Authentic Leadership: Commitment to Supervisor, Follower Empowerment, and Procedural Justice Climate

This study examined the authentic leadership relationships with follower outcomes of commitment to supervisor and empowerment and the extent to which procedural justice moderated these relationships through quantitative methodology. The study utilized a cross sectional survey approach and convenient sampling (N=152). Theoretical framework underpinning the study is provided as well as tested hypotheses. Summary of results and limitations of this research are discussed.

Authenticity as first referenced in management and organizational literature viewed the authentic capacity of a leader as a litmus test of executive quality (Kluichnikov, 2011). With renewed interest in recent years on positive leadership (Luthans, 2002), there has been scholarly focus on the development of the authentic leadership construct (Luthans & Avolio, 2009; Walumbwa et al., 2010a). The core of authentic leadership extends beyond the authenticity of the leader as a person to encompass authentic relations with followers (Gardner et al., 2005; Avolio & Gardner, 2005). This relationship is characterized by: (a) transparency, openness and trust, (b) guidance toward worthy objectives, and (c) an emphasis on follower development (Gardner et al., 2005). Consequently, authentic leaders’ behaviors are reflected on the followers’ actions (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999; Fields, 2007; Zhu et al., 2011) and follower development (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999; Gardner et al, 2005; Walumbwa et al., 2010a).

The role of followership in leadership outcomes has been duly documented in the literature (Yukl, 2010; Hickam, 2010; Gardner et al., 2005; Fields, 2007; Zhu et al., 2011). For authentic leadership, Gardener et al. (2005) asserted that followership is an integral part of authentic leadership and authentic followers are expected to replicate authentic leader development (Gardner et al., 2005). Consequently, as positive role models, authentic leaders “serve as a key input for the development of authentic followers” (p. 347). To progress authentic leadership theory development, scholarly studies have investigated a number of relational outcomes of authentic leadership on followers (Gardner et al, 2011) that include (a) follower job satisfaction (Avolio, Gardner et al., 2004) and (b) Job performance (Chan et al., 2005; Luthans et al., 2005, Illies et al., 2005) and (c) empowerment, Walumbuwa et al., (2010a). Gardner et al. (2011), in a comprehensive review of authentic leadership development and studies, called for more empirical investigations of the role of followers, various antecedents and outcomes in authentic relationship, specifically, for further research that examines what components and situations develop a deeper understanding of the authentic leader follower relationships (Gardner et al., 2011).

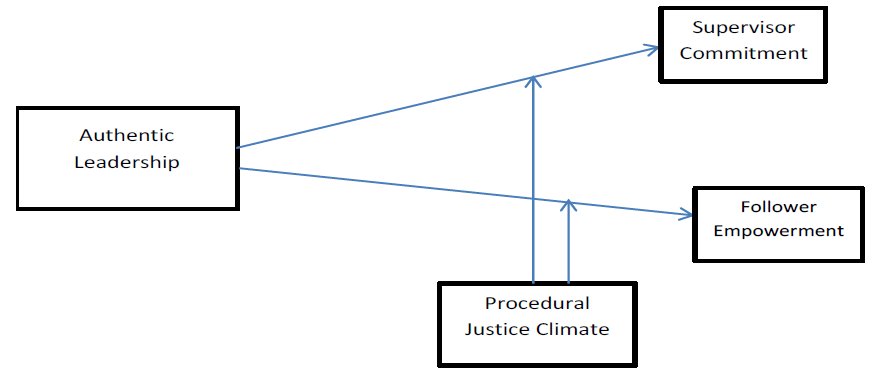

To heed the aforementioned call, this study examined (a) the relationship between authentic leadership and follower empowerment, and (b) the relationship between authentic leadership and follower commitment to supervisor. Further, this study investigated to what extent procedural justice as a perception of work climate moderates the AL relationship with both outcomes. Empowerment is generally accepted as in indicator that followers are trusted and capable (Walumbwa et al, 2010a). This derives from the conceptualization of empowerment as a psychological state that encompasses four cognitions, impact, influence, meaningfulness and self-determination (Speitzer, 2005) and commitment to supervisor indicates that the followers trust the supervisor to guide them and also an indicator of follower’s openness to supervisor’s influence (Illies et al., 2005) making these two outcomes important predictors of follower development. Consequently, findings from this study have implications for authentic leader-follower relationship development and will further aid understanding of the organizational climatic conditions that can enhance authentic leadership perception by followers in organizations.

Authentic Leadership and Related Leadership Theories

Authentic leadership has been described in self- referent terms (Fields, 2007; Gardner et al., 2005), Self-reflective (Fields, 2007; Avolio & Gardner, 2005) and as a root concept for positive leadership approaches such as charismatic, transformational and ethical leadership (Gardner et al., 2005; Walumbwa et al., 2010). Drawing on positive psychology, Gardner et al. (2005) advanced a self-based model of authentic leadership and follower development defining authenticity as being true to oneself – owning one’s experiences (values, thoughts, emotions and beliefs and “acting in accordance with one’s true self” (p. 344). The central premise of this model is that through increased selfawareness, self-regulation, (Sparrowe, 2005) and positive modeling, authentic leaders foster the development of authentic followers (Avolio & Gardner, 2005, Gardner et al., 2005). Self-awareness means leaders know what is important to them (May et al., 2003, Kluichnikov, 2011) and Sparrowe (2005) observed that self-regulation helps to facilitate transparency and consistency a leader’s behavior. Primarily, authentic leadership represents the root construct for what constitutes other forms of positive leadership (Gardner et al., 2005). Positive leadership refer to the activation of a set of cognitions, affects, expectancies, goals, values and self-regulatory plans that both enable and direct effective leadership (Hannah, Woolfolk & Lord, 2009). Positive leadership behaviors elicit responses from followers which feedback to further enhance the positive selfconcepts of both leaders and followers (Hannah et al., 2009).

Authenticity is premised on understanding and being true to one’s self (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; George 2003). Authentic leaders are believed to be deeply aware of their values, beliefs, are self-confident, perceived to be genuine, reliable, trustworthy and of high moral character (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Ilies, Morgeson & Nahrgang, 2005; Fields, 2007). Sparrowe (2005) links this awareness to self-regulation and a broader exploration of the self-regulation construct shows that it helps leaders weigh the gaps that may exist between their internalized standards and their praxis (Kluichnikov, 2011; Avolio & Gardner, 2005). The process of self-regulation is said to help the leader withstand external pressure and influence (Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Ilies, Morgeson & Nahrgang, 2005) increasing the authentic leader’s moral strength.

Authentic literature reviews indicated that the definition of the authentic leadership construct has converged around four underlying dimensions (Walumbwa et al., (2008) reflecting both conceptual and empirical composition (Gardner et al., 2011). These are: (a) balanced processing – a renaming of unbiased processing (Gardner et al., 2011), (b) internalized moral perspective, (c) relational transparency, and (d) self- awareness. Balanced/unbiased processing refers to the ability to objectively analyze and consider all information prior to decision making including contrary views. Internalized morality refers to the leader’s action being guided by deep rooted moral values and standards and not tossed by external pressures (peers, organizational and societal). Relational transparency involves personal disclosures, openly sharing information and expressing true thoughts and motives while self-awareness refers to leaders’ self -knowledge of their internal referent (mental states) and external referent (reflected self-image or how a leader is perceived) (Walumbwa et al., 2010; Gardner et al. 2005; Ilies et al., 2005; May, Chan, Hodges & Avolio, 2003). These related and substantive dimensions are all believed to be necessary for an individual to be considered an authentic leader.

As stated earlier, a number of authentic leadership relational outcomes have received empirical attention. Specifically, AL has been shown to be positively related to personal identification, positive leader modeling, follower job satisfaction, trust in leadership, organizational commitment follower work engagement, follower work happiness and follower job performance among others (Gardner et al., 2011). Altogether, “the available findings from quantitative studies provide support for the predictions advanced by and derived from AL theory” (P. 1139). Therefore, Gardner et al. (2011) assert that nomological network of constructs empirically associated with AL is generally consistent with the extended theoretical framework.

Hypothesized Theoretical Model

Authentic Leadership and Follower Commitment to Supervisor

Work experiences including supervisory conditions can have a strong influence on the extent of psychological attachments that are formed in organizations (Dale & Fox, 2008). Supervisory conditions refer to the degree to which a leader/supervisor created a climate of psychological support, mutual trust, respect, and helpfulness. Positive modeling is key role in the formation of authentic relationships between leaders and followers (Gardener et al., 2005). Walumbwa et al. (2010a) examining the links between authentic leadership and OCB posited that authentic leaders, through their ethical role modeling, transparency, and balanced decision-making, create conditions that promote positive extra-role behaviors from followers. Authentic leaders displaying relational transparency are focused on building followers’ strengths, enlarging their thinking, creating a positive, balanced and engaging organizational context (Ilies et al, 2005; Avolio & Gardner, 2005; Walumbwa et al., 2010a), a context which no doubt, provides follower desired climate of psychological support, mutual trust and helpfulness necessary for follower commitment (Dale & Fox, 2008). Furthermore, AL relational transparency operates from the root of relationship theory which is the same domain of affective commitment (Walumbwa et al., 2010). Affective commitment is defined as emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement in the organization (Meyer & Allen, 1991). Macy and Schneider (2008) opined that employee engagement treated as a state could mean attachment, involvement and commitment) and Walumbwa et al, (2010a) found authentic leadership to be positively related to workplace engagement. Employee engagement as used here refers to the individual’s involvement and satisfaction with work as well as enthusiasm for work. Gardner, et al. (2005) argued that followers readily embrace a leader who displays candor, integrity and a developmental focus (as modeled by authentic leaders) to build a long and productive career. By setting a personal example of high moral standards of integrity, authentic leaders are expected to evoke a deeper sense of personal commitment among followers (Walumbwa et al., 2008) and in the process, elevate follower self-awareness.

In consideration of the above therefore,

Hypothesis 1: Authentic leadership is positively related to follower commitment to supervisor.

Authentic Leadership and Follower Empowerment

The theoretical work on authentic leadership has described authentic leaders as having followers who increasingly identify with and feel more psychologically empowered to take on greater ownership for their work (Ilies et al, 2005, Walumbwa et al., 2010a). The empowerment construct has been conceptualized as increased intrinsic task motivation which manifests in these four cognitions reflecting an individual’s orientation to work role: (a) competence , an individual’s belief in his or her capability to be effective, (b) impact, the extent to which an individual can influence strategic, operational and administrative outcomes in a work environment, (c) meaning, the value of work goal or purpose, judged in relation to an individual’s own ideals or standard, and (d) self-determination, an individual’s sense of having a choice in initiating and regulating actions. Follower developmental process is an integral part of authentic leadership and through positive modeling and direct communications, authentic leaders can help followers achieve authenticity and self-concordant identities Gardener et al. 2005). In this relationship, “followers’ needs for competence and autonomy can be met by helping them discover their talents, develop them into strengths and empowering them to do tasks for which they have capacity to excel” (p. 364).

Empowerment is characterized by autonomy. Self-determination reflects autonomy (Sprietzer, 1995; Walumbwa et al., 2010a). Authentic leaders support self-determination of followers, by providing opportunities for skill development and autonomy and through social exchanges, authentic leaders influence and elevate followers (Ilies et al., 2005). As Gardner et al argued, authentic leaders are expected to facilitate the experience of engagement by helping followers discover for themselves their true talents and to facilitate the use of those talents, “helping them to create a better fit between work roles and salient self-goals of authentic self” (p. 366). This in turn contributes to sustained veritable individual and organization performance. Walumbwa et al. (2010a) reported that followers of managers who promoted a more inclusive work climate and readily shared information, both of which are behavioral characteristics of authentic leaders, reported higher levels of psychological empowerment. Through their internalized moral perspectives and balanced processing, authentic leaders provide higher levels of feedback to their followers.

One way to motivate employees is with a sense of purpose to deliver sustained superior services, innovative and quality products (Walumbwa et al., 2008). Authentic leaders are more interested in fostering high-quality relationships based on the principles of social exchange rather than economic exchange (Ilies et al., 2005; Walumbwa et al., 2008). From the social exchange perspective, followers of authentic leaders are expected to be willing to put in extra effort into their work to reciprocate the highly valued relationship with their leaders. Feelings of empowerment have been positively related to organizational citizenship behavior (Walumbwa et al., 2010a) where individuals “perceive more of a line of sight between their actions and broader unit outcomes” (p. 905) in addition to feeling more responsibility for helping beyond their job responsibilities. Organizational citizenship behavior has been reported to be positively related to authentic leadership (Walumbwa et al., 2008; Gardner et al., 2011).

Furthermore, relational transparency means the authentic leader displays high levels of openness, and trust in close relationships with followers. Empowerment is a direct effect of supervisors trusting followers. By promoting and building transparent relationships, more rapid and accurate transfer of information occurs and this facilitates more effective follower performance (Walumbwa et al., 2008). Evidently, relational transparency drives follower empowerment because when the supervisor is transparent, he/she will let the follower know correct behaviors and task directions and therefore empower the followers to action and performance. Given the above premise, authentic leadership should positively relate to follower empowerment.

Hypothesis 2: Authentic leadership is positively related to follower perceived empowerment.

Procedural Justice Climate as a Moderator of Supervisor Commitment and Follower Empowerment in AL

Procedural justice climate is defined as “distinct group-level cognition about how work group as a whole is treated” (Naumann & Bennett, 2000, p. 882), although procedural justice has mainly been conceptualized as an individual-level phenomenon based on self-interest and implying “that which is fair is that which benefits all” (p. 881), climate perceptions represent meaning derived from the organizational context and they form the basis for individual and collective responses (Naumann & Bennet, 2000). According to Gardner et al. (2005), ‘structural theory of organizational behavior and an inclusive structure, provides a theoretical basis for examining a relationship between authentic leadership and followership and the organizational climate” (p. 367). Three important conditions underpin procedural justice perceptions (Walumbwa et al., 2010b), these are the extent to which the process (a) is moral and ethical, (b) consistently applied, and (c) provides equal opportunity for all employees to speak and influence the outcome. Considering the dimensions of authentic leadership – internalized moral perspective (acting ethically and with integrity at all times), relational transparency (openly sharing information), balanced processing (including others views) and self-awareness (knowing one’s mental state and concern for follower perception) of authentic leadership, it is expected that procedural justice climate will enhance the relationship between AL and follower outcomes. It is also expected that procedural justice will moderate this relationship because in order to elicit positive follower outcomes. Gardner et al. (2005) described authentic leadership work climates that provide full access to information, resources, and support as well as opportunities to learn and develop procedures that are structurally and interactionally fair.

Procedural justice is a signal that the leader is generally fair and acts with integrity (Dirks & Ferrin, 2002). Given that authentic leaders are primarily driven by internalized regulatory processes and are characterized with high-level of moral identity (Zhu et al., 2011), they are obliged to maintain a consistency between what they do, what they believe, and what they should do. These behaviors and mechanisms exhibited by authentic leaders, lend themselves to be positively influenced by procedural justice climate since procedural justice alludes to equity and fair play. Walumbwa et al (2010b) asserted that fair procedures signal to employees that they are valued (Walumbwa et al., 2010b).

Avolio and Gardner (2005) proposed that environments that provide open access to information, resources, support, and equal opportunity for everyone to learn and develop will empower and enable leaders and their associates to accomplish their work more effectively. Accordingly, a leader’s authenticity and integrity must be recognizable by followers in order for these positive personal attributes to make a difference in the degree or nature of the leader’s influence (Fields, 2007). The implication for the development of authentic leader-member relationships “in unconstrained settings is that followers and leaders will be most likely to form trusting and close relationships” (Gardner et al., 2010) with persons who see their true selves producing interpersonal feelings of justification. In addition, Ehrhart (2004) reported that fair leadership results in higher perceptions of procedural and distributive justice, that higher LMX are positively related to subordinate perceptions of supervisor fairness. Therefore, a fair and equitable context enhances authentic leadership given that the authentic leader exhibits transparency and is unbiased in decisions and treatment of followers. Given the above, this research tests the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3a: Procedural justice moderates authentic leadership-commitment to supervisor relationship so that the effects of AL on commitment are greater when procedural justice climate is rated higher.

Hypothesis 3b: Procedural justice moderates authentic leadership-follower perceived empowerment relationship so that the effects of AL on follower perceived empowerment are greater when procedural justice climate is rated higher.

Methods and Procedures

Research Design

The following variables are identified in the study: (a) Independent variable – authentic leadership, (b) dependent variables – commitment and empowerment, and (c) moderating variable – procedural justice climate. Measures of control for this study include followers’ age, gender, and tenure.

Participants

Use of questionnaires was the preferred data collection procedure for this study because of the economy of the design and the rapid turnaround data collection required for this study. A stratified random sampling (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000) was preferred, however, great difficulty was experienced in getting data as there was great reluctance by Nigerians in employment to complete questionnaires. Consequently, the study adopted a convenience sampling strategy. Convenient sampling allows the researcher to draw a sample from the larger population, which is readily available and convenient (Harrison, 2011). Sample of 20 respondent per independent variable has been suggested (Girden, 2001; Hair et al., 2011) and for this study 200 questionnaires were given out and a total of 168 respondents returned completed questionnaires yielding a response rate of 84%. Out of the 168 returned, 16 had missing data and were not used in the study. Total usable responses were 152. Respondents represent employees across sectors including banking (approximately 80%), education (5%), oil & gas (10%) and services industries (5%).

Measures

Previously validated instruments used in peer reviewed journals were utilized for this study. The authentic leadership questionnaire (ALQ) (Walumbwa et al., 2008) – a 16 items scale, was used to measure authentic leadership perception. The 16 items were used in this study and reliability was .78. Sample question include “My leader encourages everyone to speak their mind.”

Parker, Baltes, and Christiansen’s (1997) instrument was used to measure procedural justice climate, a 4-item scale that assesses employee perceptions of the extent to which employees have input and involvement in decisions as indicator for both voice and choice. The measure assesses judgments about the overall organization instead of policies or practices in a specific area (Fields, 2002). The 4-item scale was used in this study with reliability alpha of .75.

Commitment to supervisor was measured with Becker, Billings, Eveleth, and Gilbert’s (1996), 4-item scale for supervisor–related internalization was used for this study with reliability alpha of .78.

Spreitzer’s (1995) empowerment at work instrument was used to measure perceived empowerment. The scale has four dimensions: (a) competence (3 items), (b) impact (3 items), meaningfulness (3 items), and (d) self-determination (3 items). Sample item is “I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job.” Although the 12 items were used in the data collection, only 11 items were used in the analysis as one dimension with a coefficient alpha of .82. These four measures were combined into one instrument of 36 item questions for ease of data collection, reducing multiple questionnaire completion by participants which can cause weariness and loss of interest. Unless otherwise indicated, all measures were answered on a 5-point Likert scale (1= strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). (See appendix A)

Prior to data analysis, all measures used in this study were tested for reliability within the sample and all of them returned a reliability threshold of > .6 (see Table 1 for details)

Table 1: Chronbach’s alpha for instruments used in the study

| Instrument | Chronbach alpha | Number of items in the scale |

| Authentic Leadership | 0.77 | 16 |

| Procedural Justice | 0.75 | 4 |

| Commitment to Supervisor | 0.78 | 4 |

| Empowerment | 0.81 | 11 |

Procedure

Data obtained from the survey instruments were entered into Statistical package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software (version 19.0). Inferential statistics, specifically multiple linear regression analyses were used to test the level of support for each hypothesis. According to Williams (1992), multiple regression can be used as a method of describing the relative degree of contribution of a series of variables in the multiple prediction of a variable. Also, categorical variables: age, gender and tenure were introduced as predictors in multiple regression equations.

Results

Prior to conducting the regression analyses, correlations between the variables were examined. The results of Pearson r correlation are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Correlations between variables

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1. Comm. to supervisor | 3.41 | 0.85 | – | ||||||

| 2. Empowerment | 3.96 | 0.51 | .29** | – | |||||

| 3. Authentic leadership | 3.75 | 0.79 | .46** | .21** | – | ||||

| 4. Procedural justice | 3.5 | 0.78 | .33** | .25** | .26** | – | |||

| 5. Age | 34.33 | 7.61 | -0.08 | 0.03 | -0.14 | -0.13 | – | ||

| 6. Sex | 1.52 | 0.53 | 0 | 0.08 | -0.07 | -0.02 | -0.14 | – | |

| 7. Tenure | 2.56 | 2.64 | -0.14 | -0.01 | -.25** | -0.17 | .32** | -.10 | – |

The dependent variables, commitment to supervisor and empowerment were found to be positively correlated with authentic leadership behaviors. Procedural justice was positively correlated to dependent variables empowerment and commitment to supervisor and authentic leadership. While authentic leadership had the strongest positive correlation with commitment to supervisor, tenure showed the strongest negative correlation with authentic leadership. In addition, age was positively correlated with tenure. The coefficients for authentic leadership, sex, and commitment to supervisor statistically significant in the model.

The first hypothesis suggested that authentic leadership behaviors will lead to commitment to supervisor. To test this relationship, authentic leadership was entered as the independent variable and commitment to supervisor as dependent variable. All control variables (age, sex, and tenure) were entered as independent variables (see Table 3 for detailed beta values).

The model accounted for 21.6% of variance in commitment to supervisor. The regression model is significant. With Authentic leadership, there was a variance increase of 19.5%. The standardized coefficient showed authentic leadership had a significant influence on commitment to supervisor. Standardized coefficient beta is .46.

P value = .004 < 05. Therefore, H1 is supported.

Table 3

Linear Regression for H1 : Dependent Variable = Commitment to supervisor.

Significant coefficient t (147) = 6.0, p < .05

| Variable | Model 1beta | Model 2 beta |

| Authentic leadership | 0.49 | |

| Age | 0 | 0 |

| Sex | -0.02 | 0.06 |

| Tenure | -0.04 | 0 |

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| ∆R2 | 0.02 | 0.2 |

| Df1 | 3 | 1 |

| Df2 | 148 | 147 |

| F for change | 1.06 | 36.48 |

| Sig F change | 0.37 | 0 |

The second hypothesis states that authentic leadership behavior can predict employee empowerment outcome. In this regression all control variables were entered in block 1 as independent variables (see Table 4 for detailed beta values).

Table 4

Linear Regression for H2: Dependent variable = Empowerment.

| Variable | Model 1beta | Model 2 beta |

| Authentic leadership | 0.16 | |

| Age | 0 | 0 |

| Sex | -0.08 | 0.11 |

| Tenure | 0 | 1 |

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| ∆R2 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Df1 | 3 | 1 |

| Df2 | 148 | 147 |

| F for change | 0.48 | 8.61 |

| Sig f change | .69 | .00 |

Control variables accounted for just 1% variance in the model. Authentic leadership increased the variance by .055 (5.5%). R2 without authentic leadership = 0.01 and R2 with authentic leadership = 0.06. Authentic leadership is positively related to empowerment. p = .004 < .05, which means the model is significant and H2 is supported. The R2 change was also significant (∆R2 = .195, F(4,147) = 10.10, p<.05.

The first part of hypothesis 3 states that procedural justice moderates authentic leadership-commitment to supervisor relationship so that the effects of AL on commitment to supervisor are greater when procedural justice climate is rated higher. During this regression, a variable modeling the interaction of authentic leadership and procedural justices (INTPJAL2) was computed. Authentic leadership and procedural justices were entered as IV in block1 without the control variables and commitment to supervisor (Comsupervisor) as DV. The newly computed INTPJAL2 was entered as independent in block 2 of 2 (see table 5 for detailed beta values).

Table 5

Multiple Linear Regression for H3a : DV = commitment to supervisor. Moderating variable = procedural justice.

Variable Model 1 beta Model 2 beta

| Variable | Model 1 beta | Model 2 beta |

| Procedural justice | 0.24 | 0.58 |

| Authentic leadership | 0.43 | 0.77 |

| INTPJAL2 | -0.09 | |

| R2 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| ΔR2 | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| Df1 | 2 | 1 |

| Df2 | 149 | 148 |

| F change | 26.44 | 0.93 |

| Sig f change | 0 | 0.34 |

The above table shows the influence of authentic leadership on commitment to supervisor and the moderating effect of procedural justice. R2 = .005 which means that less than 1% variance is accounted for in the in the model. The p value = .337 > .05 which means that hypothesis 3A is not supported. Therefore, the regression model is not significant.

Hypothesis 3b states that procedural justice moderates authentic leadership-follower perceived empowerment relationship so that the effects of AL on follower perceived empowerment are greater when procedural justice climate is rated higher. During this regression, a variable modeling the interaction of authentic leadership and procedural justices (INTPJAL2) was computed. Authentic leadership and procedural justices were entered as IV in block1 and excluding all control variables and empowerment as DV. The newly computed INTPJAL2 was entered as independent in block 2 of 2 (see table 6 for detailed beta values).

Table 6

Multiple Linear Regression for H3b: DV = empowerment and moderating variable = procedural justice

| Variable | Model 1 beta | Model 2 beta |

| Procedural justice | 0.14 | 0.54 |

| Authentic leadership | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| INTPJAL2 | -0.11 | |

| R2 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| ΔR2 | 0.1 | 0.02 |

| Df1 | 2 | 1 |

| Df2 | 149 | 148 |

| F change | 7.13 | 2.9 |

| Sig F change | 0 | 0.09 |

R2 = .018 indicating that 1.8% of the variance accounted for by the regression model. Statistical significance = .091 > .05, H3b is supported and model is significant. In field studies .10 is an acceptable level in moderation effect. McClelland and Judd (1993) stated that when reliable moderator effects are present, the reduction in model error due to adding the product term “is disconcertingly low” (p. 377) therefore effects as little as 1% of the total variance should be considered important.

Discussion

This study was motivated by a desire to investigate and understand relationship between authentic leadership and employee outcomes. The study used regression analysis to determine the relationships of authentic leaderships with commitment to supervisor and empowerment as well the moderating effect of procedural justice in both relationships. Hypothesis 1 and 2 were supported in this study indicating that authentic leadership as a positive form of leadership influence employee outcome across cultures. The predicted outcome of positive relationship between authentic empowerment and commitment to supervisor is a clear indication that relational transparency, balanced processing are leadership behaviors that affect follower/employee development. The unsupported moderating effect of procedural justice on authentic leadership and commitment to supervisor is believed to be a result of followers’ perception of procedural justice to be inherent in fair leadership that resonates with authentic leaders. Ehrhart (2004) reported that perception of fair leadership results in higher perceptions of procedural and distributive justice. The opportunity to carry out this study in Nigeria, richly adds to the cross cultural application of authentic leadership in addition. Generally, the results indicate that the more leaders exhibit authentic leadership behaviors, the more employees identify with such leaders.

This study has organizational leadership implications. First, the results indicate that it is beneficial for managers and organizational leaders to emphasize transparency, balanced processing and self-awareness which enhances commitment and employees are empowered to achieve more. Consequently, organizational willingness and readiness to develop authentic leaders will see increased productivity from empowered and committed employees, reduced attrition and turnover costs as well as sustained innovation resulting from continuity and commitment.

Limitations and Future Research

As with any research design, this study has some limitations. First, convenient sampling was used for this study which can raise questions about generalizability. Creswell (2009) cautions on the use of convenient sampling noting that it can limit the generalizability and compromise the representativeness of the sample population. Second, employee attitudes, perceptions, authentic leadership, and procedural climate ratings are supplied by the employees (all measures by questionnaire), this could open the study to possible common-method bias. Third, there is possibility of cultural interference. Nigeria is characterized as a high power culture (Hosftede, 2001) and this could impact generalizability. Walumbwa et al. (2010a) reported that employees in high power distance cultures are more likely to maintain a formal relationship with the leader that could limit their meaningful interactions with authentic leaders. As a result, authentic leadership could have minimized influence on follower outcomes. This could possibly explain why tenure had strong negative correlation with authentic leadership. One would have expected that the longer an employee is exposed to authentic leadership behavior, the more similar they become but the outcome of this research points to the contrary.

Given the limitations outlined above, future research should aim to utilize a stratified sample methodology. Future research may also focus on other psychological processes linking authentic leadership to follower behaviors such as work engagement and organizational citizenship behaviors. This will further strengthen the authentic leaderfollower outcome necessary for theory development. Considering that authentic leadership is centrally based on self-awareness and have individual consideration for ethics and culture, future studies should investigate these same outcomes in another culture as possible interference has already been noted and according to Hosfstede (2001) different cultures exhibit different values and values are central to authentic leadership behaviors.

About the Author

Amara Emuwa is a Ph.D. student of entrepreneurial leadership at the Regent University school of Business and Leadership. Correspondence regarding this article should be addressed to Amara Emuwa.

Email: amaremu@mail.regent.edu

References

Avolio, B. J., Gardner,W. L.,Walumbwa, F. O., Luthans, F., & May, D. R. (2004). Unlocking the mask: A look at the process by which authentic leaders impact follower attitudes and behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 15, 801−823.

Avolio, B. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2005). Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16, 315-338. Retrieved from www.sciencedirect.com

Bass, B., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181-217. Elsevier. Retrieved from http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1048984399000168

Castillo, J. J. (2009). Convenience sampling. Retrieved June 27, 2010 from Experiment Resources: http://www.experiment-resources.com/convenience-sampling.html

Clapp-Smith, R., Vogelgesang, G. R., & Avey, J. B. (2009). Authentic leadership and positive psychological capital: The mediating role of trust at the group level of analysis. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 15, 227–240

De Cremer, D., Dijke van, M., & Bos, A. E. R. (2006). Leader’s procedural justice affecting identification and trust. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 27(7), 554-565.

Diddams, M., & Chang, G.C. (2012). Only human: Exploring the nature of weakness in authentic leadership, The Leadership Quarterly (2012), doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.12.010.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002) Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87( 4), 611– 628.

Ehrhart, M. G. (2004). Leadership and procedural justice climate as antecedents of unitlevel organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 57, 61–94.

Fields, D. L. (2002). Taking the measure of work: A guide to validated scales for organizational research and diagnosis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fields, D. L. (2007). Determinants of follower perceptions of a leader’s authenticity andintegrity. European Management Journal, 25, 195–206.

Gardner, W. L., & Schermerhorn, J. R., Jr. (2004). Unleashing individual potential: Performance gains through positive organizational behavior and authentic leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 33, 270–281.

Gardner, W. L., Avolio, B. J., Luthans, F., May, D. R., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2005). Can you see the real me? A self-based model of authentic leader and follower development. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 343-372.

Gardner, W. L., Cogliser, C. C., Davis, K. M., & Dickens, M. P. (2011). Authentic Leadership: A review of the literature and research agenda. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 1120-1145.

Hannah, S. T., Woolfolk, R. L., & Lord, R. G. (2009). Leader self-structure: a framework for positive leadership. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(2), 269-290.

Harms, P. D., Spain, S. M., & Hannah, S. T. (2011). Leader development and the dark side of personality. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 495-509.

Hassan, A., & Ahmed, F. (2011). Authentic leadership, trust and work engagement. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences, 6(3), 164-171.

Henderson, J. E., & Hoy, W. K. (1983). Leader authenticity: The development and test of an operational measure. Educational and Psychological Research, 3(2), 63–75.

Hickman, G. R. (2010). Leading Organizations: Perspectives for a New Era (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G. H. (2001). Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Kerlinger, F. N., & Lee, H. B. (2000). Foundations of behavioral research (4 ed.). Orlando, FL: Harcourt College Publishers.

Kliuchnikov, A. (2011). Leader’s authenticity influence on followers’ organizational commitment. Emerging Leadership Journeys, 4(1), 70-90.

Lok, P., Crawford, J. (2001). Antecedents of organizational commitment and the mediating role of job satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 16(8), 594 – 613.

McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114(2) 376-390

May, D. R., Chan, A., Hodges, T., & Avolio, B. J. (2003). Developing the moral component of authentic leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 32, 247–260.

Macy, W. H., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1, 3-30.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resources Management Review, 1(1), 61-89.

Naumann, S. E., & Bennett, N. (2000). A case for procedural justice climate: Development and test of a multilevel model. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 881–889.

Price, T. L., (2003). The ethics of authentic transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 14, 67–81

Salkind, N. J. (2011). Statistics for people who (think they) hate statistics (4th ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Sekeranm U. (2000). Research methods for business: A skill building approach (3rd ed.) New York:Wiley

Sprietzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the work place: Dimensions, measures and validations. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 1442-1465.

Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34, 89–126.

Walumbwa, F. O., Wang, P., Wang, H., Schaubroeck, J., & Avolio, B. J. (2010a). Psychological processes linking authentic leadership to follower behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 21, 901–914.

Walumbwa, F. O., Hartnell, C. A., & Oke, A. (2010b). Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-level investigation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(3), 517-529.

Williams, F. (1992). Reasoning with statistics: How to read quantitative research (4th ed.). Oralndo, Fla: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Yammarino, F. J., Dionne, S. D., Schriesheim, C. A., & Dansereau, F. (2008). Authentic leadership and positive organizational behavior: A meso, multi-level perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 19, 693–707.

Yukl, G. (2010). Leadership in organizations (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Zhu, W., May, D. R., & Avolio, B. J. (2004). The impact of ethical leadership behavior on employee outcomes: The roles of psychological empowerment and authenticity. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 11, 16–26.

Zhu, W., Avolio, B. J., Riggio, R. E., & Sosik, J. J. (2011). The effects of authentic transformational leadership on follower and group ethics. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 801-817.

Appendix

Questionnaire Sample Items

June 2012

Confidential Research Survey

About You: (a) Age …….. (b) Sex …….. (c) Tenure with current manager …….

Questionnaire completion Instructions: Please circle the right answer. Please answer all questions.

Responses for this section: (1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neutral (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree My Leader:

Responses for this section: (1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neutral (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree

My Leader:

- says exactly what he or she means 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- demonstrates beliefs that is consistent with action 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- shows he or she understands how specific actions impact others 1 2 3 4 5

The following statements describe your perception of decision making in the organization

- people involved in implementing decisions have a say in making the decisions 1 2 3 4 5

- members of my work unit are involved in making decisions that directly affect their work 1 2 3 4 5

- Decisions are made on the basis of research, data, and technical criteria, as opposed to political concerns 1 2 3 4 5

- People with the most knowledge are involved in the resolution of problems 1 2 3 4 5

- If the values of my supervisor were different, I would not be as attached to my supervisor 1 2 3 4 5

The following statements describe perceived commitment to your manager/leader.

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neutral (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree

- says exactly what he or she means 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- demonstrates beliefs that is consistent with action 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- ———- 1 2 3 4 5

- shows he or she understands how specific actions impact others 1 2 3 4 5

The following statements describe your perception of decision making in the organization

- people involved in implementing decisions have a say in making the decisions 1 2 3 4 5

- members of my work unit are involved in making decisions that directly affect their work 1 2 3 4 5

- Decisions are made on the basis of research, data, and technical criteria, as opposed to

political concerns 1 2 3 4 5 - People with the most knowledge are involved in the resolution of problems 1 2 3 4 5

The following statements describe perceived commitment to your manager/leader.

(1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neutral (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree

- If the values of my supervisor were different, I would not be as attached to my supervisor

1 2 3 4 5 - My attachment to my supervisor is primarily based on the similarity of my values and those represented by my supervisor 1 2 3 4 5

- Since starting this job, my personal values and those of my supervisor have become more

similar 1 2 3 4 5 - The reason I prefer my supervisor to others is because of what he or she stands for, that is, his or her values 1 2 3 4 5

The following statements relate to your perceptions of your job.

Responses for this section (1) Strongly disagree (2) Disagree (3) Neutral (4) Agree (5) Strongly agree

- The work I do is very important to me 1 2 3 4 5

- My job activities are personally meaningful to me 1 2 3 4 5

- The work I do is meaningful to me 1 2 3 4 5

- I am confident about my ability to do my job 1 2 3 4 5

- I am self-assured about my capabilities to perform my work activities 1 2 3 4 5

- I have mastered the skills necessary for my job 1 2 3 4 5

- I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job 1 2 3 4 5

- I can decide on my own how to go about doing my work 1 2 3 4 5

- I have considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do my job

1 2 3 4 5 - My impact on what happens in my department is large 1 2 3 4 5

- I have a great deal of control over what happens in my department 1 2 3 4 5

- I have significant influence over what happens in my department 1 2 3 4 5