unity (e.g., 2:42-47, 4:32-35, 5:12-14, 16:5). Tyson remarks, “For Luke, authentic Christianity is marked by peace and concord among the leaders and members.”37 Such unity is well expressed in 14:26-28. At the same time, Luke is realistic; this idyllic picture of the community’s life is often threatened. In terms of unity, the conflict also threatens to separate the apostolic leaders as well the two centers (Jerusalem and Antioch). How will Barnabas and Paul’s more liberal policy fare with the more conservative apostles in Jerusalem? And will there be division between the mother church in Jerusalem and the daughter church in Antioch to the extent that there will be two headquarters with two separate missions, one for the Jewish Christians and one for the Gentile Christians? The threat and danger are real. Can both Christian groups be Christians together? And if so, what are the important considerations?

III. The Dynamics that are Part of the Resolution

The dynamics for successful decision making are both multiple, interdependent, and instructive for Luke’s readership. They include

Sensitivity to the Divine Initiative

Luke consistently affirms the divine initiative in Gentile-inclusion38 noted through verbal forms:

· “everything God had done through them” (o#sa o( qeo\v e0poi/hsen met 0 au0tou= [15:4])

· “God made a choice among you that the Gentiles might hear from my lips the message of the gospel and believe” (e0n u(mi=n e0cele/cato o( qeo\v dia\ tou= sto/matov mou a0kou/sai ta\ e1qnh to\n lo/gon tou= eu0 aggeli/ou kai\ pisteu=sai [15:7])

· “God, who knows the heart witnessed (guaranteed) to them” (o( kardiognw/sthv qeo\v e0martu/rhsen au0toi=v [15:8])

· “[God] by giving the Holy Spirit to them just as he did to us” (dou\v to\ pneu=ma to\ a#gion kaqw\v h(mi=n [15:8])

· “He made no distinction between us and them”39 (ou0qe\n die/krinen meta/cu h(mw=n te kai\ au0tw=n [15:9])

· “[God] by cleansing their hearts by faith” (th=| pi/stei kaqari/sav ta\v kardi/av au0tw=n [15:9])

· “the miraculous signs and wonders God had done among the Gentiles through them” (o#sa e0poi/hsen o( qeo\v shmei=a kai\ te/rata e0n e!qnesin di 0 au0tw=n [15:12])

· “God at first showed his concern by taking from the Gentiles a people for his name” (o( qeo\v e0peske\yato labei=n 40 e0c e0qnw=n lao\n tw=| o)no/mati au0tou= [15:14])

· The quote from Amos uses three verbs in four expressions in the first person singular, where God is the speaker: “I will return” (a0nastre/yw); “I will rebuild” (a0noikodomh\sw) twice; “I will restore” (a0norqw/sw [15:16]). Further, the last line also affirms the divine initiative, “says the Lord who does these things” (le/gei ku/riov poiw=n tau=ta [15:17])

Thus, Luke provides a total of fifteen expressions that affirm the divine initiative and activity in Gentile-inclusion. Luke intends that his readers sense that human figures, engaged in resolving the conflict, are acknowledging God’s prior initiative and action. They are in fact “catching up” with God’s purposeful activity and ought to raise the question, “Where is God already at work in our community?”

Discernment of Saving-Activity of God

Whereas the hardliners argued for an exclusive salvation (v. 1), Luke argues for an inclusive salvation, “No! We believe that it is through the grace of our Lord Jesus that we are saved,41 just as they (Gentiles) are” (v. 11). The reversal of language is both surprising and revealing; it is a new paradigm that the Gentile’s salvific experience becomes the gauge by which Jewish Christians are measured. Johnson notes, “God uses the salvation of the Gentiles to reveal to Jewish believers the true ground of their own salvation.”42

While Luke summons his readership to reflect divine-inclusion, he is also committed to the essentials (e.g., trust in the grace of the Lord Jesus [15:9, 11], the gift of the Holy Spirit [15:8], turn to God [15:19], and salvation [15:11]). However, there is a freedom from a binding “nonessential” (i.e., circumcision). Due to Luke’s irenic tendencies and the burgeoning Gentile mission (14:1-28:31), he wishes that his readership adopt an open stance, emphatically expressed in the closing verses, “Therefore I want you to know that God’s salvation has been sent to the Gentiles, and they will listen” (28:28). Luke does not advocate a “replacement theology,” wherein Christianity replaces Judaism or that the Church is a “completed Judaism.” Instead, the unfolding mission couples Jewish restoration with the Gentiles, called by God’s name— but not converts to Judaism (vss. 16-19); the divine initiative includes both groups. Thus, the community should not make it difficult for Gentiles, who turn to God; in no way should Gentiles be required to be circumcised (v. 28).

Luke’s book of Acts reveals his fundamental commitment to the mission of offering salvation to all. To those who are preoccupied with the immediate restoration of the Kingdom to Israel (1:6), they are called to the world-wide missionary task, “you shall be my witnesses” (1:8), subsequent to their empowerment by the Holy Spirit. Pentecost assures the nascent community of the Spirit’s manifest presence and power. To those who might be discouraged that the Parousia would ever occur, they are promised that the Lord Jesus would return in the same fashion as they saw Him go into heaven (1:11). In between Pentecost and the Parousia (or “the times of regeneration” in 3:20), the Church is Spirit-empowered for responsible and faithful witness. Jesus would “continue to do and to teach” (1:1) through the witness of the ever-expanding Church.43 Further, it is significant that Luke concludes his book in an open-ended fashion, crowned by God’s salvation, the Kingdom of God, and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ (28:28-30). Graham Twelftree notes that Luke “expects readers to take up in their lives what has become Paul’s story. Though Paul dies, he lives in their ministry; the end of his mission is the beginning of theirs—to the ends of the earth (1:8).”44 Through people, the descriptive narrative of Jesus’ saving-activity becomes the prescriptive “marching-order” for the Church of Luke’s day. God’s saving activity for all is all-inclusive. The witness of Jesus is to be constantly on the move, never satisfied with the status quo of a past era, geographical place, or an exclusionary group. Good things happen when the Church is scattered even as a result of persecution (8:1―Samaria).45

Clarion Call to Unity

Unity is revealed through the numerous people involved in the deliberation who come to a common consensus:

· Apostles and elders (15:2, 4, 6, 22, 23)

· Apostles (15:33)

· Church (15:3, 4, 22)

· Whole body of members (plh=qov,46 15:12, 30)

· Brothers (15:1, 3, 7, 13, 22, 23 twice, 32, 33)

· Men (15: 7, 13, “leading men” in 22 twice, 25)

· Certain ones (15:1, 2, 5, 24)

· Key individuals by name (Paul and Barnabas―15:2 twice,12, 22, 25, 35), Peter/Simeon (15:7, 14), James (15:13)

· Prophets (Judas and Silas, 15:32)

· Divine persons (God―15: 4, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14, 18, 19; Lord Jesus―15:11, 26; Holy Spirit―15:8, 28)

The numerous “stake-holders” (both human and divine) affirm a communal search for the will of God in this particular conflict; the forum demonstrates respect for people holding different values and opportunity is given for personal expression from all parties.47 It implies a shared willingness to find common ground. The engagement and agreement by the Council and all persons are critical. The process uses the leadership structures that were somewhat formalized by this time, specifically with the repeated mention of the apostles and elders and an apostolic leader (James). To be sure, within this group, certain individuals “carry more weight,” but this does not negate the communal participation and approval of the decision. Although James’ argument and decision are climactic, the entire church is engaged in the decision and its implementation (15:22).

For Luke, unity is essential for communal life and witness and is well expressed by one of Luke’s favorite terms, “of one accord” (o(moqumado/n, v. 25). The term is found almost exclusively in Acts48 and is frequently found in Luke’s summaries (Acts 1:14, 2:1, 2:46, 4:24, 5:12).49 Another related Lukan expression (not found in Acts 15) is “to be\come together” (“at the same place,” e0pi\ to\ au)to /),50 which also is found in Luke’s summaries (Acts 1:15; 2:44, 47; 4:26). The terms reflect Luke’s idyllic and idealized portrait of the early Christian communities. Tyson links these expressions with the “internal harmony of the community.”51 In Acts 15, the expression “of one accord” means that the decision and its implementation express the idea of harmony, peace, wholeness, and agreement by all the parties concerned in the conflict. No word of dissension is heard at the time of the decision or the letter’s composition. Delegates from the Jerusalem Council are sent to Antioch and then return to Jerusalem; this course of action highlights the continuing positive relationship between the motherchurch in Jerusalem and the daughter-church in Antioch. Further, accord is well expressed by the three-fold use of the verb, “to think, seem, consider” (doke/w) with a following infinitive. BDAG translate the impersonal use of the verb by “it seemed best to.”52

· v. 22: “it seemed best (e1doce) to the apostles and elders . . . to send (pe/myai).”

· v. 25: “it seemed best (e1doce) to us . . . to send (pe/myai).”

· v. 28: “it seemed best (e1doce) to the Holy Spirit and to us . . . not to lay upon (mh\ e0piti/qesqai).”

This is not authoritarian language, but reasoned communication that is communal in nature, involving the whole church, its leadership, and the Holy Spirit. The decision does not read “as a power play by one faction dictating its will to the rest.”53 It is also interesting that there are only two imperative verbs in the entire story (“listen to me” [a)kou/sate mou], v.13; “farewell” [e1rrwsqe]); therefore, the decision is set within the context of politeness, respect, and fairness.

The Role of the “Story”

Shared experiences play an important role in resolving the conflict. The shared stories are not incidental or accidental but are vital for Luke’s purpose. Stories reveal a “lived theology.” In the broader Lukan context, the story of Jesus (Luke) is incomplete without the various stories of individuals, who advance the Christian message (Acts).

Barnabas and Paul’s story is initially introduced in Acts 14:27-28, as a precursor for the Jerusalem Council. The text states that the pair arrived in Antioch and stayed there a long time. There are four stories told using identical or similar language:

· In Antioch, upon their arrival, Luke states that they narrated their story to the “gathered church” and “were rehearsing all that God had done through them and how he had opened the door of faith to the Gentiles” (a0nh/ggellon o#sa e)poi/hsen o( qeo\v met 0 au0tw=n kai\ o#ti h1noicen toi=v e1qnesin qu/ran pi/st ewv[14:27])

· In Phoenicia and Samaria, the pair are “describing the conversion of the Gentiles (e0dihgou/menoi th\n e0pistrofh\n tw=n e0qnw=n)”; the report being met with great joy (15:3)

· In Jerusalem, “they rehearsed everything God had done through them” (a)nh/ggeilan te o#sa o( qeo\v e)poih/sen met 0 au0tw=n [15:4])

· In Jerusalem, during the deliberations, the pair are “telling the story about the miraculous signs and wonders God had done among the Gentiles through them” (e0chgoume/nwn o#sa e0poi/hsen o( qeo\v shmei=a kai\ te/rata e0n toi=v e1qnesin di ) au0tw=n [v. 12])

All four verses include a verb of “telling” (a0nagge/llw used twice), the substantive, “all that” (o#sa) is used three times, the verb “to do” (poie/w) and its subject “God” are used three times, the prepositional expression “with them” (met 0 au0tw=n) or “through them” (di ) au0tw=n) is used three times and there is mention of Gentiles (e!qnh) in three verses.

Luke intends that his readers appreciate the value of the pair’s shared experience. He stresses the happy welcome of the pair in Phoenicia and Samaria and Jerusalem (vss. 2-4). Although Peter and James are more prominent in the Council itself, the pair’s story provides a steady support both before and during the Council for the inclusion of the Gentiles.54 The pair’s experiential voice is not too suppressed or minimized; the shared story needs to be told and well-received. The repetition of the story possesses an implicit power to convince. In these texts, no propositional or theological argument for the inclusion of Gentiles is offered. “Their position is communicated best by the recountal of their experience of God’s work.”55

The pair’s “story” is not only their story alone, but a story which must also become a communal story and part of the corporate memory of the Council. The shared story must also be interpreted by the community as solid evidence for the gathered community. The narrative is a story about what God has done through people on behalf of the Gentiles. In 11:17, Peter had raised the rhetorical question, “Who was I to think I could oppose God?” The Jerusalem community must ask the same questions, “Who do we think we are who could oppose God’s patent saving-activity for the Gentiles?” “How can we demand the Jewish way of life from those whom God has so clearly included?” In the shared story of God’s activity, both the Jewish and Gentile persons and groups find their identity, meaning, and calling to be Christians together. The shared memory of the past also contains an implicit meaning for both the present deliberations of the Council and the future of the community as “the opened door of faith to the Gentiles” (14:27) opens even in wider dimensions in the second panel of the book of Acts.

Peter’s story is also an important part of the Council’s process. While the pair’s story was general in nature, Peter’s story is particular in the Cornelius episode (Acts 10:1-48) and its retelling in Jerusalem (11:1-17) prior to the Council. In the Council (Acts 15), this is the third telling of the story in summary form by both Peter and James; Peter’s introductory statement, “you know” (e)pi/stasqe) affirms that the audience is already familiar with Peter’s experience. Peter’s statement, “some time ago” (lit. “from the days of old” [a0f 0 h(merw=n] v. 7), refers to the Cornelius episode (esp. 10:44-46; retelling in Acts 11:1-17). What did the Cornelius story convey? The story highlighted the divine activity for Gentile inclusion, by orchestrating two complementary visions, one to Peter and the other to Cornelius, in different places and its climax when the two persons come together. While Peter’s vision was first puzzling to him, he understands the vision’s significance when he encounters Cornelius and his friends. He now knows that he is not to discriminate (10:28—“I should not call any man impure or unclean”; see 11:9), that “God does not show favoritism but accepts men from every nation” (10:34), the Holy Spirit had been poured out even on the Gentiles (10:45), and that God has cleansed their hearts by faith (15:9)—without adopting the Jewish way of life, including circumcision. Thus, the story becomes a “classic prototype,”56 by which Peter transposes a personal story into a vigorous theological affirmation.

God is the subject of each of the verbs in Peter’s story, and thus, Peter also witnesses with the pair as to the activity of God. At the same time, the tellers of the stories make it clear that this is their own story of God working through them or with them. The conflict arose in Jerusalem over the issue of table-fellowship with the Jewish Peter and the Gentile Cornelius (“You went into the house of uncircumcised men and ate with them” [11:3]) and concludes with the apostles’ and brothers’ affirmation that “God has granted even the Gentiles repentance unto life” (“without circumcision” [11:18]). The personal narratives of Barnabas, Paul, and Peter witness to a united and shared story that contributes to a common affirmation by the entire Council. Three stories coalesce into one common witness that divine grace, met with human trust, is the only means of salvation for both groups (“we in just the same way as they” [15:11]). It leads to Peter’s summative statement of corporate belief, “We believe” (15:11).

A subtext may be inherent in Luke’s narrative of Peter’s story. Peter had been a reluctant missionary in his vision. In the vision Peter was strongly “religious” in his emphatic refusal, “No way Lord” (Mhdamw=v ku/rie [10:14; 11:8]),57 which may be the reason for why the vision of the sheet occurred three times (10:16). His prejudicial attitude needed to be overcome and is done so that he learned and lived a new way of thinking. Correspondingly, the hardliners express exclusionary attitudes that Peter had once felt. Thus, the hardliners who share affinity with Peter’s initial reluctance may be encouraged to overcome their own prejudice as well.

James, as the leader of the apostles and brother of Jesus,58 puts his stamp of approval on Peter’s experience with Cornelius and its bearing upon the present decision as well as its future implications (15:14). There are two aorist tenses, which refer to a particular point in time with respect to the Cornelius-story: “Simeon rehearsed” (e0chgh/sato) and “God concerned himself with” (e0peske/yato).59 The adverb, “first” (prw=ton) links back to Peter’s speech as well (“some time ago” [a0f 0 h(merw=n] v. 7). James’ argument affirms Peter’s experience and its clear announcement of the divine purpose of “taking from the Gentiles a people for himself” (15:14). In the expression, “from the Gentiles, a people for his name” (e0c e)qnw=n lao\n tw=| o)no/mati au0tou=), there is a contrast between the “Gentiles” and “a people.” Hitherto, the Gentiles (“no people”) did not constitute God’s people by way of race or racial mark. However, God has done the paradoxical thing in the Cornelius story, to make “a people” for his name (i.e., “for himself”), from what was regarded as no people.60 Thus, James along with Peter confirm that God’s purpose of calling the Gentiles parallels God’s calling of the Jews; they belong together. Peter’s story has convinced James of the implications of Peter’s precedent.

Awareness of the Holy Spirit

Luke emphasizes the Holy Spirit in the process in the deliberations of the Jerusalem Council. There are two explicit references to the Holy Spirit (15:8, 28). In 15:8, Peter narrates the thrust of the Cornelius story to stress the comparison between Cornelius and the apostles in their shared experience of the reception of the Holy Spirit:

· “by giving the Holy Spirit to them just as he did to us” (dou\v to\ pneu=ma to\ a#gion kaqw\v kai\ h(mi=n [15:8])

· “the Holy Spirit came on all who heard the message” (e)pe/sen to\ pneu=ma to\ a#gion e0pi\ pa/ntav tou\v a0kou/ontav to\ lo/gon [10:44])

· “that the gift of the Holy Spirit had been poured out had been poured out even on the Gentiles” (o#ti kai\ e)pi\ ta\ e!qnh h( dwrea\ tou= a(gi/ou pneu/matov e0kke/xutai [10:45])

· “They have received the Holy Spirit just as we have” (oi#tinev to\ pneu=ma to\ a#gion e!labon w(v kai\ h(mei=v [10:47])

· “the Holy Spirit came on them just as he had come on as at the beginning” (e)pe/sen to\ pneu=ma to\ pneu=ma to\ a#gion e)p ) au)tou\v w#sper kai\ e)f 0 h(ma=v e)n a)rxh=| [11:15])

· “God gave them the same gift as he gave us” (th\n i!shn dwrea\n e!dwken au)toi=v o( qeo\v w(v kai\ h(mi=n [11:17])

Four of the six references draw comparison between the experience of Cornelius and friends with the event of the earliest community on the Day of Pentecost (“All of them were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit was enabling them” [kai\ e)plh/sqhsan pa/ntav pneu=matov a(giou= kai\ h!rcato lalei=n e(te/raiv glw/ssaiv kaqw\v to\ pneu=ma e0di/dou a)pofqe/ggesqai au0toi=v] 2:4). The experience of Cornelius and his friends’ “speaking in tongues” (10:46) also provides a tangible link with the Day of Pentecost. Luke’s readers understand that the brief references in Acts 15 to the coming of the Spirit upon Cornelius and friends (Acts 10-11) are of one piece with the recipients of the Spirit in Acts 2:1-4. Dunn notes, “As elsewhere in Acts, the Spirit is the central feature in the process of conversion-initiation,”61 understood by Dibelius as a “regularizing tradition ‘of a good while ago’—a classical meaning.”62 When previously questioned as to why Peter shared table-fellowship with uncircumcised Gentiles, Peter substantiated his freedom through the shared experience of the Spirit in his appeal to the Pentecostal event. As a result of the Spirit’s activity in both instances, the apostles and brothers had concluded that God was now granting life to the Gentiles on the basis of faith (11:18).

Luke also forges an implicit link with the Holy Spirit, expressed through Barnabas and Paul’s story of “signs and wonders” (shmei=a kai\ te/rata [15:12]).63 This is a favorite Lukan expression to refer to the tangible means by which God witnesses to the Jesus-event and is often found in Luke’s summaries.64 Signs and wonders are associated with the means by which God witnessed to Jesus being the Christ (2:22); the common life among believers (2:43); the prayers of the early community (4:30-31); extensive healings (5:12); the empowerment of Stephen, “full of grace and power” (6:8); the ministry of Philip (8:4-8); and the witness of Paul and Barnabas (14:3). In Acts 15, one of the “signs and wonders” certainly refers to the coming of the Spirit upon Cornelius and friends. For Luke, the manifest presence of God is itself a form of preaching; “signs and wonders” elicit conversion (2:37-42), “fear and faith” (2:43), a powerful shaking of a physical place and the fullness of the Spirit (4:30-31), “fear” (5:11), “togetherness” (5:12), attraction, revulsion (fear), and multiplication (5:13-16), hostility (6:9), “joy” (8:8), division, and further evangelization (14:2-6). Just as verbalized preaching elicits a complex of responses, the same can be said about the preaching role of signs and wonders; they both attract and repel people, who are either predisposed to reception or rejection of the Jesus-event. For Luke, the reception of the Spirit is manifest and is recognized by others, who are assured of their new life and empowered for the witness of their new life. Luke would have his readership be people of the Spirit, whose lives are marked by faith, signs, and wonders, even as they wrestle with particular conflicts in their communities. The shared recognition of the work of the Spirit in different lives is critical for the apostolic decision.

Luke also says that the Holy Spirit is active in the decision-making process (15:28), “it seemed best (e!docen)65 to the Holy Spirit and to us.” Who did it seem best to? In verse 22, it applies to the apostles, elders and the entire church, in verse 25 it is “to us,” and in verse 28, it refers “to the Holy Spirit and to us.” In the first two occurrences, it refers to the selection of certain men to carry the decision by letter to Antioch; the third use of the verb refers to the decision itself (v. 28). By the similar construction of the three verses, it is reasonable to conclude that the people and their leadership sensed that the Spirit was at work in the decision to send certain people to convey the decision as well. Conzelmann states, “This verse contains the Lukan concept of church and Spirit.”66 The text suggests the close engagement of the human and the divine in much the same way as the commission of Barnabas and Saul, when the Holy Spirit spoke through prophets and teachers as to the selection of the pair “for the work which I have called them” (13:2). Through the entire process, the divine and the human work in tandem. Since the Spirit was active among the Gentiles (notably in Cornelius) even before an apostle arrives and since the Spirit was at work in Gentile conversion (Acts 13-14), then the Spirit is also at work in helping the Jerusalem church and its leaders to enlarge their ways of thinking, feeling, and discerning, “so they can participate in the world of God’s reign—the world of the Spirit’s power—a world, not limited by a particular set of social, ethnic or religious prescriptions.”67

Readers are not told how the Spirit made its will known; it is interesting that Luke records no charismatic gifting in the Council’s deliberation (e.g., a prophecy or vision), simply the statement that the Council that is genuinely open to God’s will, can generate such an important decision that is inspired by the Holy Spirit. The Spirit’s power is evident in concrete human activities, here in the context of sharing in the stories of others, Scripture, deliberation, debate, compromise, decision making, and communication. The world of the Spirit is not to be isolated from human thinking, feeling, and acting, especially when there is a commitment to be Christians together.

The Role of Scripture

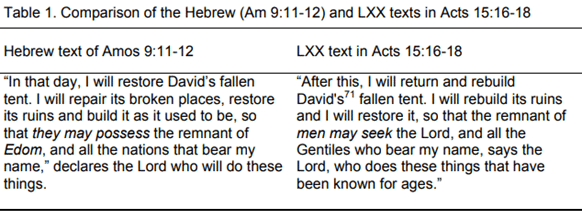

Luke also emphasizes the Scripture as a means by which important decisions are made.68 The text says that the Scripture agrees (sumfwnou=sin) with the narrative/experience of Gentile inclusion (15:15). As Johnson notes, “He does not say, ‘This agrees with the prophets,’ but ‘The words of the prophets agree with this.’”69 It is quite a reversal, similar to the way in which the Gentiles’ experience of salvation is the gauge by which Jews are measured (v. 11). Current experience finds support in the sacred text. Thereupon, James appeals to the LXX of Amos 9:11-12 to support the new experience.70 The Hebrew and LXX text of Amos 9:11-12 are at variance.

The Hebrew text says nothing about Gentile inclusion in the people of God but affirms that God will restore David’s fallen tent, “so that they may possess the remnant of Edom and all the nations that bear my name.”72 However, the LXX suggests the inclusion of other people and nations, “the remnant of men may seek the Lord.” It appears that the LXX reads “they may possess” (MT w#ryy) with “they may seek” (w#rdy) and “Edom” (Mwd)) with “men” (Md)) as the basis for its translation. The similarity of sounds of the two pairs no doubt caused the confusion of translation with an addition or transposition of a Hebrew radical. Thus, the LXX text affirms the missionary message of the Old Testament with the inclusion of the Gentiles. James’ argument from the Old Testament is clearly at odds with the Jewish Christian critique of verses 1, 5. On Luke’s use of Amos 9:11-12, Robert Wall suggests, “Gentile conversion does not annul God’s promise of a restored and redeemed Israel, but rather expands it; nor does faith (rather than Torah observance) as the condition of Gentile conversion contradict God’s plan of salvation, but rather confirms it. The second half of Acts provides a narrative that supports and explains this theological consensus reached at Jerusalem.”73

The Spirit is at work in Luke’s reinterpretation of the Amos text. “Once again, we cannot fail to be impressed by the extent of his sources and his ability to make effective use of his scriptural material.”74 As John Christopher Thomas states, “It appears that the experience of the Spirit in the community helped the church make its way through the hermeneutical maze.”75 Thus James’ appeal to an Old Testament precedent clearly “trumps” the Jewish–Christian precedent.

New Testament writers, such as Luke, possess five important sources that interact with each other in a dynamic way: (1) the experience of the person and ministry of Jesus, (2) the believing community, (3) stories, (4) the Old Testament, and (5) the interpreting Holy Spirit. The personal and communal experience of the early Christians with Jesus coupled with the interpreting person of the Holy Spirit gave them the clue to understanding and interpreting the Old Testament in a community context. “This approach does make room for illumination in the Spirit’s work, but it includes a far greater role for the work of the Spirit in the community as the context for interpretation, offering guidance in the community’s dialogue about the Scripture.”76 The use of Scripture is also noted in 15:21, “For Moses has been read in every city from the earliest times and is read in the synagogues on every Sabbath.” Mention of the Scripture, including Amos and Moses, here paves the way for the decisive prescription that follows (15:19-21). When the Scripture dialogues with present experience (personal and corporate), then the interpreting Spirit allows for a fresh reinterpretation of Scripture, since God continues to reveal Himself in the narratives of His people.

Decision with Compromise

The communal search for the will of God leads to a consensus with compromise so that Christian Jews and Gentile Christians can be Christians together. If the community fails to make a decision or makes a decision without compromise, the consequences would no doubt be negative. Indecision would lead to confusion and divisiveness; if there is no compromise, the backlash from the Jewish Christians might be substantial. If there was a casual or offhanded dismissal of the problem, then the failure to deal with the issue might well lead to increased tension, demoralization, or a deadly festering.

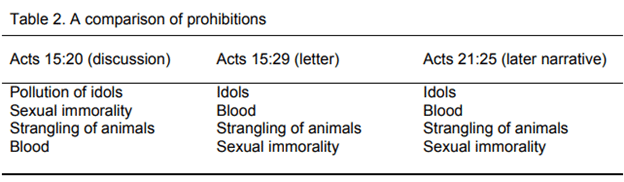

James’ speech begins with the logical result, “therefore” (dio/) to be drawn from the preceding discussion and is followed by his statement, “It is my opinion/judgment” (e)gw\ kri/nw [15:19]). Their shared experience is finally what matters most. Both groups must give and take so as to create a consensus that will mean a “win–win” decision for both groups; the voice of each group has been heard and respected. Consensus is highlighted in 15:25, “So we all agreed.” The final decision does not come by way of advice or suggestion; the decision stands good since it is authorized by the Jerusalem Council (leaders and church). The decision is made from the Jewish perspective as to: (1) how Jews are to celebrate Gentile inclusion based on divine grace and Gentile faith, (2) how Jews are not to harass Gentiles (third person in 15:19) and how the Jews are not to burden “you” (Gentiles [second person in 15:28—Gentiles in Antioch]) with anything more than some essentials. The Gentiles are to be sensitive to Jewish sensibilities. Since there are at least three versions77 of the decision, discussions abound as to the exact minimal restrictions that the Gentiles must concede and their nature, ritual, moral, or a combination of both.

Charles Savelle, along with others, provides extended discussion for each of these terms,78 which lie outside the focus of this essay. It is unlikely that Luke would have concerned himself with minute distinctions between ritual and moral stipulations. Suffice it to say that the items on the list are practices that would have been abhorrent to Jewish Christians: meat that had been offered to idols (pagan worship), sexual immorality (obvious), and the eating of meat of animals that had been strangled, since the blood was still in the meat. Since blood was associated with life, it was reserved for God alone (Lv 17:10-12). This concession represents the will of the Spirit and these stipulations are not overly burdensome for the Gentile (15:28). Even though the restrictions are labeled as “essentials,” they are not “essential for the salvation of the Gentiles” (15:11); they are “essential” for table-fellowship between Christian Jews and Christian Gentiles. Dunn calls them “minimum terms for mutual recognition and association . . . rules of association.”79

The Council tries to make things uncomplicated for the Gentiles (15:19, 28). The Jews are to accept Gentile salvation without circumcision and the Jewish way of life, while the Gentiles concede to restrict their behavior that would be offensive to Jewish Christians; an inclusive community will lead to a common table. Indeed, the initial accusation from “apostles and brothers” to Peter, was directed to Peter’s table-fellowship with uncircumcised Gentiles (Acts 11:3). The decree concludes with the statement, “If you keep yourselves free from such things, you will do well” (15:29). It suggests that Gentile sensitivity to Jewish sensibilities would be in concert with the will of the Holy Spirit and be relationally beneficial for the Jerusalem church and Jewish Christians. Talbert observes that “although Gentiles are free from the Law in the sense of ethnic markers like circumcision, they are expected to refrain from selected things required of resident aliens in Leviticus 17.”80 Craig Blomberg notes that the four abstentions are of an ad hoc nature81 and is supported by Weiser’s understanding of them as “a cultural phenomenon.”82 Luke’s later narrative of Paul also reflects such sensitivity to Jewish concerns: Paul circumcises Timothy (16:3), Paul takes a Jewish vow (18:18), continues to quote the Law (23:5), and shares in the purification of a group of Jewish men (21:23-26). He remains a faithful Jew, keeps the Law, and does not dissuade other fellow Jews from keeping the Law.

Clear Communication by Letter and Supporting Emissaries

The language of the letter is reciprocal and collegial. It is noteworthy that Barnabas, Paul, Judas, and Silas (both prophets) were not entrusted with the oral report of the decision alone. Although Barnabas and Paul (with others) were sent from Antioch to Jerusalem with the question, they are not the sole bearers of the decision. The decision is formalized into a letter from the Jerusalem Council to the Antiochene church; the four men serve a supportive role in communicating Jerusalem’s authoritative decision. The letter’s bearers could no doubt complement the contents or answer possible questions from the readers. The worth of the four is stated; Barnabas and Saul are worthy in that they have risked their lives for the Christian message, while Judas and Silas are identified as leading men (15:22, 25-27) and prophets (15:32). They will verbally confirm what the letter says, (lit.: through a word re-announcing the same things” [dia\ lo/gou a)pagge/llontav ta\ au)ta/]). Perhaps the Jerusalem Council thinks that since the Antiochene church would already know where Barnabas and Paul stood on the issue, a verbal report alone would be clearly biased in nature.

IX. The Ways in Which the Process Advances the Christian Message

The various aspects of the resolution process lead to a warm reception and a happy advance of the Christian message.

Joy

Upon receipt of the letter and its public reading, the Antiochene community (plh=qov) “rejoiced for the encouragement” (e)xa/rhsan e)pi\ th=| paraklh/sei [15:31]) that the letter brought. Evidently, they were hoping not only for a resolution but for a decision that they wanted. The original conflict in their community did not arise from within the community but from some unnamed individuals who had come from Judea (15:1).

Encouragement and Inner Strengthening

Joy is linked with “encouragement” (para/klhsiv) that the letter brought and is linked to the active role of two prophets, who “said much to encourage83 and strengthen the brothers” (dia\ lo/gou pollou= pareka/lhsen tou\v a)delfou\v kai\ e)pesth/rican [15:32]). Doubtlessly, the community is relieved that their identity and practice are confirmed both by the letter and its emissaries; Gentiles are glad to make accommodation to Jewish Christians so that they might live together and share table-fellowship. In addition, the community is also at peace since they send the two prophets back to Jerusalem “with peace” (met 0 ei0rh/nhv [15:33]). While the prophets report back to the Jerusalem community, Paul and Barnabas, with many others remain in Antioch, “teaching and preaching the word of the Lord” (dida/skontev kai\ eu0aggelizo/menoi . . to\n lo/gon tou= kuri/ou. [15:35]) for a significant period of time. No doubt, this extended time provided opportunities for further dialogue, input, reflection, and questions (implications or intimations).

Further Success of the Christian Message

Advance is also noted in the next two paragraphs (15:36-41, 16:1-5). Both paragraphs introduce the narrative of 16:6-18:22, which extends the mission into Macedonia. Even though Paul and Barnabas experience a painful separation, there is still an advance of the Christian message. Barnabas and Mark go to Cyprus, while Paul and Silas travel to Syria and Cilicia, “strengthening” (e)pisthri/zwn [cf. the same verb in 15:32 of Judas and Silas84]) the churches (15:41). Paul then retraces his steps on his first missionary journey—in Derbe and Lystra (16:1-5) before the more extensive journeys unfold into Europe. Talbert notes, “Nothing can stop the gospel, not even divisions among missionaries.”85 Two items stand out: (1) Paul’s circumcision of Timothy, and (2) Paul’s delivery of the Council’s decisions. Since Paul has lost Barnabas as his companion, he enlists Timothy to accompany him for his subsequent missions (16:3). In view of the fact that Timothy is half-Jewish and half-Gentile and that his uncircumcised Jewish status would be offensive to the Jews in that region, Paul circumcises Timothy (16:3). Timothy’s circumcision appears to be motivated by expedience, “to make an honest Jew of him,”86 just as Paul is an “honest Jew.” In the case of a mixed-marriage, Jewish identity appears to have been transmitted through the mother and Luke makes a point of noting that Timothy’s mother87 was a believer herself (16:1); the practice is assumed in 16:1-3. The Jerusalem Council had determined that circumcision was unnecessary for Gentile salvation, but the deliberations suggest that Jews would continue to practice circumcision and the Jewish way of life. Even though Paul’s ministry would be primarily Gentile in scope, he still was driven by a missionary impulse to his own people. An uncircumcised Jew would have been offensive to Jews in Jewish synagogues; thus, Paul removes a potential roadblock that would hinder his proclamation. From Luke’s perspective, Paul’s circumcision of the half-Jew Timothy would serve to negate the later charge leveled against Paul in Jerusalem: “you teach all the Jews . . . to turn away from Moses, telling them not to circumcise their children or live according to our customs” (21:21). This is supported by the fact that in the same paragraph (21:20-25), the Jerusalem compromise is mentioned (21:25).

In 16:4, Paul delivers the decisions from the Jerusalem Council (“they delivered the decisions reached by the apostles and elders in Jerusalem for the people to obey”). The word decisions (do/gmata) belongs to the same word family as the repeated verb, “it seemed best to” (dokei=n) of 15:22, 25, 28 and clearly relates to necessary behavior growing out of the Jerusalem Council; the decisions are formal and cannot be regarded as mere suggestions or advice. Originally, the extent of the Council’s decision involved Antioch, Syria, and Celicia (15:23), but now the decisions extend beyond these places.

Numerical Growth

Luke makes another summary statement88 in 16:5, which highlights the advance of the Christian message as a result of the Jerusalem Council: “So the churches were strengthened in the faith and grew daily in numbers.” The imperfect verbs “continued to be strengthened” (e)sterou=nto) and “continued to grow” (e)peri/sseuon) affirm the ongoing growth in the community’s inner life and numerical growth.

IV. Implications

Although Luke does not definitively voice his opinion or speak in his own name, he does provide a skillful, artful, pivotal, and instructive episode of the Jerusalem Council that serves as the hinge for the book of Acts. It is a theological narrative that says much about the joint involvement of the divine and the human, as the community of faith seeks to discern God’s will in changing circumstances. Luke provides sufficient detail as to the nature and elements of the conflict that could have been disastrous for the early Church: terms of admission for Gentile salvation—circumcision, exclusionary demands, the role of the Law, table-fellowship, and threats to the unity of the Christian community and its leaders. In his narrative, Luke takes these issues seriously, for they must be dealt with for the advance of the Christian message. He also provides numerous dynamics that are part of the process of resolving the conflict(s): sensitivity to the divine initiative, discernment of God’s saving activity, a commitment to the internal unity of the Church, various stories that are told in the process of resolving the conflict, the role of the Holy Spirit, importance of Scripture, decision with compromise, and the clear communication of the Council’s decision through a formal letter and supporting emissaries. These are not isolated “steps” but are interdependent aspects or important considerations in resolving this important conflict. The conflict resolution story in Acts 15 belongs to a coherent set of case studies in Acts in which the stories actually lead to an advance of the Christian message; the conflicts do not lead to the detriment or division of the Church.

The Jerusalem Council represents a great moment in salvation history. In the search for Gentile identity, the Jewish community rediscovers and redefines its own identity.89 Luke shifts from the threats or costs to both groups to the benefits for all Christian groups. Perhaps Luke might say to the Church, “When conflicts arise, do not avoid them, but welcome them and take them seriously. Look to the positive potential of resolving conflicts by which the Christian witness will advance through the inner and numerical growth of the Christian community.” Through the story, Luke invites his readers to experience and feel the various points of tension, to see how the conflict was managed and, indeed, advanced the Christian message—to be changed and then return to their own communities with this instructive paradigm. He helps the community to live and relive the event and its nuances and thereby, adopt and embrace his point of view in changing thoughts, attitudes, and behavior as to how the Church ought to discern the will of God in an ever-changing landscape. Even though Luke is irenic in his approach, he is honest enough to provide a discursive narrative about a critical situation, which desperately needs resolution if the Church is to achieve a unified, effective and Spirit-empowered witness (1:8).

About the Author

J. Lyle Story, Ph.D., is professor of Biblical languages and New Testament in the School of Divinity of Regent University and co-author of Greek to Me (Longwood FL: Xulon Press, 2002) and the Greek to Me Multimedia Tutorial, in addition to numerous journal and dictionary articles. Email: lylesto@regent.edu

References

1 Comparative analysis of the Western text with the Alexandrian text. Eldon Jay Epp, The Theological Tendency of Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis in Acts (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1966); B. D. Ehrman, “Textual Criticism of the New Testament,” in Hearing the New Testament, ed. Joel Green (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995), 127; F. S. Spencer, “Acts and Modern Literary Approaches,” in The Book of Acts in its First Century Settings, vol. 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1993), 410.

2 Richard I. Pervo, Acts (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2009); Clayton N. Jefford, “Tradition and Witness in Antioch: Acts 15 and Didache 6,” Perspectives in Religious Studies (1992): 409-419; Clayton N. Jefford, “An Ancient Witness to the Apostolic Decree of Acts 15?” Eastern Great Lakes Bible Society (1981): 204-213.

3 Ernst Haenchen, The Acts of the Apostles: A Commentary (Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1971).

4 David Trobisch, “The Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15 and Paul’s Letter to the Galatians,” Theological Exegesis (1999), 331-338; Hal Taussig, “Jerusalem as Occasion for Conversation: The Intersection of Acts 15 and Galatians 2,” Forum (New Series) 4, vol. 1 (Spring 2001): 89-104; F.F. Bruce, The Book of Acts (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1964), 298-302. For opposing views, see Richard I. Pervo, Profit with Delight (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987), 40-41 and Colin J. Hemer, The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History (Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1989), 269.

5 Gerd Lüdemann, Early Christianity According to the Traditions in Acts, trans. John Bowden (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1989).

6 Michael Enyinwa Okoronkwo, The Jerusalem Compromise as a Conflict–Resolution Model: A Rhetoric– Communicative Analysis of Acts 15 in the Light of Modern Linguistics (Bonn: Borengässer, 2001).

7 My purpose is not to reconstruct the historical events but to probe into the transformative value of the story and its appropriation by various faith-communities as they seek to discover God’s will in the midst of conflicts.

8 See Ez 5:5, 38:12; Is 2:1-3; Mi 4:1-2; Jub. 8:19; 1 En 26:1. Bauckham states, “It was entirely natural that the first Christian community, which saw itself as the nucleus of the renewed Israel under the rule of his Messiah and the leadership of its twelve phylarches, should have placed its headquarters in Jerusalem.” Richard Bauckham, The Book of Acts in its Palestinian Setting, vol. 4 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995), 422-423.

9 See Johannes Munck, Paul and the Salvation of Mankind (Richmond, VA: John Knox, 1959), 233-238, for analysis of Peter’s role within the book of Acts and Gal 2.

10 F.J. Foakes-Jackson, The Acts of the Apostles (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1960), 137.

11 These elders are to be contrasted with the unbelieving Jewish elders, used in pejorative contexts, often in tandem with chief priests (Acts 4:5, 8, 23; 6:12; 23:14; 24:1; 25:15).

12 James is noted as the brother of the Lord in Mk 6:3; Mt 13:55.

13 C. K. Barrett, Luke (ICC) vol. II (London: T & T Clark, 2002), 722. In Gal 1:19, James is noted as the “brother of the Lord” joined with the “pillars” (stu/loi in conjunction with Cephas and John) and “those who were reputable” (oi( dokou=ntev) in Gal 2:2, 6—twice, 9.

14 Joseph B. Tyson, “Themes at the Crossroads: Acts 15 in its Lukan Setting,” Forum (New Series) 4, vol. 1 (Spring 2008), 110.

15 Luke also informs the readers that the result of the persecution expanded the Christian witness, “those who had been scattered preached the word wherever they went” (Acts 8:4) and were accompanied by miraculous signs and exorcisms (Acts 8:5-8).

16 Acts 11:18, 22-24; 15:1-29; 18:22; 21:17-25. Charles H. Talbert, Reading Acts (New York: Crossroad, 1997), 136.

17 Hans Conzelmann, Acts of the Apostles, trans. James Limburg, Thomas Kraabel, and Donald H. Juel (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1987), 115. Minimized by Pervo, Acts, 368.

18 James D. G. Dunn, The Acts of the Apostles (Valley Forge, PA: Trinity, 1996), 195.

19 Otto Preisker, “ e!qov,” TDNT 2, 373.

20 Lk 1:9, 2:42, 22:39; Acts 6:14, 15:1, 16:21, 21:21, 25:16, 26:3, 28:17.

21 Alan Segal argues for a multiplicity of views within Judaism and more specifically Jewish Pharisaism with respect to the Gentile’s place in God’s scheme of things. “There is not a single answer . . . or policy on the status of the Gentiles.” Alan Segal, “Acts 15 as Jewish and Christian History,” Forum (New Series) 4, vol. 1 (Spring 2001), 64.

22 See also Ex 4:24-26; Jo 5:2-9; Lv 12:3; Acts 7:8. Texts such as Ex 12:48 provide provision for Gentiles becoming native Jews. Josephus’ Izates narrative (Ant. 20.34-38) is an interesting story that “depicts Izates’ progression from Gentile, to God-fearer, who kept all Jewish practices, except circumcision, to Jew—the status . . . of the approving narrator, allowed him only after circumcision.” Daniel R. Schwartz, God, Gentiles, and Jewish Law: On Acts 15 and Josephus’ Adiabene Narrative, Geschichte— Tradition—Reflexion (Tubingen: J C B Mohr, 1996), 26.

23 The book of Luke also contains a preponderance of the save word-family. While the OT emphasized that salvation means a rescue or victory from one’s enemies, Luke highlights the metaphorical use of salvation that is eschatological in nature.

24 Thus, many of the speeches in the book of Acts narrate the story of the Jesus-event (Acts 2:22-36, 3:12-26, 4:8-12, 10:34-43) with an aim of eliciting a trust–response from the listeners (e.g., “be saved from this corrupt generation,” 2:40). In 4:12, Peter makes it clear that salvation is only to be possessed in Jesus Christ of Nazareth, crucified but resurrected (= “the name”). Jesus is also the savior to whom God has exalted to his right hand (5:31).

25 The presence of salvation includes the response of repentance, the forgiveness of sins, and the gift of the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:38-40, 11:14-15), physical healing (Acts 4:9), personal joy and the joy of seeing others experiencing salvation (5:41, 8:39, 11:23, 13:48, 15:31), eternal life (13:48). See Graham H. Twelftree, People of the Spirit: Exploring Luke’s View of the Church (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2009), 46-47. Salvation is contingent upon a trust–response (16:31).

26 Texts such as Acts 2:20 speak of a future salvation, “And it shall be that whoever calls on the name of the Lord shall be saved.” There is a transposition from Yahweh to Jesus in the quote from Joel 2:32 to Acts 2:20. See also Acts 5:31; 13:23, 26. Many of the occurrences of the save word-family can embrace more than one aspect of salvation. While other similar texts may not explicitly use the save word-family, nonetheless they orient the community to the future with confident expectation: “repent turn to God, sins wiped out, times of refreshment may come from the Lord and that he may send the Christ . . . until the time comes for God to restore everything” (Acts 3:19-21).

27 Dunn, The Acts of the Apostles, 198.

28 Barrett, Luke, 698.

29 Walter Bauer, Frederick W. Danker, William F. Arndt, F. Wilbur Gingrich (hereinafter BDAG), A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1979), 542.

30 A favorite expression of Dunn, The Acts of the Apostles, 200.

31 Walter Gutbrod, “no/mov,” TDNT IV, 1066-67.

32 “turmoil” (Acts 19:40; 23:7,10; 24:5).

33 or “sharp dispute” (18:15, 23:29, 25:9, 26:3).

34 It appears that Luke has simplified the Jewish understanding of the Law as a “delight, privilege and joy” (e.g., Ps 119). See Barrett, Luke, 719, and Haenchen, The Acts of the Apostles, 429, which would characterize Luke’s time and environment. The pejorative sense of “yoke” and “burden” are clearly expressed in Mt 11:28-30, 23:4.

35 For the use of peira/zein as “to challenge” see Ex 17:2, Mt 4:7, and Lk 4:12 from Dt 6:16.

36 parenoxlei= “cause trouble, difficulty, annoy,” BDAG, 625. Aptly translated by Johnson as “harass.” Luke Timothy Johnson, The Acts of the Apostles (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical, 1992), 226.

37 Tyson, “Themes at the Crossroads,” 109.

38 God’s purposeful activity is also intimated in Acts 13:47 (Is 49:6), “I have made you a light for the Gentiles, that you may bring salvation to the ends of the earth.”

39 The verb with its negative, “he made no distinction” (ou0qe\n die/krinen) expresses the divine determination of the divine/human story of the former vision (Acts 10:9-16, 20; 11:2-17). Through the visionary-lesson, Peter interprets God’s decision.

40 An infinitive of purpose, again reinforcing the divine initiative and action.

41 The aorist infinitive “to be saved” (swqh=nai) may be rendered “we shall be saved” as a statement of purpose. Johnson, Acts of the Apostles, 263.

42 Ibid.

43 Luke’s summaries (2:42-47, 4:32-37, 5:12-16, 6:7, 12:24, 16:5, 19:20) often stress the numerical growth of added disciples (e.g., 3,000 in 2:41; “more and more men and women believed” in 5:14; “grew and multiplied” in 12:24). See Twelftree, People of the Spirit, 178.

44 Twelftree, People of the Spirit, 178.

45 A successful mission in Samaria (8:4-25) comes as a result of scattering, noted twice (8:1, 4).

46 A technical term of religious communities . . . fellowship, community, church. BDAG, 668.

47 However, there are two pejorative statements: (1) Peter’s rebuke of the hardliners, “Why do you challenge God?” in v. 10, 2 and the disavowal of the hardliners by James, “some went out from us without our authorization” in v. 24.

48 Rom 15:6 is the only other occurrence of the term in the NT.

49 Other uses of o(moqumado/n in Acts are in contexts of a united and aggressive front against Christians (e.g., 7:57).

50 Literally, “at one place,” BDAG, 288.

51 Tyson, “Themes at the Crossroads,” 109.

52 BDAG, 202. Admittedly the verb does not contain, “good” or “best,” but the context suggests the best approach.

53 Dunn, The Acts of the Apostles, 208.

54 See especially how Luke uses Is 49:6 in Acts 13:47 to argue for Gentile inclusion through Paul’s mission: “I have made you a light for the Gentiles, that you may bring salvation to the ends of the earth.”

55 Luke Timothy Johnson, Decision-Making in the Church (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1983), 80.

56 Conzelmann, Acts of the Apostles, 116.

57 “. . . by no means, no, certainly not” stating a negative reaction,” BDAG, 517.

58 Acts 1:14; Mk 6:3; Gal 1:19.

59 Also parallel with the aorist, “God chose” (e0cele/cato [v.7])

60 The clearest OT link is Zec 2:11 (2:15 in Heb), “many Gentiles . . . will become my people.”

61 Dunn, The Acts of the Apostles, 201.

62 Martin Dibelius, The Book of Acts, ed. K. C. Hanson (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress, 2004), 145.

63 The frequent word “power” (du/namiv) designates the same witness as “signs and wonders” and are often used in the same context (Acts 2:22, 3:12, 4:7, 4:33, 6:8, 8:13, 10:38, 19:11; “powerful” [du/natov] in 7:22)—in reference to Jesus and the early missionaries.